Blue Highways (42 page)

Authors: William Least Heat-Moon

“Well, then,” Bakke said and buried me in quotation. I had fired my single salvo but hadn’t sunk him.

“When the Bible has so many interpretations, how do you know your view is right?”

“I don’t interpret. I read the Word as it is and trust the Lord to make me understand. And another thing: understanding depends on how well you know the whole Bible and how the parts fit in.”

“You seem to know all the Bible well.”

“I know the New Testament better than the Old. I read four Old Testament chapters and four New Testament chapters six days a week, so I get through the whole Bible about twice a year. But the New Testament is less than a third as long so I get through it more often.” Bakke turned toward me. “I saw you reading this morning. Was it the Bible?”

“The journals of Lewis and Clark. Lewis was recounting his thirty-first birthday, which he spent not far from here. He surveyed his life and found he’d done very little with it. He vowed right then to live for others the way he had been living for himself.”

“Some worldly books have the Spirit moving in them.”

We rode silently for several miles, and Bakke dozed off. A bird swooped the highway and slammed into the hood. The clunk woke him. “What was that?”

“I hit a bird.”

“Why are you stopping?”

“Want to see what kind of bird it is. Or was.”

He got out too. I picked it up, a warm crumpled fluff limp in my hand, its talons clenched into tiny fists. “A sparrow hawk,” I said.

“Throw it away.”

“‘There is no object so soft but what it makes a hub for the wheeled universe.’ The poet, Walt Whitman, said that.”

Bakke smiled. We drove on along the Kootenai River, and he pointed out places that would be certain death if you slid off the pavement.

“I want to ask you something personal,” I said. “Everything you own—other than your testimonies and typing paper—is in that aluminum suitcase?” He nodded. “Would you show me what’s in there? I’m interested in how you’ve reduced your goods to that box.”

“Never call them ‘goods.’” He opened the little case and held up the contents one by one: two shirts, a pair of pants, underwear, toothbrush and paste, bar of soap, flashlight, candle, toilet paper, a corn muffin, and a bag of Jolly Time popcorn. “I try to ‘live of the gospel,’ as Paul says.”

“I envy your simplicity.”

“Paul says, ‘Set your affection on things above, not on things on the earth.’ Colossians three:two. The idea is to come away from things, away from ourselves, come away from it all toward God. Buying things is an escape. It’s showing what you aren’t. It’s loving yourself.”

I was still looking at the suitcase. “You’ve got necessities in one box, your work in a briefcase, a creed in your shirt pocket. I admire the compression of it. I wish I could reduce it all to a couple of boxes. I like your self-sufficiency.”

“Don’t give me so much credit. Paul preached how pride separates us from God.” He opened his small Bible and read: “‘Walk not as other Gentiles walk, in the vanity of their mind, having the understanding darkened, being alienated from the life of God through the ignorance that is in them, because of the blindness in their heart.’ Ephesians four:seventeen.”

“Maybe so, but for basic necessity, you come close to material self-sufficiency.” Bakke sat quietly. “The college students you talk to, they must admire your on-the-road work, your freedom.”

“I don’t think many would trade places with me. Would you?”

It was a terrible question.

“I don’t have your belief or purpose. But I wish I knew what you know.”

“‘Knowledge puffeth up, but charity edifieth. If any man think that he knoweth any thing, he knoweth nothing yet as he ought to know.’ First Corinthians eight: one and two. Knowledge of the Lord is the knowledge worth knowing.”

“Walt Whitman says, ‘Be not curious about God, for I who am curious about each day am not curious about God.’” Bakke smiled again. “Now you’re going to say mortal life is a troublous shadow, aren’t you?”

“‘For what is your life? It is even a vapor, that appeaseth for a little time, and then vanisheth away.’ James four:fourteen.”

“I like little appeasing vapors.”

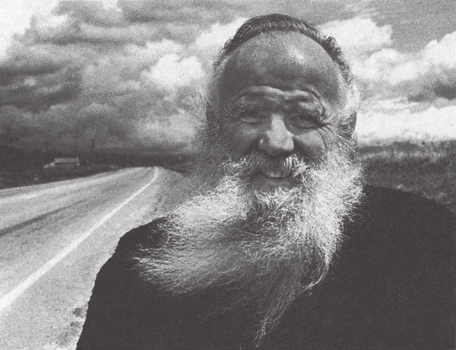

16. Arthur O. Bakke outside Kalispell, Montana

“‘Let no man deceive himself. For the wisdom of this world is foolishness with God.’ First Corinthians three: eighteen and nineteen.”

“‘Why should I wish to see God better than this day?’ Whitman, ‘Song of Myself.’ Here’s another one from a Sioux medicine man called Black Elk: ‘

Whatever

you have seen, maybe it is for the good of the people you have seen it.’”

“Errors. To know God, to know the City of God—that’s the only true life.”

“Maybe this is the City of God.”

“How could it be? The City of God has streets paved with transparent gold.”

“Sounds pretty worldly. That’s the standard account in Revelation, isn’t it?”

“Yes, Revelation.”

We rode on in silence to Kalispell, and Bakke dozed off again. I looked at him. He seemed one of those men who wander all their lives. In him was something restless and unsatisfied and ancient. He was going everywhere, anywhere, nowhere. He belonged to no place and was at home anyplace. He understood that the Bible, in spite of its light, isn’t a particularly cheerful book, but rather one with much darkness, and he recognized that is where its power comes from.

Yet the word he carried to me wasn’t of the City of God; it was of simplicity, spareness, courage, directness, trust, and “charity” in Paul’s sense. He lived clean: mind, body, way of life. Hegel believed that freedom is knowledge of one’s necessity, and Arthur O. Bakke, I.M.V., was a free man hindered only by his love and conviction. And that was just as he wanted it. I don’t know whether he had been chosen to beat the highways and hedges, but clearly

he

had chosen to. Despite doctrinal differences, he reminded me of a Trappist monk or a Hopi shaman. I liked Arthur. I liked him very much.

Near Kalispell he woke up. I said, “I’ll let you off at the junction of ninety-three so you can hitch toward Missoula.”

“I could ride on with you. I know a friend in North Dakota.”

“I’ve got to go alone, Arthur. For now, I have to go by myself. There’ll be times when I’ll wish for your company.”

He hobbled out and came around to my window as gusts again pulled his beard sharply. We shook hands, and he said, “Carry God’s blessing, brother.”

“You’ll be all right in this wind?”

“‘For I have learned, in whatever state I am, therewith to be content.’ Phillippians four:eleven. Hardships are good. They prepare a man.”

“I believe you.”

T

HE

boy was severely handicapped. Trying to fill a big thermos from a spring spewing out of the mountain east of Kalispell, near Hungry Horse, he laughed as the cold water splattered him, and he burbled something.

I had no idea what he said. “Very cold water indeed,” I answered.

He burbled again, then lost his footing, and fell hard on the wet rocks. The gush hit the flask and kicked it away. I went to help him.

“Leave him alone!” someone shouted over the crash of water. A man who looked as if he’d swallowed a nail keg came toward us. “Let

him

do it. You’ll make him weak if you do it for him. He’s my son. He understands.”

The boy struggled up and slipped and struggled again.

“I’ll hand him the thermos.”

“Let him get it.” The boy retrieved the jug and went back to the big spout. He fell again, got up, and tried again.

“Grab on to the pipe!” I shouted, but he couldn’t do it and hold the jug. The thermos bounced over to me. I picked it up and handed it to him.

“He’ll never survive if he gets turned into a pussy,” the father said.

“He’ll never survive if he dies filling a thermos jug.”

“Malarkey! We’re on our way now to float a branch of the Flathead. That river’s a bad-tempered horse, and you’d better stay on top of it, or it’ll beat your liver out. This little gimp’s got more white-water time than most of those canoe daredevils, and he can’t even swim. Just never learned fear.”

The boy succeeded in filling the jug. I filled mine and drank off a pint. My teeth ached from the cold, and I grimaced. The boy watched and did the same thing, but his grimace was too real.

“Glory is that cold!” I said to him. “And good!”

“Golden gud!” he repeated.

The father stepped in to fill a jug. “On our way home,” he said with authority, “I’ll fill a five-gallon can. I’ll tell you something. I used to go through sixty suppositories a month—two a day. Last year, I started mixing this water with a teaspoon of cayenne and equal parts of nutmeg and flour. Now I don’t even use six tablets a month.”

“You attribute healing power to this water?”

“Water’s got nothing to do with it. It’s the cayenne, nutmeg, and flour.”

“That’s different.”

“Nobody believes me. If you ever get hemorrhoids, try it, and don’t worry about thanking me. I never could thank the old boy I got it from.”

Eastward: U.S. 2 up the long canyon of the Middle Fork of the Flathead River. To the north, gusts scoured gritty snow from one wind-shorn peak to another: Mount Despair, Mount Rampage, Mount Scalplock, Mount Doody. In a crevasse I stopped to watch six mountain goats cling to the canyon wall. The mountain goat isn’t a goat at all, but rather a relative of the antelope, and one proved it by bounding ledge to ledge, each time sticking like an arrow.

The highway ascended the west slope of the Continental Divide. In the middle of the pavement at the top of Marias Pass stood a tall limestone obelisk marking the divide and also commemorating Teddy Roosevelt. Your basic double-duty monument. Then the great mountains of the west lay behind, and, sweeping ahead, mile after terribly visible mile of roadway across a grandly canceled plateau, were the grasslands of the Big Sky country.

The state of Montana had marked spots of fatal car crashes with small, pole-mounted steel crosses: one cross for every death. Along the highway, as it traversed the Blackfeet reservation, the little white crosses piled up like tumbleweed: a single, a pair, a triple, a half dozen, a group of nine. What began as an automobile safety campaign, the Blackfoot—once among the best of Indian horsemen—had turned into roadside shrines by wiring on plastic flowers. Somebody later told me the abundance of crosses around the reservation was “proof” of chronic alcoholism.

The reservation town of Browning, unlike Hopi or Navajo settlements, was pure U.S.A.: an old hamburger stand of poured concrete in the shape of a tepee but now replaced by the Whoopie Burger drive-in, the Warbonnet Lodge motel, a Radio Shack, a Tastee-Freez. East of town I read a historical marker that said the Blackfeet had “jealously preserved their tribal customs and traditions.” Render therefore unto Caucasians the things which be Caucasian.

At Cut Bank, the rangeland and wheat fields and oil wells began. Montanans call U.S. 2, paralleling the Canadian border all the way to Lake Huron, the “High-line.” The most desolate of the great east-west routes, it was two lanes of patched, broken, rutted, mind-numbing pavement running from horizon to horizon over the land of god-awful distance.

I stopped at Shelby. Shelby used to be on the old Whoop-up Trail, a route followed by Missouri River whiskey traders who sold to Indians. What the U.S. Army could not accomplish—the destruction of tribal organization—whiskey traders did with help from Christian missionaries who suppressed the old rituals. The white settlers, moving in after tribal disintegration opened this land, should have erected a monument to the whiskey bottle. The Blackfoot, for example, once hunted an area about twice the size of Montana; now their reservation of steel crosses and Whoopie Burgers doesn’t occupy even all of Glacier County. It isn’t that Indians lost their land because of whiskey—that stuff they called the Great Father’s Milk—they just lost it faster because of whiskey.

The Husky Cafe truck stop, glowing warm in the spring wind, was one of those places with a rack of joke postcards about fishing weekends, outhouses, mule cruppers (“I’m the one on the left”), and full-color photographs of spotted fawns and antlered jackrabbits. At the counter and tables sat the diesel boys in their adjustable, ventilated caps that said

MACK, GMC, KENWORTH, WHITE

.

I seldom go into truck stops. When I hear teamster cant about being the self-professed “son-of-a-bitches of the highway,” when I hear stories of retreads shredding at seventy, when I watch drivers trying to recuperate on coffee and chili, and look at faces with eyes bloodshot from “pocket-rockets,” and witness their ludicrous attempts to be folk heroes, I get very nervous the next time I see one pushing forty tons seventy miles an hour at me. But that night in Shelby, I didn’t have much choice.

One eighteen-wheel stud said to the waitress, “Hun, you know, don’t cha, that old truckers never die—they just get a new Peterbilt.”

“I’ve heard that about a goddamn million times.” She had the skin of a Dresden figurine and the mouth of a Fruehauf driver. “They say the drive in your shaft’s about shot.” Automatically she pushed a mug of coffee under my menu. “What’s it for you, hoss?” Someone cracked another joke at her. Looking at me, answering him, she said, “Teach your old lady to suck eggs.”