Bone Jack (22 page)

Authors: Sara Crowe

Ash expected Callie to argue, for all that stubborn fire inside her to blaze out. But instead she just nodded, stood up. In her torn and muddy dress, her dark hair still wind-knotted, she looked like a lost child.

‘Home it is then,’ said Mum.

THIRTY-SEVEN

The spare room where Dad had been sleeping. Curtains and window open and sunlight pouring in. All the junk gone, removed to the garage. A red rug on the floor, the bed made up with clean sheets, a duvet.

Callie stood in the doorway, watching Dad angle a little bedside table into place.

Dad looked rough but he smiled at her. ‘Will this do for you?’ he said.

Callie nodded, solemn and silent.

‘Tomorrow we’re going to visit your grandpa in hospital and arrange to pick up your things from his house,’ said Dad. ‘You’ll feel more at home when you’ve got your own things around you.’

Outside the window, a rook alighted on a branch of the old apple tree and preened its feathers in the soft light.

Dad and Callie watched the bird and Ash watched them and thought how they were both broken but both still standing, sometimes faltering, falling, yet getting up again, keeping going.

He left them there, went outside and sat on the bench at the front of the house. Dark clouds rolling over Tolley Carn. Beyond it, blackened slopes where the wildfire had burned itself out. Here and there, faint scarves of smoke trailed where the land still smouldered.

A rook winging past.

Where were they now, the ghostly stag boy, the hounds, the wolf?

Bone Jack’s voice in his head.

Back where they belong

, it said.

Back where it’s quiet, where they can rest.

Mark, smashed and hollowed out, his summer burn faded under the stark hospital lights.

Ash stood in the corridor, watching him through the glass pane in the door.

‘Are you going in?’ said Dad. ‘Don’t be too long. He’s still in a bad way.’

‘Dad, I don’t know what to say to him. What should I say to him?’

‘Just say the first thing that comes into your mind,’ said Dad.

Ash nodded, drew a deep breath and went into Mark’s room.

‘Why didn’t you kill me?’ he said.

The wind keened at the window. Grey sky, a slash of rain glittering on the glass.

The summer over.

Mark still strapped into casts, his eyes closed, tears silvering his cheeks.

‘Why didn’t you kill me? Why did you change your mind?’

Nothing.

‘I need to know.’

‘I almost did kill you,’ said Mark.

‘I know. Then you stopped and tried to save me. Why?’

‘Because of what you said about my dad saving your dad’s life up there. Because you were alive, and you wanted to live.’

Ash shook his head. Not good enough. ‘What does that mean? I don’t know what that means.’

A long silence, then Mark started to talk. ‘You know when my mum died? We were friends so you know all about it. It was a long time ago. Half my life. But I remember it like it only just happened. I remember all of it. It was like part of my dad died too, when Mum did. Like we lost them both. He hardly ever smiled after that. He just worked. All the time, working. And then last year there was foot-and-mouth and I was out there for hours with him, day after day, bringing our sheep down from the mountains, watching the government men kill them, watching them burn. He couldn’t take it. Then he hung himself.’

‘And you found him. Callie told me.’

‘She doesn’t know everything. I didn’t tell her everything.’

‘Didn’t tell her what?’

‘That he was still alive when I went into the barn. He was up there in the hayloft, where you and I used to mess around. He’d already tied the rope to a rafter. He already had the noose round his neck. And I went in and I guess I yelled or something because he looked straight at me. Straight at me, Ash. And then he jumped anyway.’

Ash couldn’t breathe, couldn’t speak. In his mind’s eye he saw it all. The barn at night, Mark going in, looking up. And Tom Cullen, his expression cold and faraway, already out of reach. Then falling through the darkness.

The crack of his neck breaking.

‘It’s OK,’ said Ash softly. ‘You don’t need to tell me any more.’

And there was no need. He knew it all now. How Mark couldn’t get his dad’s death out of his head. How he’d tried to erase it, make his dad’s death unhappen. How everything had got jumbled up in the madness of his grief: the folk tales his dad and grandpa used to tell, the Stag Chase, the ghostly hound boys drawn to his pain, no more than breaths of mist at first but growing stronger all the time. Mark had come to believe that if he killed the stag boy, he could bring his dad back from the dead. Life for life.

But in the end, Mark had chosen life and the living over the dead.

‘What happens now?’ said Mark.

‘You’ll go stay with your grandpa when you get out of hospital. Then we just get on with it, I suppose,’ said Ash. ‘One foot forward, then the other.’

Mark gave a weak smile. ‘So cheesy.’

‘I know,’ said Ash. ‘It works though. You should try it. You just keep going until you get to where you need to be. That’s how we got you down off the mountain.’

‘I don’t remember any of that,’ said Mark. ‘I remember trying to push you off the Leap. There was this look in your eyes, like you still couldn’t believe I’d really go through with it, even though you were inches from the edge. You still trusted me somehow. Then you told me about how my dad saved your dad and suddenly it was like I was standing outside myself, watching this crazy person trying to kill you, only the crazy person was me. And I knew my dad wouldn’t want that, no way, and I kind of froze. I couldn’t do it. But the ghost hounds rushed us and you lost your balance and I lunged and grabbed you but we both fell. I remember going over the edge, and after that I don’t remember anything until I woke up here. I don’t even know how you climbed up from that ledge we fell on to.’

‘It was the stag boy,’ said Ash. ‘The ghost stag boy. They must have hunted him up there, centuries ago, and he fell off the Leap and landed on that ledge, and he climbed up. He showed me how to do it. He survived and so did we.’

Tears glittering on Mark’s cheeks again. ‘I’m sorry,’ he said. ‘I’m so sorry.’

‘It’s OK,’ said Ash. ‘We made it. We both made it home.’

A knock at the door. Dad came in. ‘You ready?’

‘Yeah,’ said Ash. He stood up, looked at Mark. ‘I’ll come back tomorrow, if you like.’

Mark smiled. ‘Yeah. That would be good.’

THIRTY-EIGHT

Early November. The leaves on the beech trees like copper shields. The nights drawing in and the mountains ghostly with low cloud. Soon there would be snow on the high peaks, ice cracking underfoot.

One day he found Callie in the garden, crouched. In her cupped hands, a tiny brown bird, loose with death. Its eye was still gleaming, a bead of bright blood on its beak.

‘It flew into the window,’ she said, and sobs shook through her.

He touched her shoulder, turned away, went back inside the house.

There were no races he could run for her, no trophies he could lay at her feet.

There was only damage that would take a long time to heal.

From his bed, he watched the trees move in the wind.

He thought about Callie, and the bird. He thought about Mark, the stag boy, Bone Jack.

It still wasn’t over. Not yet.

Next day he walked up the lane, past winter-black trees and silent fields, along the old drovers’ paths through the mountains to Corbie Tor.

In the valley below, the sluggish stream of summer was now a little rushing river, sparking in the late-morning sunlight. The autumn winds had stripped most of the leaves from the thorn trees. Heavy clusters of haws the colour of dried blood hung among their dark boughs.

He went down, jumped rock to rock across the river, pushed his way through the thorn trees to the bothy with its grimy windows and the bone strings rattling in the doorway.

A rook flapped down and settled on a branch. Then another, and another. They shook out their feathers and filled the air with their rough cries. He waited, half expecting Bone Jack to appear through the trees, but Bone Jack didn’t come.

Ash stood outside the doorway in a drift of dead leaves. He hesitated. Then he stepped inside.

No one there. Everything was as he remembered it: the fox skull on the shelf, the old army knife, the flint arrowheads. The book.

The book he’d taken last time he came, the old copy of

The Battle of the Trees

that the wind had ripped apart in his hands. Only now it was intact once more, and back where he’d found it.

I have been in a multitude of shapes,

Before I assumed a consistent form …

He closed the book and went outside.

The autumn sun low over the mountains.

The mew of a buzzard.

A cold wind blowing.

Ash ran. Ran past Corbie Tor and along the high paths and soon a shadow ran with him, a shadow that became a clay-daubed boy with a great wolf racing at his side. And Ash and the stag boy ran and laughed for the joy of it, for the wildness of it, for the fierce beauty of the wolf and for the story of the land that had not yet ended, that would never end.

Acknowledgements and Author’s Note

Special thanks go to my agent Joanna Swainson, my editors Eloise Wilson, Charlie Sheppard, and Ruth Knowles.

The lines from

Cad Goddeu (The Battle of the Trees)

used in

Bone Jack

are taken from William F. Skene’s translation in

The Four Ancient Books of Wales

(1868).

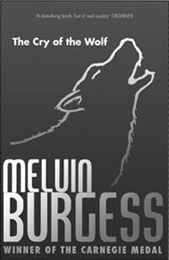

The Cry of the Wolf

MELUIN BURGESS

‘A writer of the highest quality with exceptional powers of insight.’

Sunday Times

It was a mistake for Ben to tell the Hunter that there are still wolves in Surrey. For the Hunter is a fanatic, always on the lookout for unusual prey. Driven by an ambition to wipe out the last English wolves, the Hunter sets out on a savage quest. But what happens when the Hunter becomes the hunted?

‘A disturbing book, but of real quality; you will applaud the end.’

Observer

‘A Dickens of the future.’

Michael Rosen

9781849393751

£

5.99