Book of Stolen Tales (23 page)

Read Book of Stolen Tales Online

Authors: D J Mcintosh

The night was cool enough that I buttoned up my jacket. Out there, without the interference of city lights, in the clear Provençal air and the landscape flat to the horizon, the sky was a vast indigo plain. The great band of stars in the Milky Way stood out like a dust shower of diamonds. Silhouettes of the sheep and white horses were visible as they stood on the grass.

One of the horses lifted its head and whinnied and I felt an unexplainable jolt of fear. The horses moved closer together, as if in a tight group they could better defend themselves. The sheep huddled in the same way. A cluster of fireflies burst up suddenly from the grass and scattered.

Something had disrupted the tranquil pastoral night. I concentrated hard to detect it. I could hear something moving along the rough ground. A swishing sound, barely perceptible. A black cloud sailed across the moon. I peered in the direction of the sound but the gloom prevented me from seeing anything.

My brother, Samuel, was a scholar of ancient cultures and not given to flights of fancy. A brilliant man who pursued his studies rigorously, he was also open-minded. I'd been thinking about him a lot, especially since Dina had told me about Mancini's interest in necromancy. What would Samuel have thought? The answer came rushing to me then, under the stars, on the edge of this great plain. Once, when I asked him about Babylonian beliefs, he'd said, “Their old gods aren't dead, you know. They've just withdrawn to hidden places.” He smiled then as if to make light of it all. “Perhaps I've been spending too much time studying Mesopotamians. And yet on occasion when I'm in remote landscapes where the arid desert seems endless, I sense their presence. They are neither evil nor good and are driven by urges and desires we cannot comprehend. We Westerners like to think our spiritual allies are caught up in our lives, whether to save us or wreak vengeance on us for our sins. But the gods live outside any moral codes. Humans mean nothing to them.”

I had the same feeling now. That some formless power existed and I was helpless in the face of it. I tried to snap out of my discomfort, and I began to walk in the direction of the strange sound when my fingers tingled. I tried to flex them but my hand had grown too cold and stiff. A heaviness descended on me as though my body had suddenly filled with sand. I turned around and struggled back to the cottage, my legs dragging so slowly it was like pushing through deep layers of mud.

I managed to wrest the door open and tumbled inside. Hanzi turned in his sleep and murmured. The coals from the fire glowed in the stove. Hanzi's old enamel kitchen clock ticked comfortingly. Our empty glasses sat where we'd left them on the table. Everything was peaceful. The tingling faded but I stayed awake the rest of the night, falling asleep only when the sun rose reassuringly at dawn.

When Dina woke me, Hanzi was already bustling about. The welcome aroma of coffee drifted through the cottage. While we drank it, Hanzi added a couple of hard-boiled eggs to our food cache and ushered us on our way. “You have a long way to go today,” he said. “You must start now.”

Twenty-Three

November 23, 2003

Les Alpilles, France

D

ina sat splendidly astride her horse, her long hair loose, tousled by the breeze. She looked over her shoulder every so often and gave me an encouraging smile. A good night's sleep had left her refreshed. Her sorrow of the night before had vanished and she seemed genuinely happy.

As for myself, despite Dina's good spirits and the scenic landscape, the feeling of trepidation from last night still clung to me. It had nothing to do with the prospect of curses. A malignance hung in the air, a disturbance in the natural order of things. We'd taken every precaution by spending only cash and not using our real names, except with Hanzi. But I was sure that I'd felt Alessio nearby last night.

We crossed local roads and passed through many fields. Vineyards cropped up as the land began to ascend in a gentle rise. We arrived at the little abandoned shack Hanzi told us to watch out for and turned onto the trail he recommended, which descended into a wooded area. The forest was made up of the kind of thick scrubby bush and weedy trees that grow on poor soil. Before long, our route narrowed to a rough path winding beside a stream. I dug into my shirt pocket and found my ballpoint pen inscribed with the insignia of the New York Knicks. I dropped it on the path. When we returned this way, we'd see if anyone was behind us and whether they took notice of it.

Clouds blocked out the sun. It grew cooler. The bush became much denser. I remembered Hanzi's description of getting lost in the marsh and thought, even here, how easy it would be to lose our way. Up ahead, Dina halted her horse and twisted around to talk to me. “The path dwindles to nothing ahead. I'm not sure what we should do.”

“Is there any way forward?”

“Yes, but it's marshy. I don't know if the water is just on the surface or deeper.”

Without waiting for my reply, she jumped off her horse and led him forward, testing the area gingerly with each step. She appeared satisfied the ground underneath the water was stable and remounted. I remembered Hanzi's advice to trust the horses. When the stallion plunged ahead, I figured we were safe.

We picked our way along, taking a labyrinthine route that headed vaguely northwest, in a strange country under difficult circumstances. Finally, I was elated to see a small rise. I shouted to Dina. She waved and quickened her horse's pace. Indeed, the path magically reappeared as the land rose and we entered a thicket of gorse and willow.

Yellowing leaves rustled behind us as we made our way through the grove. Odd, I thought, since there was almost no wind. We had to hold up one hand to protect our faces from the slapping branches as we passed through. Once we'd cleared the trees and the land was high enough to get a good look at the surrounding area, we'd regain some sense of direction. We might see, as well, whether anyone was tracking us.

We soon broke through the scrub and pulled to a stop. In front of us lay a large lagoon of black brackish water. In the middle of the turgid span sat an island covered with vegetation and debris. The dwelling centered on it brought a gasp of surprise to our lips. An old caravan painted in garish colorsâlime green, canary yellow, scarlet, and indigo.

“This must be Lagrène's house,” Dina said finally. “But how on earth do we reach it?”

Twenty-Four

T

he lagoon was smooth as black glass; not even a ripple stirred its surface. Nothing ruffled the plants either, as if the trees and reeds surrounding the little lake had been composed in a permanent tableau. It reminded me of the dead calm preceding a hurricane.

“Is she in there?” Dina asked. “She might not even be home.”

The caravan with its absurdly fanciful colors looked abandoned. I couldn't see any movement through the windows.

“She must have some way to get over there.” I searched for any sign of a boat or raft on the island or the shore but could see nothing.

“Maybe she flies over.” Dina laughed. “I wonder how deep it is.”

“The horses will tell us that.” I grabbed the mare's bridle and walked her down to the edge of the lagoon. The water looked oily, as if it were thickened with deposits. Yanking off my shoes and socks and rolling up my pants, I parted the reeds and took a few tentative steps into the sludge at the water's edge. It was cold and murky. I coaxed the mare to follow me in. She stretched her neck down to sniff at the water and refused to budge. “Hell,” I said. “There's our answer.”

The lagoon stank like an open sewer. No wonder the horses didn't want to go near it. The remains of weathered gray tree trunks with tips like broken spears stuck out of the water. They seemed to form a vague double line leading from the shore to the island, and I guessed an avenue of trees had once lined a drive leading up to the rise. If that was the case, the path between the rows of stumps might be more solidly packed than elsewhere underneath the lagoon.

I led the mare to where Dina waited. “Why don't you stay with the horses? If I tie the leads together I can loop one end around the tree trunks. That way, if there are any danger spots I can use the cable to pull myself out.”

Dina looked at the still expanse of water and glanced nervously back to the dense clumps of bushes and trees. “I'm not staying here alone.”

We secured the horses to the willows. I tied their blue leads together and fashioned a rough noose at one end. We both stripped down to our underwear, leaving only our shirts on; the rest of our gear went into our knapsacks. My apprehension aside, the sight of Dina's lovely bare legs and what was above, inadequately covered by the thin fabric of her underwear, got my testosterone shooting into overdrive. Good thing I'd started out first and she'd be behind me.

When we ventured into the water I tested the first few yards. My feet plunged unpleasantly into muck. It rose over my ankles until I found relatively solid footing. After a few throws I hooked the loop onto the first tree trunk about twenty feet from the shore. Dina pulled the line taut behind me. The water rose to the middle of my calves and then the pond bed seemed to level out. Lifting my feet produced a sucking sound; bubbles and greenish rotted matter floated up to the surface with every step I took. I thought I could feel live things slithering around my feet and my lips twisted in distaste.

As I approached the first tree stump the muck gave way to spongy water plants. My feet sank a little lower into the morass but it provided a kind of soft mat to walk on that was preferable to the mud. I looked behind and was glad to see Dina steadily sloshing through the water. The length of cable lying on the water surface trailed behind her like a long blue snake.

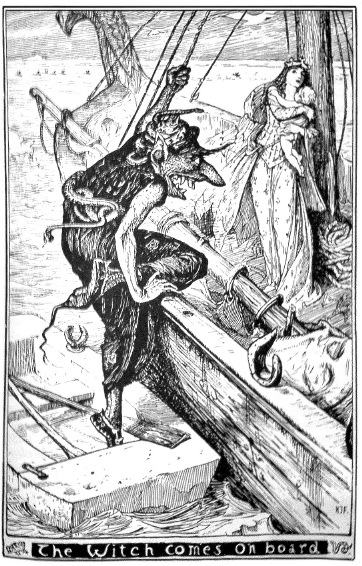

Slogging through the water toward the seer's house, I remembered a story I'd come across when I was a kid called “The Witch in the Stone Boat.” It left an indelible impression on me, probably because of the terrifying picture accompanying it. I'd found the story in a book stowed away in the bottom drawer of an old dresser and had no idea how it came to be there. Now that I'd learned more about fairy tales, I knew it was by the English fairy-tale collector Andrew Lang.

I could still recall the description of the witch, stooped over her long pole, her sinister figure in a small boat moving through the mist at night toward the ship carrying the prince and his bride. The witch stole into the young woman's body and banished the radiant bride to the underworld. It terrified me at the time and I insisted for weeks after that Evelyn leave my light on at night. One day the book went missing. I knew she'd thrown it away.

I surveyed my progress. Two more tree trunks and we'd reach the other shore. I pulled the loop off and, casting it toward the next stump, stepped forward. The mat of waterweed underfoot vanished. I plunged deep into muck and this time it swallowed my legs past my knees; it felt like a vacuum sucking me under. Something bumped against my ankle. I heaved my leg out and up came what at first looked like a large ball of wriggling red yarn. I'd stepped into a nest of long red worms and they'd risen to the surface, writhing around my skin. I batted them away furiously with my hand, which only dispersed them. They floated on the surface, trying to crawl up my thighs.

By Henry Justice Ford from

The Yellow Fairy Book