Bombsites and Lollipops: My 1950s East End Childhood (6 page)

Read Bombsites and Lollipops: My 1950s East End Childhood Online

Authors: Jacky Hyams

Tags: #Europe, #World War II, #Social Science, #London (England), #Travel, #General, #Customs & Traditions, #Great Britain, #Historical, #Biography & Autobiography, #Military, #History

‘I’ve ’eard nuffink from those bleeding bastards down the ’ousing department Mrs ’yams,’ was Mrs Cooper’s perennial greeting.

‘ ’Ow do they fink we can bring up two kids in a piss ’ole like this?’

She had a point. The Coopers had an outside loo but no bathroom; they’d have to go to Hackney Baths once a week, if that, if they wanted a bath, rather than a strip wash. The third bombsite, at the other end of our street, had also been a family house. When we moved into the area it was nothing more than bricks, dust, debris and rubbish; indeed, it gradually became a bit of a playground for local roughnecks, until the authorities constructed a tin wall around it, too high for even the most determined street chancer to clamber over.

Over time, this site became a sort of tumbledown car yard, run by an older man called Charlie and his son, Len. It was never really clear what they actually did inside the yard – or how they’d come to acquire the site from the authorities – but from time to time, as I grew up, you’d see them tinkering with various kinds of vehicles in the yard, sometimes at night.

Len and Charlie were unfailingly polite to my mum when she passed, always greeting her cheerfully, sometimes even offering to help her if she had heavy shopping. But there were no proper conversations. In a way, their attitude to us was more like a bit of forelock tugging, respect for your betters, than normal everyday neighbourliness. We stood out like sore thumbs in our milieu: smartly dressed, well fed, living a well-shod life in these squalid surroundings.

As for the other flat dwellers, we mostly just glimpsed them in passing. Families came and went in some of the other dwellings without us ever exchanging more than the odd hello. Apart from Maisie and Alf in the centre ground-floor flat, that is, who were pointedly ignored by us after the Chocolates Incident. They’d drawn a bit of a short straw when they moved in: their front entrance was directly behind the entry door for all the rubbish that poured down from all floors via The Chute.

Everyone in the block had one thing in common: we detested everything about The Chute, an unsanitary and unsavoury repository for the block’s rubbish. Each floor had access to a wall-mounted square metal opening to The Chute; you climbed up or down one flight of stairs to get to it. Yet the opening itself was badly designed and far too narrow for the amount of rubbish that got chucked down it. As a result, The Chute was frequently blocked. To compound matters, rubbish collection from the tip that piled up behind the ground floor door was pretty unreliable. So in summer you frequently held your nose as you clambered up the stone stairs as a couple of weeks’ worth of rubbish lay festering behind the door. The block stank to high heaven – and buzzed with flies.

In the flat directly above us lived Mary, a blind woman in her late fifties, alone and cut off from the world. Relatives would shop for her and bring the necessities to her door or give her a hand once a week. And about once a year, someone would collect Mary, help her down the six steep flights of stone stairs, and take her out for the day. The rest of the time she lived there, frustrated with her lot – who can blame her? – but venting her spleen by using the only resource available to her: making our lives miserable with noise, banging about her tiny kitchen, thumping around in her bedroom at odd hours of the day and night. Noisy housework at midnight was a perennial favourite.

‘I’m gonna fucking go up there and sort ’er out,’ Ginger would threaten when Mary’s banging and thumping reached crescendo levels. The poor construction and paper-thin walls of the flats made it very easy to create havoc this way – and Mary knew this, all too well. She’d managed to survive in her top-floor flat right through the Blitz – time enough to practise her banging and thumping act to perfection.

‘Don’t, Ging, she’s a lonely old blind woman,’ my mum would plead and, most of the time, my dad would relent and keep the peace. But there was the odd occasion when the noise from above would be too much, especially if it interrupted my dad’s slumber. Then he’d stomp up the stairs in rage and hammer on her door.

‘Whaddya bloody well think you’re doin’ you stupid cow! Stop that bloody bangin’ or I’ll ’ave the coppers on ya!’

This was, of course, an empty threat. Rousing the coppers of Dalston was not part of my dad’s repertoire. And Mary didn’t even come to the front door. Yet my dad’s aggressive tactic was effective. The banging would stop, sometimes ceasing for weeks on end. Until the next time frustration at her existence would overwhelm her and the noise would start up again. Eventually, she moved out. Rumour had it she went into an old people’s home, only to be replaced by an amorous young couple who spent most of their waking hours humping and grinding, puffing and panting, in their bedroom, creating an even more sensitive noise problem that was more or less impossible to resolve. (Even my dad would have baulked at climbing the stairs to yell, ‘Stop bloody knockin’ ’er off!’)

The only neighbours we had anything to do with were the married age-gap couple in the flat next door. Harry, a skinny, moustachioed, somewhat seedy man in his fifties, a fancy-goods dealer, and his rather svelte blonde wife Sophie, whom he’d met at a West End dance hall just after the war.

Sophie was in her twenties, a half-Jewish refugee from Austria. And my mum became quite friendly with her over time; mainly, I suspect, because they had a common dislike of their environment – and couldn’t quite understand how they’d wound up there.

Molly was convinced Sophie had married for reasons of security only.

‘He did well during the war with the black market, so she must’ve thought he’d be a safe bet, what with having no family here and not wanting to go back to Austria.’

She was probably right. Yet the marriage, like other similar hasty liaisons of the time, was doomed to be quietly unhappy. Sophie was alone for much of the time – Harry frequently travelled around the country for work – and the pair had little in common. She fruitlessly craved the childhood joys of her cultural background, things like classical music and ballet; he preferred Vera Lynn and, later, Dickie Valentine records: you’d always know when Harry was back from a trip because you’d hear Vera belting out, ‘There’ll be Bluebirds Over The White Cliffs of Dover’ from their front room. Harry had also made it plain he didn’t want kids, so Sophie envied my mum, having a little girl to love and look after.

‘I make a big mistake – and now I pay for it,’ she’d tell Molly.

When Harry was away, Sophie initially babysat me for my parents a few times. But while my dad liked Harry, a fellow traveller in the East End world of ducking and diving, he had an uninhibited aversion to ‘the German cow’. To my dad, there was no distinction between the Austrian and German population, even though Sophie said she’d come here to escape persecution. As far as he was concerned, they were all, men and women alike, tarred with the same brush. He even suspected Sophie’s half-Jewish status was a ruse, to make her more acceptable as a refugee.

‘Irma Grese was a woman,’ he’d remind my mum if she tried to protest on behalf of her neighbour (Grese, executed for war crimes at the age of twenty two, had sadistically killed hundreds of inmates during her time as a warden at Belsen concentration camp), and in due course, Ginger stopped the babysitting.

‘It’s bad enough she’s living next door,’ was his rationale. ‘I don’t want her in my home looking after my kid.’

In fact, my dad didn’t like anyone coming into our home. OK, it was small and damp and a tad depressing. But that wasn’t the reason why I grew up in a place where we never entertained or rarely had visitors. The truth was, Ginger was somewhat possessive: he wanted his wife and kid right there, away from everything and everyone else.

No one, neighbour or relative, was actually invited into our home. Even when he wasn’t there, my mum wasn’t encouraged to invite people in for a cuppa or a chat. As I grew up, the only other person who’d come to our flat regularly would be Annie, our Irish cleaner.

Sarah, of course, had been around, visiting us occasionally after Ginger returned from India. But in 1947 she went off to live overseas permanently. And my mum’s family had scattered, some abroad, the rest to other parts of the country. As for my dad’s parents, we always went to them. They never ever came to us.

The one thing my dad couldn’t control, however, was the unexpected occasional knock on the door out of the blue. Although we’d had a big black Bakelite phone in the living room from as far back as I could remember, many people then didn’t have a home phone. So an unexpected knock on the door was a pretty normal occurrence for everyone else.

When we did get a rare, unheralded knock at the door from one of my mum’s UK-based brothers, either bachelor Eddie (whom Ginger disliked because he was a habitual gambler and often on the scrounge) or Joe, my mum’s favourite brother, who ran a gift shop in Brighton and had two daughters, my mum would be delighted. She’d rush into the kitchen, raid the larder and prepare all sorts of delicacies, egg or smoked-salmon sandwiches, teacakes, biscuits, drinks. Generous and open-hearted, she loved pulling out the stops to entertain for these unexpected rare visits; if my dad was there, he’d grit his teeth and keep up the façade of hospitality.

As for me, I was only used to being the sole focus of two people’s lives and found such unexpected visits uncomfortable. I lived in the glow of my mum and dad’s attention, taking it for granted that I was the centre of the entire universe. Adjusting to other people’s company in the small confines of our flat, even briefly, seemed strange, an unhealthy beginning, which didn’t do me any favours when it came to relating to others’ needs later in life. So all I felt back then, once the visitors had departed and I’d been given the obligatory hug and kiss (which I hated: I was not a kissy-feely child) was an overwhelming sense of relief. ‘I hope they don’t come back,’ the little voice inside me said. ‘I don’t like them coming round here.’

So while we rarely had visitors or neighbours over, in turn, my mum only ever ventured into Sophie’s flat for tea and chats when my dad was at work. And in due course that stopped too – because of my dad’s over-the-top feelings about the war. He wasn’t alone in this, of course. If you’ve been bombed to smithereens, lost members of your family, spent years in army uniform or wound up a prisoner, you’re bound to have strong opinions on what had happened. But holding a young, fairly innocent refugee woman responsible for the slaughter and destruction of millions of lives was a bit rich. Though I can see now, that it wasn’t really just about the war.

As I said, my dad just didn’t want anyone coming into our home.

S

UNDAYS

S

undays in post-war London were another planet away from the Sundays we now take for granted. Silent streets; virtually everything closed. Pubs open briefly at lunchtime and for a couple of hours at night. Everything else ground to a halt, apart from buses and trains. No supermarkets or round-the-clock shopping opportunities. People visited each other. Or they stayed indoors. And my early world was dominated by a late Sunday-afternoon routine that was unwavering in its rigidity: rain or shine, Molly and I would be required to pay homage to my father’s parents, Miriam and Jack, a few miles away, just off Petticoat Lane in Stoney Lane. Ginger would eat his Sunday roast and then head for bed, sleeping off the week’s rigours, preparing himself for the next. Sunday was the only night he was virtually sober.

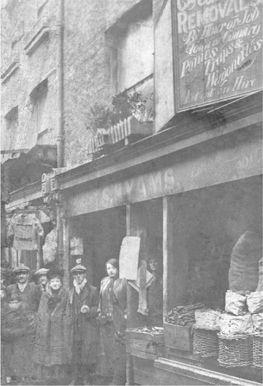

Snug in my little beige wool coat with its velvet collar, a bow tied atop my frizzy curls, I’d clutch my mum’s hand tightly as we headed down Shacklewell Lane, past the big synagogue and the hairdressers on the corner to wait for the 649 trolley bus ride that took us on the two-mile journey down Kingsland Road, past Shoreditch Church and Itchy Park (so named because of the tramps that used to doss there), down past Commercial Road and finally to Liverpool Street Station.

Increasingly nervous during the bus ride, my childish fear would start to become near panic, stomach churning, when we alighted outside Dirty Dick’s pub. This was the truly horrible bit, the thing that gave me nightmares: the ten-minute walk through the near deserted Middlesex Street to Stoney Lane down the dark, narrow, dirty and eerie thoroughfares. At three years old, I’d absorbed much grown-up talk about the grisly, blood-splattered Victorian history of the area, mainly the Whitechapel Murders, when a series of young prostitutes were found murdered and horribly mutilated, many of these crimes reputed to have been committed by the knife of Jack The Ripper.

This gruesome gossip about the Ripper’s ghastly slayings usually came from my grandmother, Miriam, probably because she and Jack lived just a few hundred yards away from The Bell, an ancient pub on Middlesex Street where, it was said, twenty-five-year-old prostitute Frances Coles, the last victim of the Whitechapel Murders, had drunk her final tipple with one of her clients in 1891. Hours later she’d been found, bleeding to death, her throat slashed, in a nearby street.