Bold They Rise: The Space Shuttle Early Years, 1972-1986 (Outward Odyssey: A People's History of S) (23 page)

Authors: David Hitt,Heather R. Smith

Tags: #History

Whenever we’d go to take a drink, . . . a large percentage of the volume was hydrogen bubbles in the water, and they didn’t float to the top like bubbles would in a glass here and get rid of themselves, because in zero gravity they don’t; they just stay in solution. We had no way to separate those out, so the water that we would drink had an awful lot of hydrogen in it, and once you got that into your system, it’s the same way as when you drink a Coke real fast and it’s still bubbly; you want to belch and get rid of that gas. That was the natural physiological reaction, but anytime you did that, of course, you would regurgitate water. It wasn’t a nice thing, so we didn’t drink any water. So we were dehydrated as well; tired and dehydrated when it was time to come back in.

18.

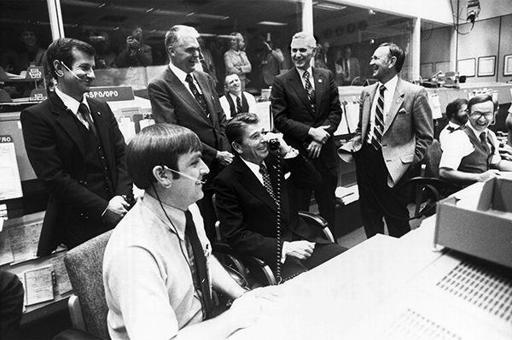

From the Mission Control room at Johnson Space Center, President Ronald Reagan talks to Joe Engle and Richard Truly, the crew of

STS

-2. Courtesy

NASA

.

In addition to the strained physical condition of the crew, other factors were complicating the return to Earth. The winds at Edwards Air Force Base were very high a couple of orbits before entry, when the crew was making the entry preparations, leading to discussion as to whether it would be necessary to divert to an alternate landing site.

Even under the best of circumstances,

STS

-2’s reentry would have had a bit more pressure built into it—another of the test objectives for the second shuttle mission was to gain data about how the shuttle could maneuver during reentry and what it was capable of doing. The standard entry profile was to be abandoned, and about thirty different maneuvers were to be flown to see how the shuttle handled them. In order to accomplish this, the autopilot was turned off, making Engle the only commander to have flown the complete reentry and landing manually.

“Getting that data to verify and confirm the capabilities of the vehicle was something that we wanted very much to do and, quite honestly, not everyone at

NASA

thought it was all that important,” Engle recalled.

There was an element in the engineering community that felt that we could always fly it with the variables and the unknowns just as they were from wind tunnel data. . . . Then there was the other school, which I will readily admit that I was one of, that felt you just don’t know when you may have a payload you weren’t able to deploy, so you have maybe the

CG

[center of gravity] not in the optimum place and you can’t do anything about it, and just how much maneuvering will you be able to do with that vehicle in that condition? How much control authority is really out there on the elevons? And how much cross range do you really have if you need to come down on an orbit that is not the one that you really intended to come down on? So it was something that, like in anything, there was good, healthy discussions on, and ultimately the data showed that, yes, it was really worthwhile to get.

(In fact, after

STS

-2, maneuvers that Engle tested by flying manually were programmed into the shuttle’s flight control software so that they could be performed by the autopilot if needed in the future.)

And so, with a variety of factors working against them, the crew members began the challenging reentry. “We had a vehicle with a fuel cell that had to be shut down, so we were down to less than optimum amount of electrical power available,” Engle recalled.

The winds were coming up at Edwards. We hadn’t had any sleep the night before, and we were dehydrated as could be. And just before we started to prepare for the entry, Dick decided he was not going to take any chances of getting motion sickness on the flight, because the entry was demanding. . . . He had replaced his scopolamine patch [for motion sickness] and put on a fresh one. The atmosphere was dry in the orbiter and we both were rubbing our eyes. We weren’t aware that the stuff that’s in a scopolamine patch dilates your eyes. So we got in our seats and got strapped in, got ready for entry, and I’d pitched around and was about ready for the first maneuver and said, “Okay, Dick, let me make sure we got the first one right,” and I read off the conditions. I didn’t hear anything back, and I looked over and Dick had the checklist and he was going back and forth and he said, “Joe Henry, I can’t see a damn thing.” So I thought, “This is

going to be a pretty good, interesting entry. We got a fuel cell down. We got a broke bird. We got winds coming up at Edwards. We got no sleep. We’re thirsty and we’re dehydrated, and now my

PLT

’s [pilot’s] gone blind.” Fortunately, Dick was able to read enough of the stuff, and I had memorized those maneuvers. That was part of the benefits of the delay of the launch was that it gave us more time to practice, and those maneuvers were intuitive to me at the time. They were just like they were bred into me.

As the reentry progressed, Engle recalled, it felt like everything went into slow motion as he waited to execute one maneuver after another. And then, with the winds having cooperated enough to prevent

Columbia

from having to divert to another site, it was time for the former

X

-15 pilot’s triumphant return to Edwards.

When we did get back over Edwards and lined up on the runway, as I mentioned before, I think one of the greatest feelings that I’ve had in the space program since I got here was rolling out on final and seeing the dry lake bed out there, because I’d spent so much time out there, and I dearly love Edwards and the people out there. In fact, I recall when Dick and I spent numerous weekends practicing landings at Edwards, I would go down to the flight line and talk with guys . . . and go up to the flight control tower and talk with the people up there, and we would laugh and joke with them. I remember the tower operator said, “Well, give me a call on final. I’ll clear you.” Of course, that was not a normal thing to do, because we were talking with the CapCom here at Houston throughout the flight. But I rolled out on final, and it was just kind of an instinctive thing. I called and I said, “Eddy Tower, it’s

Columbia

rolling out on high final. I’ll call the gear on the flare.” And he popped right back and just very professional voice, said, “Roger,

Columbia

, you’re cleared number one. Call your gear.” It caused some folks in Mission Control to ask, “Who was that? What was that other chatter on the channel?” because nobody else is supposed to be on. But to me it was really a neat thing, really a gratifying thing, and the guys in the tower, Edwards folks, just really loved it, to be part of it.

According to Engle, the landing was very much like his experiences with

Enterprise

during the approach and landing tests.

From an airplane-handling-qualities standpoint, I was very, very pushed to find any difference between

Enterprise

and the two orbital vehicles,

Columbia

and

Discovery

, other than the fact that

Enterprise

was much lighter weight and, therefore, performance-wise, you had to fly a steeper profile and the airspeed bled off quicker in the approach and landing. But as far as the response of the vehicle, the airplane was optimized to respond to what pilots tend to like in the way of vehicle response. . . . There were some things that would have been nice to have had different on the orbiter, . . . and that is the hand controller itself. It’s not optimized for landing a vehicle. It really is a derivative of the Apollo rotational hand controller, which was designed for and optimized for operation in space, and since that’s where the shuttle lives most of the time, it leans toward optimizing space operations, rendezvous and docking and those types of maneuvers.

Despite the change in schedule caused by the shortening of the mission, more than two hundred thousand people showed up to watch the landing. After the vehicle touched down, Engle conducted a traditional pilot’s inspection of his vehicle.

I think every pilot, out of just habit, gets out of his airplane and walks around it to give it a postflight check. It’s really required when you’re an operational pilot, and I think you’re curious just to make sure that the bird’s okay. And of course, after a reentry like that, you’re very curious to know what it looks like. You figure it’s got to look scorched after an entry like that, with all the heat and the fire that you saw during entry. Additionally, of course, we were interested at that time to see if the tiles were intact. . . . We lost a couple of tiles, as I recall, but they were not on the bottom surface. They had perfected the bonding on those tiles first, because they were the most critical, and they did a very good job on that. But we walked around, kicked the tires, did the regular pilot thing.

STS

-3

Crew: Commander Jack Lousma, Pilot Gordon Fullerton

Orbiter:

Columbia

Launched: 22 March 1982

Landed: 30 March 1982

Mission: Test of orbiter systems

The mission that flew after

STS

-2 could have been a very different one, had the shuttle been ready sooner or the sun been quieter, according to as

tronaut Fred Haise. The

Apollo 13

veteran had initially been named as commander of the mission, with Skylab II astronaut Jack Lousma as his pilot. The purpose of the mission would have been to revisit the Skylab space station, abandoned in orbit since its third and final crew departed in February 1974. At a minimum, the mission would have recovered a “time capsule” the final Skylab crew had left behind to study the effects of long-term exposure to the orbital environment. There were also discussions about using the shuttle mission to better prepare the aging Skylab for its eventual de-orbit. Unfortunately, delays with the shuttle pushed the mission backward, and an expansion of Earth’s atmosphere caused by higher than predicted solar activity pushed the end of Skylab forward. “And what happened, obviously was there was a miscalculation, I guess, on the solar effect on our atmosphere, which was raised, causing more drag,” Haise said. “So the Skylab [predicted time] for reentering was moving to the left in schedule, and our flight schedule was going to the right. So at a point, they crossed, and that mission went away.”

Haise and Lousma trained for several months for the mission, and when the Skylab rendezvous became impossible, Haise decided to reevaluate his future plans. Given his own experience and the number of newer astronauts still waiting for a flight, he decided to leave

NASA

and take a management position with Grumman Aerospace Corporation. “I just felt it was the right time to start my next career. And so I left the program in ’79 for that purpose.”

Haise’s departure meant changes for astronaut Gordon Fullerton, who recalled that at one point during shifting crew assignment discussions, he had actually been scheduled to fly with Haise on the second shuttle mission. “For a while I was going to fly with Fred. Then Fred decided he wasn’t going to stick it out,” Fullerton explained. “So then I ended with Vance [Brand] for a little while, and then finally with Jack Lousma, which was great. Jack’s a great guy, [a] very capable guy and a great guy to work with, and so I couldn’t have done better to have a partner to fly with.”

Recalled astronaut Pinky Nelson of the pair:

Jack and Gordo were black and white. I mean, they were the yin and yang of the space program, basically. Jack is your basic great pilot, kind of “Let’s go do this stuff,” and Gordo is probably the second-most-detail-oriented person I’ve ever seen. Gordo at least knew he was that way and had some perspective on it, but

there were things he could not let go. So he knew everything, basically. He knew all the details and really worked hard at making sure that everything was in place, while Jack looked after the big picture kind of stuff. They were a good team.

The shuttle was very much still a developmental vehicle when Lousma and Fullerton prepared for and flew

STS

-3. “When we flew

STS

-3, we had [a big book] called Program Notes, which were known flaws in the software,” Fullerton explained. “There was one subsystem that, when it was turned on, the feedback on the displays said ‘off,’ because they’d gotten the polarity wrong . . . which they knew and they knew how to fix it, but we didn’t fix it. We flew it that way, knowing that ‘off’ meant ‘on’ for this subsystem. The crew had to train and keep all this in mind, because to fix it means you’d have to revalidate the whole software load again, and there wasn’t time to do that.”

The big issue preventing the changes being made was time. The problems had been identified before the first launch, but continuing to work on them would have continued to delay the program. “They had to call a halt and live with some real things you wouldn’t live with if you’d bought a new car. That’s all part of the challenge and excitement and satisfaction that comes with being involved with something brand new.”