Bones On Black Spruce Mountain (2 page)

Read Bones On Black Spruce Mountain Online

Authors: David Budbill

“Okay, then.”

“I think we ought to give ourselves a week, five days at least,” Daniel Continued. “It’s a long way up there and there’s no point in getting all the way up and having to turn right around and come back. We could start getting our stuff together in the morning, take off the next day.”

“Good,” Seth said. “I’m going home. I’ll ask Dad. No, Mom. No Dad would probably be best. Tonight, before chores. You do the same. Come up to my house after breakfast and We’ll start packing. That is if . . .”

“Don’t worry. They’ll say yes.”

By the time Seth reached home, supper was on the table. Halfway through the meal he could contain himself no longer. He couldn’t wait to find his father alone. Besides, it might be better if he asked them both at once. “Ah, Daniel and I want to go camping in the mountains, okay?”

“Not so fast,” his father said. “where do you want to go?”

“We thought we’d go up to Tamarack Brook to Raven Hill and make a camp up near Morey’s old sugarhouse, where I was last fall. Then we could explore lost boy brook ravine from there and climb around on Eagle Ledge and Black Spruce. We’d be gone about five days.”

“I don’t know,” his father said. “That’s a long time to be away. It sounds like risky business to me.”

“It does to me too,” his mother said, “but he spent the night alone in the swamp last fall and that went all right. He works around the farm like an adult now; he’s getting older. I’m worried too, but I think we should let them do it.”

“Well I suppose. But I don’t like it much.”

Seth wanted to shout, but he didn’t. All he could think about was what was happening a mile down the road.

The next morning as Seth and his parents sat eating breakfast, Daniel came running up the lane. He Burst into the house panting like a dog. The smile on his reddened face said it all. Seth’s mother laughed. “Well, I guess that settles it.”

His father wasn’t laughing, only smiling a kind of halfhearted smile. “I suppose it does.”

“Come on, Daniel, let’s go into the living room.”

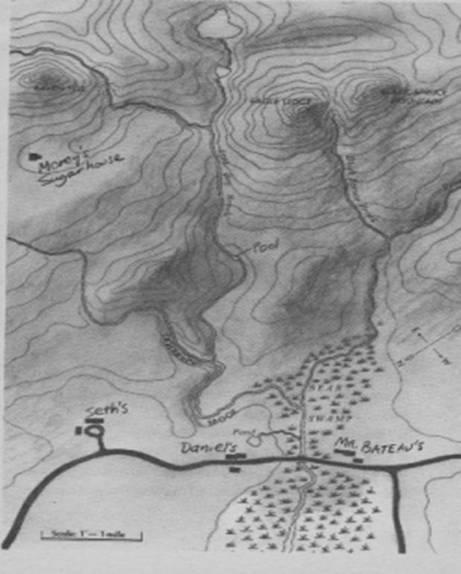

Seth spread the topographical map out on the living room floor.

“We could take off from your house,” Seth said. “We can work our way up the Tamarack, up through here, and fish as we go. Then we can make camp near Morey’s sugarhouse the first night.”

“Maybe we shouldn’t spend time fishing until we get our camp built,” Daniel said. “we don’t know exactly how long it’ll take us to get to the sugarhouse. It looks like it’s about four miles from my place.

That’s a pretty good walk for one morning through that kind of country with our packs. If we could get there in time for lunch, we’d have the afternoon to fish and get camp built”

“You’re right,” Seth said. “We probably shouldn’t fish on the way up. It took me a long time to get up there last fall. Hey maybe we won’t have to build a camp the first day. Maybe we can spend the first night in the sugarhouse. There’s a shed off the back; I saw it last fall. There’s even a bunk and a stove in it. I bet if we cleaned it up a little, it would make a good camp. We could dump our stuff and go down to Lost Boy Brook and catch our dinner.”

“Good idea. Then the next day we could fish, lie around and stuff, and get ready for our climb to Eagle Ledge and Black Spruce.”

“Yeah.” Seth lowered his voice so his parents couldn’t hear. “maybe we could climb down the cliff on Black Spruce. Let’s take some rope.” Then his voice grew louder again. “When we got back, we could spend another night or two in camp and come home. Four or Five days. That’s what I told Dad.”

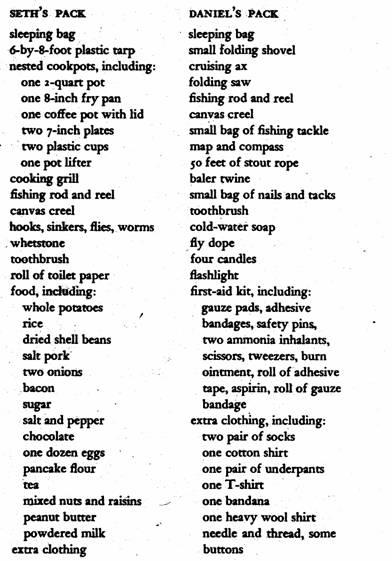

With that settles, the boys began to get their equipment together. They tried to divide the weight evenly between the two packs.

Each pack weighed about twenty-five pounds, easy to carry across a room, but another matter entirely to carry miles and miles up a mountain.

Early the next morning Seth and his parents arrived at Daniel’s house. As the boys prepared to leave, their parents stood chatting nervously, trying not to show the concern they felt. Old man Bateau was in the kitchen too.

Mr. Bateau was the next neighbor down the road. He lived alone. Almost every morning he came by to pay a call and gossip. The boys liked Mr. Bateau. He was the oldest man on the hill and full of stories about the wilderness. Until his wife died, Mr. Bateau had milked cows like the rest of the farmers on the hill, but he was never what you call a farmer, not the way Seth’s and Daniel’s fathers were. Old man Bateau never really cared for cows. He was first and foremost a woodsman, a logger. He was always the first man into the woods in the spring to cut next year’s fire wood. He was never really happy unless he smelled of sweat and pitch. Mr. Bateau was seventy-five now, but he could still work a day in the woods as well as any man. It seemed to the boys he knew more about the woods and the animals than any person alive.

He had taught them everything they knew about camping. He was the one that showed them how to make a lean-to out of poles and boughs, how to start a fire with yellow birch bark, how to build a fire pit so that food would cook slowly and not burn. He had been a good teacher.

When he heard the boys were making a trip, the old man’s eyes sparkled. He seemed almost more excited than they were. The boys knew somehow that only old man Bateau understood how much they wanted to go to the mountain.

“So you babies go to da woods, eh?” Mr. Bateau often called the boys babies. Had anyone else in the whole world referred to them that way they would have been fighting mad, but coming from Mr. Bateau it was okay. They understood; in fact, they liked it. “I wish I could go too. You little fawns be careful. Da woods is good. Dey make you grow, ‘cause you see strange t’ing der. You see fear. Dat good for you. But be careful! Da woods don’t care for you da way your mudder and fadder do. Day soon as see you die up der as come back. Da woods don’t hurt you, but dey don’t he’p you neider. You mus’ be smart in da woods, not dumb like a cow. Da woods dey stronger dan little babies. Watch like a deer, den you be okay.

“You boys go to da mountain too, no? Yes. I know. I go der once too, long time ago. You boys go look for da bones, too. I know, I know. Da bones no good! Stay away from da bones! Dat little baby lost and starved to death in dat cave, poor little t’ing, he go crazy; dey heard him cryin’ in da night. Stay away from da bones! My fadder seen ‘em once when he was young and dey turn his hair white as January. He see da fear too, only he be lucky; he come back. Babies you do what I ask you; don’t go near da bones!’

There it was again. Seth and Daniel had heard the story of the bones on Black Spruce Mountain a thousand times it seemed. Every kid in Judevine knew the story.

Seventy-five years before, in hardwick, the town on the otherside of the mountains, there was an orphan boy whose foster father beat him mercilessly. The boy ran away one day, off into the mountains, and was never seen again. Although search parties were formed and the mountains combed throughly, not a trace of the boy was ever found. Years later someone, nobody knows exactly who, found the skeleton of a boy in a cave on the western face of Black Spruce Mountain. The bones lie there to this day, or so the story went. Some people said that since the boy was never properly buried, his ghost haunted the mountain.

For a few years after the boys disappearance, during haying, always during haying, people could hear howling, or maybe it was crying, from the mountain. Everyone agreed there was a strange sound up there, but they couldn’t agree what made the sound. Some said it was just bears howling like they sometimes do in the summer. Others claimed it was young coyotes. Others said it was proof there was still a panther up there. Still others said it proved the spirit of the boy really did haunt the mountain.

Mr. Bateau’s version of the story said that the boy didn’t die right away, but rather that he learned how to survive and lived up there in the cave for years. Mr. Bateau claimed that the cries the villagers heard weren’t made by a ghost but by the boy himself and that the cries were cries of loneliness.

For a few years after the boy disappeared, strange things happened on Mr. Bateau's farm. At that time Mr. Bateau's family lived on Daniel's place. The first year, in the fall, some canning jars of vegetables and meat disappeared from the cellar, and a couple of horse blankets and an old pair of woolen pants disappeared from the barn. The Bateaus were never sure that the things were actually stolen; maybe they were just misplaced, but it was strange nonetheless. Then the second year no food or clothing disappeared, but a shovel and a hoe came up missing. After that, for a few years nothing very unusual happened, but occasionally a part of an old machine or a piece of scrap metal or a small can of nails would be gone. Then nothing, no strange cries from the mountain, no little thefts, nothing.

Slowly, over the years, people forgot the details of the story. Slowly the tale took on the sound of something from a book. Everybody more or less forgot—everybody, that is, except Mr. Bateau.

When Seth and Daniel were younger, they were frightened by the story and believed it. Now that they were older, they realized that grown-ups told the story because it was a good yarn, but they knew nobody really believed it. Seth and Daniel didn't really believe it either.

Nobody believed the story except the little kids and Mr. Bateau, and Mr. Bateau was old and a little peculiar. At least that's what people said. Nobody alive had ever seen the bones. Old man Bateau's father was the last man said to have seen them and he'd been dead for years. And since nobody went up to the mountain, nobody even knew whether there really was a cave on the western face. Anyway, it would be impossible for anyone to survive up there. It was just a story, a story for little kids and old men who were kind of crazy. But though the boys doubted the story, it still fascinated them. The possibility that it might be true added excitement and mystery to their plan.

By the time Mr. Bateau had finished talking, the boys were ready. They mounted their packs, kissed their parents good-bye, and headed down the lane toward the meadow behind the barn.

"You boys be careful!" Daniel's mother shouted.

"We will!"

The five adults stood in the dooryard and watched the boys grow smaller as they moved across the meadow toward the woods. Then the long early-morning shadow of Black Spruce Mountain fell on them and took them in.

In the batting of an eye they were gone, swallowed by the woods, and there was nothing left to look at but the mountain reaching darkly into the sky.

Chapter 2

Seth and Daniel struck the old logging road that ran alongside Tamarack Brook and headed upstream. It was a warm, clear day and the cool shade of the woods felt good. Already their pace had slowed from the fast, striding eagerness with which hikes always begin to a slower, steadier gait, the sure sign of those who know that there are many hard miles ahead.

"Daniel, do you think Mr. Bateau really believes that story?"

"Nah, how could he?"

"I don't know, but when he tells it, it sounds so real. And he sounds so sincere."

"I know."

"Maybe he's right," Seth went on. "He was right about the beaver pond and the big trout in the middle of the swamp. Nobody believed that story either until we showed them proof. I hope he is right. If we could find the bones, we could prove to everybody he was right about that too."

"Well, I don't believe the story. Look, Seth, have you ever seen or heard a ghost? All that stuff can be explained. Can you imagine a kid surviving up there for years? It's impossible. He'd freeze to death the first winter. What would he eat? How would he stay warm? It's impossible. All of it's impossible and you know it. Why would a kid do such a thing any-way? There's nothing to that story and there never was."