Blue Highways (14 page)

Authors: William Least Heat-Moon

“I’ve forgotten most of it now. Words I remember are pictorial signs. Here, what am I saying?” His right fingers wiggled over his left palm.

“Run up the hill and get a pail of water.”

“No, no. ‘The dog chased the cat into the church.’”

“I think you misspelled

dog

. It has four thumb wiggles, not two. Any complexity of thought, I take it, had to occur between man and God rather than between monks.”

“Maybe. But you just don’t talk as much if you have to use fingers. We don’t waste words today. In the refectory, for instance, we still observe to a degree a monastic silence. But now, as we eat, a brother will read to us.”

“Scripture and Biblical commentary? Things like the Holy Fathers?”

“We just finished

Nicholas and Alexandra

. We began

Understanding Media

not long ago but voted it out. We vote on books to be read, then vote again one-third and two-thirds of the way through to see if we’re interested in continuing. Had trouble understanding McLuhan.”

As we walked the grounds, Father Anthony introduced the monks. They were friendly in a plain and open manner, unsanctimonious, and not outwardly pious. They did not, as Whitman says, “make me sick discussing their duty to God”; neither were they, to use Merton’s word, “disinfected” men. Yet the older ones appeared a decade or more younger than men of their ages I was accustomed to seeing. Twisted or hanging faces were few. And, I must say, there was a life, a spirit, in the old who moved slowly. I realized I was trying to catch in their faces something I wouldn’t see outside the walls—something hidden, transcendental, even mystical. But I noticed only a quietude, and I felt that more than saw it.

I asked to see a dormitory. He didn’t answer immediately. Instead he picked up a leaf and twirled it. “Nothing’s secret about the rooms, but some brothers don’t want disturbance. The opportunity for uninterrupted devotion and reflection is the reason many come here.

Monastic

means ‘living alone.’” He was almost apologetic. “The brothers you’ve met are ones whose duties put them before visitors. But others prefer solitude. One lives alone in the woods. It’s his choice. A few still keep the rule of silence. You must understand the importance of quiet to us.”

“A noisy man doesn’t hear God?”

“I wouldn’t presume to answer that.”

“There is something else then—something I’d like if it’s permitted.”

“We don’t copy manuscripts by hand.”

“I know—you’ve got a brother who repairs Xerox machines. No, that’s not it. I’d like to talk with a brother about why he became a monk. You must get tired of the question, but still, I’d like to ask again.”

“Are you staying the night?”

“Never crossed my mind.”

“After dinner, I’ll try to send someone around. Won’t be easy.”

The evening meal was vegetable soup, peas, rice, bread, vanilla pudding. Again, just enough. At the table, talk turned toward a Savannah visitor recuperating from a coronary bypass who had come to see his novitiate son. Although the conversation was alternately serious and jocular, the man’s quiet presence, the impending farewell between father and son, touched us all. Once more the silent tolling. This time I rose with them.

Father Anthony asked me to join him at vespers. On the way to the chapel, we didn’t talk. I think he was preparing. I remembered my denim and suspenders. “My clothes,” I said.

He didn’t break stride or turn his head. “How could that matter? But singing on key does. Can you?”

“Never could.”

“Don’t sing loud then. God doesn’t mind. I do.”

The monks filed noiselessly into the great, open sanctum and sat facing each other from both sides of the choir. At a signal I didn’t perceive, they all stood to begin the antiphonal chanting of plainsong. Only younger ones and I looked at the hymnals. The sixty-five monks filled the church with a fine and deep tone of the cantus planus, and the setting sun warmed the stained glass. It could have been the year 1278.

I looked at the faces. Quietude. What burned in those men that didn’t burn in me? A difference of focus or something outside me? A lack or too much of something? To my right a monk sat transfixed, eyes unblinking, and his lips, the tiniest I’d ever seen on a man, never moved. I thought if I could know where he was, then I would know this place.

There was nothing but song and silences. No sermon, no promise of salvation, no threat of damnation, no exhortation to better conduct. I’m not an authority, God knows, but if there is a way to talk into the Great Primal Ears—if Ears there be—music and silence must be the best way.

Afterwards, I returned to the balcony. Empty but for the sounds of dusk coming on: tree frogs, whippoorwills, crickets. I’ve read that Hindus count three hundred thirty million gods. Their point isn’t the accuracy of the count but rather the multiplicity of the godhead. That night, if you listened, it seemed everywhere. I sat staring and felt “strong upon me,” as Whitman has it, “the life that does not exhibit itself.” Someone behind, someone tall, said my name.

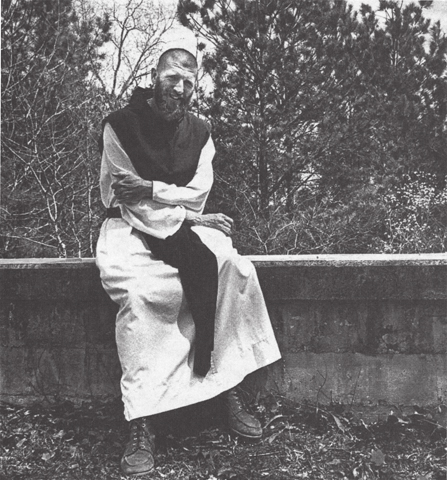

H

E

used to be Patrolman Patrick Duffy. Now he was usually just Brother Patrick. A name didn’t count for much anyway. Angular, sinewy, red beard, shaved head, white tunic. Distinctly medieval in spite of the waffle-soled hiking boots. About him was an unacademic, unpietistic energy—the kind that the men who made Christianity must have possessed. Quite capable of driving snakes out of Ireland, or anywhere else for that matter.

“I hear you have questions,” he said. None of the usual feeling out before a conversation on a sensitive topic begins. A frontal assault man.

I picked it up. “Tell me why a man becomes a Trappist monk. Answers I heard today sounded like catechism recited a thousand times.”

“It isn’t an easy question—or at least the answer isn’t easy.”

“Tell me how it happened to you. How you got here.”

“I’ve been here five years. I was a policeman in Brooklyn—Bedford-Stuyvesant. On my way to becoming a ghetto cop. Did it for seven years. Before that, I was an Army medic. Attended St. Francis College part-time and worked in the Brooklyn Public Library. And education has come in other ways too. I hitched around the country in nineteen fifty-seven and again in ’fifty-eight. Went to Central America on the second trip and spent time in Honduras.”

“Jack Kerouac?

On the Road

?”

“Something like that. I came back to New York and worked as a sandhog digging subway tunnels in Manhattan. Then I got seaman’s papers to go into the merchant marine—listen, papers are hard to come by. I had to scramble to get them, then I never used them.”

“Why not?”

“Got interested in police work, but I was still unsettled and afraid of getting stuck on a ship. Afraid of drudgery. I like changes.”

“Changes? In here? Of all you could find here, I’d think change would be the least likely.”

“I mean growth and a change of pace. I work four hours as an electrician’s assistant. Watch out, this is going to be philosophical, but you could make some kind of analogy between being an electrician and a monk—the flow of energy from a greater source to smaller outlets. Still, the electrical work is different from the spiritual work, even if I try to merge them.”

“Two things don’t seem like much change.”

“I’m also what you might describe as the monastery forest ranger. They call me Smokey the Monk. I oversee the wooded part of the grounds. Try to keep the forest healthy. Just for fun, I’ve been cataloging all the wildflowers here. We’ve identified about two hundred species, not counting the blue unknowns and pink mysteries. Working on shrubs now. And I’ve taken to bird-watching since I came. I spend a lot of time in the woods reading, thinking. That’s when real changes can happen.”

“What do you read?”

“In the woods, some natural history, some Thoreau. Always scripture and theology. Reading about the charismatic movement now.” He was silent a moment. “Does any of this explain why I’m here?”

“It all must be part of an answer.”

“For years I’ve been fascinated by intense spiritual experiences of one kind and another. When I was seventeen—I’m forty-two now—I thought about becoming a monk. I’m not sure why, other than to say I felt an incompleteness in myself. But after a while, the desire seemed to disappear. That’s when I started traveling. I learned to travel, then traveled to learn. Later, when I was riding a radio car in Brooklyn, I began to want a life—and morality—based not so much on constraint but on aspiration toward a deeper spiritual life. Damn, that was unsettling. I thought about seeing a psychiatrist, but after a couple of months, I just stopped worrying whether I was crazy.”

“What happened?”

“I’m not sure. Maybe I got cured when I started working part-time with the Franciscans in New York. They do a lot of community work at the street level, and that gave me a chance to look into this ‘monkey business,’ as a friend calls it. I joined the Franciscans Third Order for two years, to test whether I really wanted to enter a monastery, although their work is secular rather than monastic. Then I worked with the Little Brothers of the Gospel. They live communally, in stark simplicity, in the Bowery. That helped make up my mind. I liked what I could see of a religious life. I began to see my problem was not trusting myself—being afraid of what I really wanted.”

He pulled up his tunic and scratched his leg. “Understand, there was nothing wrong with riding a radio car, although I got tired of the bleeding and the shot and cut people I was bandaging up. Seemed I was a medic again. And delivering babies in police car backseats. Thirteen of those. The poor tend to wait to the last minute, then they call the police.” He stopped. “Forgot what I was talking about.”

“Trusting yourself.”

“Better to say a lack of self-trust. As a kid, I was always searching for something beyond myself, something to bring harmony and make sense of things. Whatever my understanding of that something is, I think it began in the cop work and even more when I was assisting the friars in New York. I was moving away from things and myself, toward concerns bigger than me and my problems, but I didn’t really find a harmony until I came here. I don’t mean to imply I have total and everlasting harmony; I’m just saying I feel it more here than in other places.”

He was quiet for some time. “Tonight I can give you ten reasons why I’m a monk. Tomorrow I might see ten new ones. I don’t have a single unchanging answer. Hope that doesn’t disappoint you.”

“Try it in terms of what you like about the life here.”

“I’ve always been attracted to hermitic living—I didn’t say ‘hermetic living’—but only for short periods. I go off in the woods alone, but I come back. Here, nobody asks, ‘What happened to you? You off the beam again?’ Living behind that front wall—it doesn’t surround us, by the way—living here doesn’t mean getting sealed off. This is no vacuum. We had a new kid come in. He left before he took his vows because he couldn’t find so-called stability—stability meaning ‘no change.’ I told him this place was alive. People grow here. The brothers are likely to start sprouting leaves and blossoms. This is no place to escape from what you are because you’re still yourself. In fact, personal problems are prone to get bigger here. Our close community and reflective life tend to magnify them.”

6. Brother Patrick Duffy at the monastery near Conyers, Georgia

“How did you finally make the decision to ‘come aside’?”

“A friend’s father told me, ‘If you don’t do what you want when you’re young, you’ll never do it.’ So I quit waiting for certainty to come.”

“A five-year experiment. Was it the right thing?”

“Right? It’s

one

of the right things. The

best

right thing. I believe in it enough I’m taking my permanent vows in October.”

“You don’t have second thoughts?”

“Second, third, fourth. I go with as much as I can understand. And I’ve gotten little signs. Like listening to Beethoven. I loved Beethoven. Been here two years, and one day I just went over and turned the stereo off. Beethoven was too complex, I guess, for me. My tastes have developed toward simpler things. Merton calls it ‘the grace of simplicity.’ Haven’t broken myself of Vivaldi though.”

I wanted to ask a question, but it seemed out of bounds. I decided to anyway. “I’d like to know something, partly out of curiosity and partly out of trying to imagine myself a monk.” He didn’t laugh but I did. “My question, let’s see, I guess I want to know how you endure without women.”

“I don’t ‘endure’ it. I choose it.” He was silent again. “Sometimes, when I’m doing my Smokey duties, I come across a couple picnicking, fooling around. Whenever that happens, when I’m reminded where I’ve been, I sink a little. I feel an emptiness. Not for a woman so much as for a child—I would like to have had a son. That’s the emptiness.”

“What do you do?”

His answers were coming slowly. “I try to take desires and memories of companionship—destructive ones—and let them run their course. Wait it out. Don’t panic. That’s when the emptiness is intense.”

“And that’s it?”

“That’s the beginning. Then I turn the pain of absence into an offering to God. Sometimes that’s all I have to offer.”