book JdM6x1406931-20978754

Read book JdM6x1406931-20978754 Online

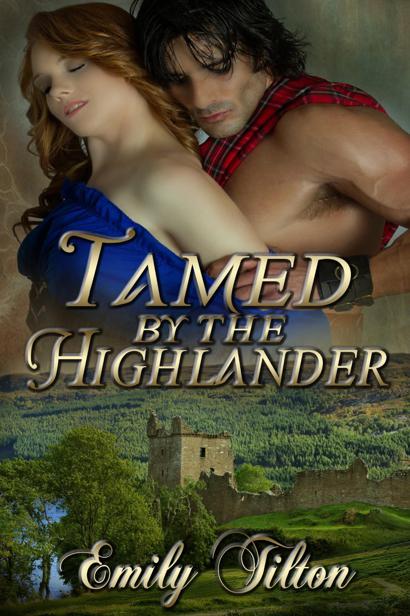

Authors: Emily Tilton

Tamed by the Highlander

By

Emily Tilton

Copyright © 2014 by Stormy Night Publications and Emily Tilton

Copyright © 2014 by Stormy Night Publications and Emily Tilton

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

Published by Stormy Night Publications and Design, LLC.

www.StormyNightPublications.com

Tilton, Emily

Tamed by the Highlander

Cover Design by Korey Mae Johnson

Images by Period Images and Korey Mae Johnson

This book is intended for

adults only

. Spanking and other sexual activities represented in this book are fantasies only, intended for adults.

Chapter One

Elisabeth Grant turned to look at the man in the pillory. She had only intended to glance at him for a moment, but when she rested her eyes upon his face, she realized that his own gaze was fixed upon her. She felt a hot blush spread itself across her cheeks.

Why had she even looked at him? Surely this Highlander did not deserve even to have the eyes of the Lady of Urquhart rest upon him.

She tried to look away but found to her confusion that she could not accomplish that simple thing but somehow must keep staring at the Highlander in the pillory.

Yes,

she thought,

he is certainly well made.

He had the rugged comeliness that seemed to be heaven's grace upon the MacGregors. His dark locks fell to his shoulders, now bowed in order that he might be fastened into the pillory. His eyes, which seemed somehow even darker than his hair, seemed to burn with a kind of angry amusement. His well-muscled frame, shirtless by order of her father's steward, with the plaid stripped down behind him, spoke of battles fought and probably won.

Who was he to be amused at Elisabeth Grant? Highlanders were proud, to be sure, and Elisabeth knew that in this man’s veins flowed the same fiery will to freedom and dignity that flowed in her own. But there were ranks and stations in this land, and it seemed to Elisabeth too much to bear that the sense of disrespectful fun that had brought this Highlander into the pillory had failed so noticeably to be extinguished by his humiliation.

Yes,

she thought as her blush spread further, having gained strength from the memory the Highlander’s gaze roused in her,

it was my fault I fell into the mire.

Indeed, before men and before heaven, I got no more than I deserved. But there are ranks and there are stations, and the Highlander should not have laughed at me.

Who was she, she asked herself, as she had so many times before. She was a Highlander herself, was she not? A daughter of Clan Grant, born here in the Great Glen? But when her mother had died, she had been sent to Edinburgh, and to be a Highlander in Edinburgh was to be a savage. For eight long years she had been told that she was a Lowlander, like her Stewart mother. Now, back in the Highlands, everything seemed to confuse her, especially when it came to men like Angus MacGregor.

Perhaps she should have let him be whipped after all. Surely that would have darkened those eyes even further. Surely there would be more anger than amusement in them now if he should know that she had watched his back being opened by the lash.

She managed to look away at last, but to her distress her glance fell immediately upon the servant whom she had been berating when she fell into the muddy ditch by the side of the market street. And old Mary had done nothing at all to deserve Elizabeth’s wrath—she could see that now. Elisabeth had been lording it over the servant, she knew now as she thought about it, only to make herself feel important as she strode through the little town that sat under the protection of Castle Urquhart.

Elisabeth suddenly felt close to tears. How was it that she could see the right, dignified, kind thing to do and yet always seemed to do the prideful, arrogant thing instead?

She stepped forward into the market square, hardly knowing why. She turned her face again to meet the Highlander’s gaze, which had not moved at all from her face. She was ten paces away, then five. The look in the Highlander’s eyes did not change at all, except that perhaps it grew more intense, both the anger and the amusement growing in relation to her drawing nigh.

“Man,” Elisabeth said, “your name is Angus MacGregor, is that right?”

“Yes, milady,” the Highlander said, somehow making it clear that he intended not respect but rather its opposite with the feigned politeness of his address.

Hearing the disrespectful way he said “milady”, Elisabeth’s blush, which had receded a bit, returned darker, she realized, than ever.

Truly, she had been intending to apologize, hadn’t she? But now her pride again got the better of her. “I am sorry, now, that I did not have you whipped,” she said. “Your face betokens an insufferable pride.”

“I am sure it does, milady, to such as you.”

“I do not take your meaning, or rather, I think it best for you if I do not take your meaning.”

“As you will, milady.”

Could she not even drive the amusement out by heightening his anger? She felt utterly defeated by this lowly clansman. She gave him a final stare, hoping that it might humble him, but instead she realized that she had simply made herself look more foolish. She turned and gesturing imperiously to the servants, began to walk back to the castle gate, tears of anger coming to her eyes as she realized how filthy her gown was. She realized that there even remained a whiff of dung upon her coif from when she had fallen into the mud and made MacGregor laugh at her, and she angrily ripped off the Lowland headdress, wishing for a Highland girl’s snood.

She persuaded herself that she felt better as soon as she was within the lower bailey’s great stone walls. Her castle—the castle of which she had been lady since her poor mother had died when she was ten years of age. Castle Urquhart, the most beautiful sight on all of Loch Ness. How she had missed it when she had been sent to the Lowlands for her education. How her heart had leapt when finally she returned, sailing up the loch, just a year ago.

Still feeling that all was not quite right within her, she hurried up to her favorite place atop the family tower, overlooking the loch.

“Lady of Urquhart,” she repeated to herself, in an old ritual that she had begun as a way to console herself after her mother’s death all those years ago. But now, as much comfort as she had derived from repeating it to herself over the years, she saw in it a pride that made her feel suddenly ashamed of herself. Pride, her father often said, was Elisabeth’s birthright. For if anything should happen to the elder brother whom she had never even met, she would be the heiress of Urquhart. Why did it seem now, back in the Highlands, that perhaps pride was everyone’s birthright?

More grieved now because her old ritual had failed her, Elisabeth turned to descend and to go to her chamber to dress for dinner. That was when she heard the alarm bell start to ring.

Elisabeth ran to the other side of the tower to overlook the battlements on the moat side of the castle and the little town beyond. Her coif fell from fingers that suddenly felt numb and fluttered down into the bailey.

Why are there no bowmen coming to take their places?

she thought as she peered over the crenellations. The sight that greeted her eyes on the other side of the keep gave her a much worse fright than the lack of bowmen. The raiding party was enormous—an army, it would be more accurate to call them—and they were already in the town. Only treachery could have allowed such a disaster. With dismay, Elisabeth thought on the fact that treachery to such a man as her father would perhaps not seem a terrible crime to many of his household.

She watched with astonishment as some of the guards inside the upper bailey began running through the central courtyard for the postern gate that led to the docks. Then her father himself, portly and undignified despite the furs he wore over his red silk tunic, appeared from the great hall, accompanied by his steward, Sir James Gordon. They began to head in the same direction. He was fleeing, she realized in an instant and with horror. He was deep in converse with Sir James as he went.

Suddenly, Sir James stopped, and called, “Lady Elisabeth? Lady Elisabeth?” She shrank back against the far battlement; she could hardly tell why. Then there were others calling her name, looking for her for a few minutes. But none found her, and soon enough all the voices died away, and she heard the shouts of the oarsmen as the boats departed down the loch.

She felt the tears rise in her eyes. She could barely remember when she had truly looked up to her father. Even when her mother had died, she remembered him only as a distant figure about whom her governess had said, “You must not trouble him.” And then she had been sent away and had seen him at most once a year. When she had returned, she had struggled to find in herself the pride of family and respect necessary to accord him the honor he was due from her, but she had managed. Watching him flee for the boats, the will to do even that had seemed to vanish from her.

Unaccountably, the memory of the Highlander’s gaze came into her mind. Unbidden, the thought rose:

how can my father truly have Highland blood? How could a Highlander ever flee like that?

No answer came back from her heart.

Now she began to run towards the stairs, hardly knowing where she was going, except that she was not going to the boats. As she ran out from the castle gates—which were still open, to her astonishment—and crossed the moat, she realized that the raiding party was within one hundred yards of her, hidden only by the buildings of the market square on the far side. If she tried to cross back over the moat and make her way along the curtain wall to the uncertain safety of the loch shore, they would surely see her even before she got around the angle towards the water. Perhaps if she went quickly across the market square she would be able to get through their disorganized advance and lose herself among the buildings. Barely even considering what she did, she began to walk quickly along the side of the square, trying to stay as close to the rough stone warehouse buildings as she could, hoping beyond hope to escape notice. As she did, though, her attention was arrested by what was happening in the middle of the square, for the Highlander was still in the pillory, although another man in an identical plaid was about to put an end to his captivity, wielding a woodsman’s axe that he brought down upon the locked fastening of the pillory.

“Go,” said Angus MacGregor. “I can find my own way.”

“Aye, that you can, I wager,” said his kinsman and sped away down a street that ran north towards the Clan Gregor lands.

Elisabeth pressed her back against the wall of one of the small warehouses that lined the square, trying to remain motionless. Why had she stopped? It was the Highlander, she was sure, who had somehow exerted his strange power over her. Whatever it was, though, there was only one thing to do. She willed her feet to begin moving again, and they did, carrying her further.

And she would have escaped the notice of Angus MacGregor entirely, so preoccupied was he with the various actions of stretching and rearrangement of a plaid attendant upon being freed from the stocks, if it had not come to pass that at that moment three MacDonald clansmen entered the square at the corner just where Elizabeth had hoped to exit it and be lost in the town. Their claymores were at their backs, and their dirks were in their hands. The one in front was looking straight at her.

“What is this?” said he. “Surely ‘tis the laird’s daughter.”

“Well, that’s a bit of good luck,” said a second.

“Are we going to miss our sheep for her?” asked the third.

“No,” said the first, “not at all.”

“She is a small bit of a thing,” said the second. “I can take her up and bring her with us. We can have our fun with her later.”

“Or along the way,” said the first, with a malicious chuckle.

During this conversation, Elizabeth had been unable to move a muscle, frozen in place with terror. Now that they began to advance on her, she found some will to turn about and to begin what she knew was a doomed attempt at escape.

To her astonishment, and also at first to her even greater fear, Angus MacGregor was standing behind her, holding the woodsman’s axe with which his kinsman had freed him.