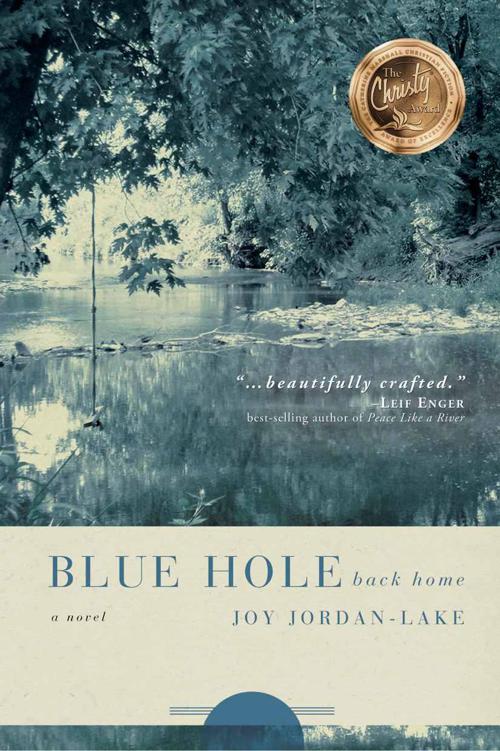

Blue Hole Back Home: A Novel

Read Blue Hole Back Home: A Novel Online

Authors: Joy Jordan-Lake

What people are saying about …

Blue Hole Back Home

“Reminiscent of

To Kill a Mockingbird, Blue Hole Back Home

is a haunting story, lyrically told, about the death of innocence under a Southern sun.”

Phyllis Tickle,

author and lecturer

“Though

Blue

Hole

Back

Home

is a coming-of-age story, it is also a surprising, moving, and fast-paced mystery. Joy Jordan-Lake has written a fine tale of racial conflict and healing, and she has done so with a fresh and engaging voice.”

Bret Lott,

author of

Jewel

and

A Song I Knew by Heart

“The first time I read a story by Joy Jordan-Lake, I knew this was what she was born to do. After reading

Blue Hole Back Home,

I’m more convinced than ever. Her beautiful language, rich characters, and careful attention to issues that really matter make her writing do what all good writing should: change us. Which is why I hope to be reading her work for a long time to come.”

Jo Kadlecek,

professor of creative writing at Gordon College and author of the Lightfoot Trilogy and

The Sound of My Voice

“As I read this novel, I was taken back to my childhood in Mississippi, and saw the manipulation of racism that had been pushed down in my memory. It helped me reflect on my past. I hope others will have a similar experience.”

John Perkins,

civil rights leader, author, founder of the Christian Community Development Association, and celebrated speaker on racial reconciliation

BLUE HOLE BACK HOME

Published by David C. Cook

4050 Lee Vance View

Colorado Springs, CO 80918 U.S.A.

David C. Cook Distribution Canada

55 Woodslee Avenue, Paris, Ontario, Canada N3L 3E5

David C. Cook U.K., Kingsway Communications

Eastbourne, East Sussex BN23 6NT, England

David C. Cook and the graphic circle C logo

are registered trademarks of Cook Communications Ministries.

All rights reserved. Except for brief excerpts for review purposes,

no part of this book may be reproduced or used in any form

without written permission from the publisher.

This story is a work of fiction. All characters and events are the product of the author’s imagination, although some are based on real-life events and people.

LCCN 2007941676

ISBN 978-1-4347-9993-7

eISBN 978-1-4347-6568-0

© 2008 Joy Jordan-Lake

The Team: Andrea Christian, Nicci Jordan Hubert, Jaci Schneider, Karen Athen

Cover/Interior Design: The DesignWorks Group

Cover Photo: © Flicker, Lori Smith

First Edition 2008

For

my husband, Todd Lake,

whose unflagging encouragement kept this novel alive,

and for

my brother, David Jordan,

who, at a time in my younger years when I had few friends of my own, shared his own friends with me

My love and thanks always

Acknowledgments

As always, I owe a thousand thank-yous to my husband, Todd Lake, and to my kids, Jasmine, Justin, and Julia Jordan-Lake, for their support, their love, their gracious tolerance of and laughter in the midst of nutty writing deadlines, and for all they teach me every day.

My parents, Diane and Monty Jordan, my brother, David Jordan, and his wife, Beth Jackson-Jordan, their kids, Christopher, Catherine, and Olivia, my mother-in-law, Gina Lake, and brother-in-law, Steven, have been thoughtful encouragers, sometimes in a well-timed word or hug, sometimes in the gift of an obscure and incredibly relevant book.

A circle of far-flung but always-dear friends offered enthusiasm, comfort, and reminders to laugh at myself at every turn. Susan Bahner Lancaster, my childhood chum, fellow English professor, and lover of books, read this novel in its earliest stages and offered invaluable insights. The unsinkable Kelly Shushok would not rest until this book was published. Throughout every book deadline, Ginger Brasher-Cunningham has called with a word of grace or good humor just when I needed it most. Laura Singleton, herself a writer, has been an inspiration and encourager for years. The multitalented Milton Brasher-Cunningham has been there—if a thousand miles away—to share the writing life, help celebrate good news, and help mourn the bad. Susan and Kyle Matthews and their kids have been cherished companions for my family and me as we’ve thought and dreamed together about faith and words and music. It was their son Christopher who reminded me how much I loved Earth, Wind & Fire, and still do.

I am so grateful, too, for the writing-specific encouragement and good counsel of Tammy Bullock, Kitty Freeman Gay, Mike Glenn, Regina and Bryan Hall, Elizabeth and Scott Harris, Kelly Monroe Kullberg, Anne Moore, Julie Pennington-Russell, Dorrie and Ramon Presson, Elizabeth and Jason Rogers, Mary Anne and Roger Severino, Christy and Jim Somerville, Susanne Starr, Benita Walker, Gloria White-Hammond and Ray Hammond, and a host of others I’ll hate myself in the morning for not specifically naming.

I also wish to thank Katie Boyle of Veritas Literary Agency and the good people of David C. Cook who made this book such a pleasure to publish: my particular gratitude to Don Pape, Andrea Christian, and their fabulous gun-for-hire, Nicci Jordan Hubert. If this novel has any merit, it’s thanks to Nicci’s heart and instincts for the rhythm of story.

And finally, I’m thankful for the kindhearted people of my hometown, Signal Mountain, Tennessee, who are, by the way, not the same as the people of the fictional Pisgah Ridge. The people of Signal Mountain taught me my earliest lessons on faith and risk and redemption, and I am indebted to them for not giving up on someone so painfully shy and homely.

1

Backstitching Time

Likely it was only two dreams crisscrossing paths, one snagging on the other in passing, but somehow the face that walked by me this morning, not four feet away, got tangled up with one from my past. The way-back and way-faraway, all quiet and almost forgotten, got yanked up and placed alongside today, where two minutes before I’d have told you I was: in Boston. At the Public Garden. Not a stone’s throw from Beacon Hill, where I live and work, and pay as much for my own private parking space as folks back home do for a decent slab ranch and enough acres for the dogs to tree themselves something other than city-soft squirrel.

I was cozied up on a park bench in the Garden to cool my espresso and pry off the pumps I despise and I wear every day. Then the face passed by my bench. I lurched forward to stare, then back—to cover for staring—and splashed espresso clear down my front.

And I swear time backstitched on itself, and at that very moment, I was barefoot—not with black pumps stowed under a park bench, but the right kind of barefoot. The kind of barefoot that went with the truck bed of a pickup. I was back with the wind standing my ponytail straight up over my head, the Blue Hole just around the next curve. And I was tracing my cheek where a kiss had just landed.

So there I sat in the garden this morning, tracing my cheek, feeling my heart seize up in my chest, and the ache stabbing down to my toes, and my toes going cold in the wind off the truck. In that moment, the smell of espresso got overpowered by the scents of my past: pine needles and boy-sweat, salted peanuts and Coke. I heard bluegrass guitar and banjo all mixed up with rhythm and blues and a rope swing ticking forward and back, keeping time. I was barefoot in the back of a pickup, believing that it was love that makes people brave and gorgeous and clever and kind. Believing, and being wrong.

I haven’t often—or ever, actually—told the story of that summer, because its beginning, when the new girl lifted her brown legs up over our tailgate, never connected up with the end, with the goodness or the fire. Brown was what that leg was, back at the beginning, and not just tanned into dark. It was me who’d said we should stop for her, and me who knew first that our troubles had just dug in deep, a fat tick way down into fur.

“Shoulda known better” was what people said. “You mix up your colors like ’at and you got yourself mud’s what you got.”

Thing was, I

did

know better. Brought up in those mountains where the pines grew tall out of clay the color of blood, I knew what was what, and who was who, and who was not.

Plenty of folks said what happened that summer was my doing, and plenty said it was all Jimbo’s fault. But I’m saying it was the fault of the Blue Hole.

“All sunk sweet and sacred” was what Jimbo called the Blue Hole back then.

The son of the First Baptist Church preacher—a kind of Little League pope in a small Southern town—Jimbo handled words like electrical wires he just might dip into water. And though he favored the peculiar or crude, he’d often come out with something like that—some musty old word like

sacred

—and make us all jump.

Sacred’s not a word I’ve ever much liked—says to me bad organ music, the celesta stop out, and sopranos with skin like cheap parlor drapes hung from their jaws. But maybe some things, and some places, just are. And maybe the Blue Hole was one of those places. Even more so, perhaps, after that one August night when men in white bedsheets paid house calls all over Pisgah Ridge, and made sure we all understood that although times had supposedly changed, some kinds of thinking, and some kinds of hate, had not. It was the men in white bedsheets that changed us—them and the Blue Hole changed us forever.

I’ve learned, now, not to speak of these things to folks here in Boston, especially the men that I date. Early on, before I’d learned better than to talk of back home, they would fumble their lobster forks into their chowder. “How

old

must you be?” they would ask—the ones whose mommas must not have harped much on manners. Like living through one race of people not being real kind to another takes a whole lot of age. Sometimes inside the main course, I might try to explain George Wallace, the before and the after repentance—was that what he called it?—and Reconstruction and Rosewood. Then they had to know why, did I think, Huey Long got himself shot and Strom Thurmond didn’t.

“Pass the drawn butter please, sugar” is how I come back.

So I generally don’t talk much of the past anymore, my own or the South’s. I don’t stamp myself with stories that might limit my shelf life, making me sound even older than these Boston winters already have made me look. I rarely refer to Carolina at all, or to the mountains, or to my little town on the Ridge. If I mention the Blue Hole, it’s only in passing, and I take care to skirt real far around the topic of riots and rope swings. I skirt further still around the story of Jimbo and us and the new girl who tore up our calm, or the good that snuck up on us in the dark. I don’t mention crosses, either burning or strung up by the neck in a church. I don’t mention Mecca or Jesus, or why just yesterday driving the Pike, when Daniel Shore on NPR said “Sri Lanka,” I let go the wheel and made a map with my hands, just like I have now for twenty-five years, every time I hear the country’s name spoken.

They all—these men who buy me dinner at Legal’s—once read O’Connor and Tennessee Williams and Faulkner at Harvard. That was years ago now, back before their first marriages—but it’s clear they’ve looked ever since for Misfits and Snopses and Stellas, for lovely, loose women who smell of magnolias.

I don’t line out for these men, or for anyone else, why my adult life takes place a good thousand miles from the only place I’ll ever call home, or how no manner of grace—a word Jimbo used—can undo what gets done. I don’t say this either: that my home is a beautiful place, a terribly beautiful place that gives birth to traitors and cowards and heroes, sometimes all in one skin. And I never say why—because I don’t know—I long like I do to go back.

They say you can’t go home again, ever, can’t relive the past—and until this morning I would have said that was true. But something about the face I saw in the garden got me to wonder if maybe time does have its backstitches and snags like the physics professors all drone on about, though no one believes them. Maybe some parts of your past don’t stay just where you thought your life left them all shredded in pieces.

This morning I wondered, nearly knocked to my knees with the scent of espresso and pine needles and peanuts and sweat all at the same time, if maybe there’s some other end to my story still to get made.

_________

In that summer of 1979, we all ran together in a mangy pack—that’s what Jimbo’s mother called us,

y’all’s mangy pack

, and she liked us better than most. My brother Emerson and his best friend, Jimbo, had started their landscaping business—their work always centered on Miss Mollybird Pittman’s impossible yard—and I helped out some when Momma allowed. It was the summer when everyone else bought albums and ’45s of the Bee Gees and Eagles and Peter Frampton, but Emerson’s white pickup truck held only an eight-track tape player, which soundtracked our shoveling and planting and hauling manure. The only tapes the three of us owned came from Jimbo’s purchase at a garage sale down in the valley where a woman was unloading her entire eight-track collection, the tapes’ slick paper labels already bubbled. Jimbo loved his collection, and we loved Jimbo, so we labored under a Southern Appalachian sun to decade-old Motown. Diana Ross and Marvin Gaye oversaw our planting magnolias; James Brown set the beat for our sinking azaleas into peat moss and mulch.

That summer the temperatures soared, even up on our mountain, and stayed there—and I, ever since I’d studied Icarus that spring at school, was sure we’d all just melt and plummet on down to the valley.

“If I keep sweatin’ like this,” Jimbo would moan every morning while he flopped himself into Emerson’s truck bed, “y’all gonna have to call me a lifeguard.” Or sometimes, “Can’t hardly stand to strap on underwear.”

“Gave it up yesterday myself,” Emerson would tell him, or “I’m saying we give up the pants, too”—which was likely why my momma didn’t much like my going along.

We survived the heat that summer by piling into Emerson’s pickup and heading into the woods. We carted along a cast-off Styrofoam cooler pieced back together with electrical tape, and Emerson’s Big Dog, a remarkably chubby golden retriever with a weakness for pork barbecue scraps and Dr Pepper, which she drank straight from the can. Jimbo was learning to play Em’s guitar, and from the truck bed, he fingered out strange medleys of “Stairway to Heaven” and “Holy, Holy, Holy.” In four-wheel drive, we jolted down old logging trails—Jimbo fumbling chords as we went—through tangles of loblolly pines and post oaks that hid the secret we teenagers had found—or maybe created. They were deeply eroded, those old logging trails, ragged gashes in that dark red clay, like a knife had gone slashing through flesh.

“You comin’, Turtle?” Jimbo’d call from the truck, Emerson slowing enough for me to fling myself in over its side. My parents christened me Shelby Lenoir. Shelby Lenoir Maynard—not too bad as Southern names go—but it was Jimbo’s nicknaming me “Turtle” that stuck. Back when we were kids lined up on the vinyl bench seat of our father’s Chevy Impala, I’d taken my turn steering the car on a two-lane dirt road. Jimbo and Em, in giggle-fits over my barely keeping the car out of the woods, had first seen the truck coming our way and, laughing too hard to speak, only pointed, while my father, beside me, gave the order to straighten the wheel. Instead, I’d covered my face with both arms. My new name was born that very day, along with the sad realization I live with even now here in Boston that sometimes when life barrels at me head-on, I hide my head and hope the crash doesn’t land on my own little shell.

I had no female friends in those days: Girls struck me as backstabbing and shallow and silly, compared with the brutal, straight-in-front put-downs of my brother and his buddies. I never much fit in with the girls’ fingernail-polishing parties. I was skinny and awkward, and carried whatever smarts I had then like a warning, like a Jew’s yellow star, or a leper girl ringing her bell. It was the smarts, Emerson said, that messed me up most—as a girl, I reckon he meant.

The new girl in town might have counted as my one female friend. Except that she didn’t count. She’d come just the last month of school. I was a sophomore—Jimbo and Em, loud, cocky juniors—and the new girl and I had met, briefly, after nearly colliding in front of the water fountain down by the old gym.

Naturally I knew who she was, her being the only one in our school even close to her color—though I can’t say I knew anyone who’d spoken with her. At the fountain, the new girl motioned for me to drink first.

“Before me, you may proceed,” she told me, and nodded her head real formal.

“No, really, you go ahead.”

“Please, I insist upon it.” She stepped aside, and held out her hand to me, like we were both there on business. “If I may present myself, I am Farsanna Moulavi.”

I’d heard people say she was strange—more than her color, I mean—and just that one stiff, stilted speech was enough to make me wonder if people weren’t right. And her face was odd too—her expression, that is. Because—and here was the thing—there wasn’t any expression at all. Except in her eyes. And they looked out of her paralyzed face a little too dark, a little too deep, maybe a little unsteady, like they were black pits that might or might not be hiding explosives.

“Shelby Lenoir,” I told her. “I’m Shelby Lenoir Maynard.” And I almost added, “There’s some call me Turtle.” But that was reserved for friends.

I drank, and to cover for the water dribbling down my chin, said the first thing that poked into my mind: “Cool accent.”

“The accent is to you the strange thing, no?” She asked this with an almost-smile, some kind of not-smile hanging at the edges like shadows.

“Well … your skin’s a nice color,” I told her then because it was true—though it sounded peculiar somehow, saying it out loud to her face.

Farsanna Moulavi was the color of the hot cocoa Jimbo Riggs’ mother made from Nestlé dark chocolate, powdered sugar, and dried milk. The kind the Riggses drank in their basement rec room when they played Parcheesi on Friday nights.

“I come from Sri Lanka,” she said, watching me. “You perhaps know it as the former Ceylon.” She held up her right hand flat against the air, as if it were a map. “If this would be India, then this,” she placed her left fist by the lower thumb knuckle of her right hand, “is Sri Lanka.” She turned to drink, then rose up straight, all in one piece, like her spine didn’t bend. “The accent and the skin, they come both from Sri Lanka.”

“Sri Lanka.” I nodded to show I’d recognized the map she could make with her hands, and that I knew where it was—close enough, anyhow. My father was the city desk editor of our local newspaper and he was a Yankee, so he likely knew all about Sri Lanka, or would sound like he did anyway—which, I’ve learned by living in Boston, is pretty much the same thing.

Now Momma, had she been there with the new girl at the fountain, would’ve offered up quick something sweet—maybe a second cousin’s having seen that part of the world lately and loved it. Just loved it. Momma made certain everyone in her path felt affirmed at all times, even if she had to perjure herself, or her second cousin, to do it.