Bloody Mary (31 page)

Authors: Carolly Erickson

It was the intention of the Protector and Archbishop Cranmer to ride the crest of this tide of dissatisfaction and to harness its discontent through the formulation of a new creed. The first steps were taken soon after Edward’s accession, when all the legislation regulating the Henri-cian church was repealed. Restrictions on the printing and reading of the Bible were lifted, and Cranmer began work on an English communion service to replace the mass, which would come into use early in 1548. It was essential that there be no organized Catholic opposition to this program, and it was here that Mary presented an embarrassment. As the official faith of England moved further away from Rome, Mary could be counted on to remain loyal to the old faith. While Henry lived her Catholicism had been tolerated, once she renounced allegiance to the pope. But when the new teachings and services came into existence her adherence to the mass, the festivals and the doctrines of Rome would seem an insult to the religious establishment, and would encourage the vast numbers of Catholics who had never been reconciled to any change in the faith to resist.

And as always, the issue of religion had its diplomatic dimension. Any move toward Lutheranism in England was bound to bring on the disapproval of the emperor, who in the spring of 1547 was stronger than ever after achieving a significant victory over the German Protestants at Miihlberg. The French, always intent on driving a wedge between imperial and English interests, were already at work raising fears of invasion. Within six weeks of Henry’s death the French king was telling the English ambassador in Paris that the emperor planned to make war on the English, on the pretext that Mary and not Edward was the true heir.

5

Even if he did not invade England Charles was certain to support Mary’s continued fidelity to her Catholic confession, and to back any rebellion against the Protestant government that might take shape as the religious alterations advanced.

What made matters worst for the Council was that Mary was now heir apparent. It was common knowledge that, should Edward die without an heir, Mary was designated his successor under the terms of the late king’s will. Certain knowledge that a Catholic would succeed should harm come to the king was bound to give rise to assassination plots and political conspiracies both in England and on the continent, where for years the pope had been urging Reginald Pole and others to find the means to de

stroy Protestanrism and restore the true faith. In the light of these dangers the most influential of Edward’s councilors took varying attitudes toward Mary. The Protector, fearing above all the international complications she might trigger, thought that if she could be kept in the background, away from court and out of the view of the public and

the

diplomats, the twin problems of her divergent faith and her popular influence would be minimized. Obsessed as he was with waging war against the Scots, he tended to treat Mary as a minor irritant to be dealt with as the need arose. There had never been any personal enmity between Mary and Somerset up to now, and Mary was known to be on good terms with his wife Anne, whom she called her gossip and “her good Nan.” Anne Seymour had been a maid of honor in Katherine of Aragon’s household; apparently this endeared her to Mary, who now wrote her on behalf of several elderly former servants of Katherine. They were infirm and without employment, Mary explained, and she wondered whether Nan would ask her husband to secure them pensions.

The three Council members who stood next to the Protector in influence—Paget, Dudley and Thomas Seymour—had somewhat different views. Paget, a supple man of impermanent commitments, echoed Somerset’s recommendation at the Council table but privately worried that Mary posed a greater threat than the Protector realized. Paget favored conciliatory talk up to the last possible moment: then expedient action. Mary should be allowed to live and worship as she liked until it gave rise to problems; then she would have to be given an ultimatum and, if necessary, dealt with by force. Dudley, an able, unprincipled soldier who was now the third man in the Council, saw Mary as only one of many components in a rapidly shifting political game. He was prepared to force her to renounce her faith if that became necessary, but his primary concern was taking over leadership of the Council himself, and supplanting Somerset. The last of the leading figures, Thomas Seymour, had the most original suggestion for bringing Mary under the control of the Council: he offered to matry her.

Thomas Seymour, whose unsavory charm and ambition were as obvious as his transparendy gauche tactics, had like Dudley made up his mind to rise to the top position in the Council. He saw two ways to do this—by winning the heart of his nephew the king and by making a royal marriage. In the admiral’s pay was one Thomas Fowler, a gentleman of Edward’s privy chamber who brought the king presents from his uncle and spoke on his behalf whenever he and Edward were alone. On one occasion Fowler brought up the issue of Seymour’s marriage, and asked the king whom he would recommend as a suitable wife. Edward’s first suggestion, Anne of Cleves, would doubtless have chilled the admiral’s blood,

but on second thought Edward told Fowler “I would he married my sister Mary, to change her opinions.”

Greatly heartened, Seymour next went to gain the approval of his brother the Protector. But far from giving his brother permission to marry the heir to the throne Somerset “reproved him, saying that neither of them was born to be king, nor to marry a king’s daughter.” They must “thank God and be satisfied” with their present honors, and not presume higher. Besides, the Protector added, Mary would never consent. (In fact it was rumored that before approaching either his brother or the king the admiral had proposed to both Mary and Elizabeth, who flatly turned him down.) The admiral, offended, answered that all he sought was approval for the match, and that he would overcome the obstacle of gaining Mary’s consent in his own fashion. But this led to another sharp burst of outrage from Somerset, and the conversation ended with bad feeling on both sides that never fully healed. In a few months Thomas Seymour secretly married his old love Catherine Parr, while she was still in mourning for Henry.

In keeping with the Protector’s policy Mary was kept away from Edward and the court from the start of Edward’s reign. She moved back and forth from Havering, Edward’s old residence in Essex, to Wanstead House, New Hall and Framlingham Castle in Norfolk, near the estates which now provided her modest income. She saw little of Catherine Parr either before or after her marriage to Thomas Seymour, and was so far from court that the imperial ambassador, Francois Van der Delft (Chapuys had left England in 1545), could not see her easily. He learned indirectly that she was being held in “very little account,” and was upset over some vague slight from the Council; she was also put out, he heard, that the Protector did not write or visit her with the news of Henry’s death for several days after it occurred.

6

When Van der Delft was finally able to speak to Mary at some length in July of 1547, he found her to be in semi-seclusion out of respect to her father. Henry was still “very rife in her remembrance,” she wrote at about this time, and to Van der Delft she explained that in deference to his memory she had not dined in public since his death. She made an exception for the ambassador, and insisted that he dine with her. Mary did not hesitate to put her trust in Chapuys’ successor. “She seemed to have entire confidence in me,” he wrote afterward, and though their conversation was relatively casual he felt and appreciated Mary’s customary openness and lack of formality. They spoke of her income, which Van der Delft thought was far too low considering her standing in the succession; of her father’s will, whose authenticity she doubted, but could not prove one way or the other; of the amount of her dowry, about which she knew nothing; and finally of the marriage of Catherine Parr and

Thomas Seymour. Mary asked Van der Delft what he thought of it, and after indicating his general approval he alluded to the rumor that the admiral had proposed to Mary first. She laughed, saying that “she had never spoken to him in her life, and had only seen him once,” and made light of the suggestion.

7

The admiral was in fact fast overreaching himself. He had offended the Protector and Council by marrying Catherine without their approval. He was putting pressure on Edward to advance him beyond his brother, and he was known to be searching the lawbooks for a precedent in which, with the king a minor, one uncle governed the kingdom and the other the person of the king. After a year or so his attempts to win Edward over were at least partially successful, but his swaggering efforts to become the first man in the Council made him universally despised. He tried to ride on his wife’s former rank as queen dowager, but fierce confrontations between Catherine and the tenacious duchess of Somerset were the only result. He intrigued to marry Edward to his cousin Jane Grey, a daughter of Edward Grey who had been brought up in the admiral’s household, contrary to the Protector’s cherished plan to marry the young king to Mary of Scotland. And he abused his office with a thorough and imaginative criminality remarkable even in an age of accomplished corruption.

Among his earliest commissions as admiral was the task of capturing one “Thomessin,” a pirate operating out of the Scilly Isles and preying on the ships of all nations. Seymour returned from his mission without Thomessin, but having discovered a profitable new avenue of self-enrichment. He agreed with the pirate and his confederates that he would not interfere with their trade provided they gave him a share of everything they seized. He made similar agreements with the privateers of the southern coast, and in effect became a pirate himself. Taking advantage of the Protector’s absence in Scotland he tried to organize a force of sworn adherents and boasted that he could call ten thousand men to his aid if need be, and could arm them from a large private cache of weapons and ammunition. Through a confederate he arranged to embezzle funds from the Bristol mint to finance his illegal private army, and by the fall of 1548 he had become the most dangerous man in the kingdom.

It was then that his schemes began to backfire. Early in September Catherine Parr died giving birth to a daughter, and Seymour’s immediate renewal of his proposal to Elizabeth—with whom he had enjoyed a long and scandalous flirtation—made his unashamed ambition more obvious than ever. Determined somehow to use the king for his own ends he obtained first a stamp of Edward’s signature and then keys to many of the royal apartments, and late one night he broke into the king’s bedchamber, his retinue at his heels, and shot Edward’s little lapdog when it tried to

bite him. The sheer folly of this adventure seemed to prove that in his desperation the admiral had lost his judgment. He was arrested and, as his misdemeanors came to light, charged with high treason. In March of 1549 he was executed on Tower Hill, the first victim of the self-devouring coterie of councilors that was daily drawing more and more power to itself.

The poor at enclosing do grudge,

The poor at enclosing do grudge,

because of abuses that fall,

Lest some men should have but too much,

and some again nothing at all.

In the spring and summer of 1549 the commons of England rose in massive protest against the government. There was violence in Hertfordshire, Essex, Norfolk, Gloucestershire and a half dozen other places; in Oxfordshire an incipient revolt broke out. In Cornwall pent-up grievances exploded early in June when by government order the new English communion service was read on Whitsunday in place of the Latin mass. The following day the parishioners of one Cornish village forced their priest to promise to bring back the mass, and before long the new service was thrown out in many Cornish towns and the mass restored. Meanwhile parts of Devon had risen and a large crowd was massing for an assault on Exeter, the largest town in the West Country.

The rebels besieged the town while the force sent by the Council to subdue them stood by and did nothing. The commander Lord Russell, a seasoned veteran of Henry’s campaigns, saw that his fighting men were too few, and waited for reinforcements. As he waited the rebel army grew stronger, and the siege of Exeter gave added urgency to the insurgents’ demands. They complained of food shortages and high prices, but their principal demands concerned the religious changes. They wanted to keep the mass and to have the old statues and pictures of Jesus, the virgin Mary and the saints restored. The litanies, offices and familiar sacraments should be brought back, they insisted, along with the blessed bread and holy water, and at Eastertime, the palms and ashes. Two of their demands show how eager they were to return to the days before re

form doctrines had been mooted in England: they wanted two abbeys rebuilt in every country, and they wanted Cardinal Pole to be brought back from his exile and placed in King Edward’s Council.

In August the West Country rebels were finally defeated, but not before the commons of Norfolk had risen in a widespread and potentially dangerous protest that had something of the millennial character of medieval popular revolts. Led by the wealthy tanner Robert Ket, the Norfolk rebels tore through the grazing lands around Norwich, pulling up fences, breaking hedges and obliterating every boundary marker that symbolized the private seizure of what had been common land. After a time they gathered in a huge camp at Mousehold Heath, two miles from Norwich, and as their numbers grew they set up a loosely organized community whose leaders called themselves “commissioners” of the “King’s Great Camp at Mousehold.” There were at least ten thousand of them—some said nearer twenty—and it took an alarmingly large royal force to subdue them. Dudley was at the head of that force. He took Norwich on August 24, and three days later faced Ket and his men at Dussindale. Leaving much of the fighting to his German mercenaries, Dudley’s men carried out a merciless slaughter. When the battle ended, more than three thousand rebels lay dead on the field. The survivors straggled home, their leaders seized as prisoners and executed. Ket was hanged on Norwich Castle, and nine others on the “Oak of Reformation” on Mousehold Heath.

The revolts of 1549 seemed to confirm the worst fears of the Council—that beneath the uneasy acquiescence of the people lay deep dissatisfactions with religion and government which an inflammatory incident or a popular leader could trigger into violence. In mid-July, when the revolts in the west and north were in full cry, spontaneous uprisings in the counties around London made Council members frightened for their own safety. Mobs of angry tenants moved in disorderly fashion toward the capital, coming so dangerously close that at one point they broke the fences of one of the king’s parks at Elton near Greenwich. It was said they planned to besiege London until all rebel prisoners were returned to them alive, and rumors of every sort—including revived fears of reprisals against foreigners—spread throughout southern England in the anxious weeks before the rebellions ended.

1

Behind the rebels’ immediate grievances lay the pent-up frustrations of decades of severe hard times in the countryside. The process known as enclosure, in which large areas of farmland and the meadows and pastures that for centuries had been held in common were fenced in by landlords to make grazing land for sheep, swept away many small farms and caused entire villages to shrink or to disappear altogether. Social critics of the time bemoaned the hundreds of deserted villages to be found throughout

England, their ruined churches and houses a poignant witness to the once flourishing rural life that had gone forever. Sometimes the very ruins themselves were obliterated. “I know towns,” wrote one observer, “so wholly decayed, that there is neither stick nor stone standing.”

The displaced farmers wandered the roads searching for another few acres to make a fresh start. Some made it to the capital, and survived there; many did not, and became a marginal vagabond population, distrusted by all who saw them and treated with brutality or indifference by the government that feared them. Those who hung on to their farms amid the upheaval in rural life found themselves faced with enormous increases in rents and other fees; landlords were accused of inhuman exploitation and every sort of rapacity. Edward VI’s Primer contained a “Prayer for Landlords” asking God that “they, remembering themselves to be thy tenants, may not rack, and stretch out the rents of their houses and lands.” Between the enclosing of the fields and the raising of rents fewer acres were being farmed, so that as the numbers of the landless and the unemployed grew, there was less and less food to go around. A contemporary believed that for every plow idled six men lost their livings, and seven more their sustenance. And this at a time when the population as a whole was increasing faster than at any time in the last two hundred years.

In the face of this turmoil the frightened members of the ruling Council took refuge in shrill reiterations of the importance of obedience and maintenance of the social order. To be discontented with one’s lot was a sin against the divine order, they insisted. For God has ordained that “some are in high degree, some in low, some kings and princes, some inferiors and subjects, some rich and some poor,” and to chafe against these preordained categories was to loose the evils of “abuse, carnal liberty, enormity, sin and babylonical confusion.”

2

Take away the agents of the divinely appointed social hierarchy—rulers, magistrates, judges and the natural leaders, the aristocracy—and the result would be that “no man shall ride or go by the highway unrobbed, no man shall sleep in his own house or bed unkilled, no man shall keep his wife, children and possessions in quietness.”

Beyond making pronouncements such as these the government did little to alleviate the crisis. The one positive policy was the ill-advised expedient of debasing the coinage. Henry VIII had periodically ordered more base metal mixed with the gold and silver of his coins, and in other ways manipulated the currency for profit. He made perhaps half a million pounds in this way to add to his treasury, but by the 1540s his debts were so huge that the profit from the mint could not begin to cancel them. The 1544 campaign in France and the border warfare with the Scots in the final years of his reign cost him more than two million

pounds, and he had to borrow heavily from the merchant bankers of Antwerp to keep barely ahead of his creditors at home. When Henry died he left his debts to his son, and in Edward’s name the Protector ordered still further debasement. By 1549 most coins had dropped to slightly more than half of what they had been worth when the decade began, with the result that food costs doubled or tripled.

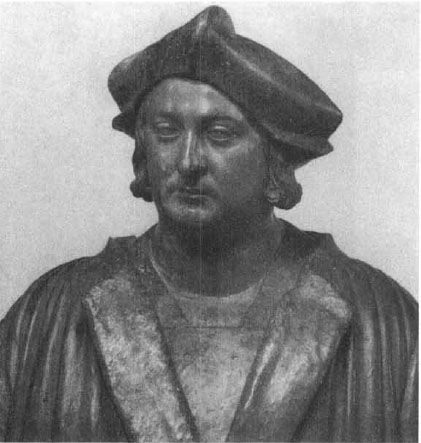

3a. Pietro Torrigiano’s bust of the young Henry VIII.

METROPOLITAN MUSEUM OF ART.

3b. Katherine of Aragon in middle age, ca. 1530. Artist unknown.

NATIONAL PORTRAIT GALLERY, LONDON.

4. Anne Boleyn. Artist unknown.

NATIONAL PORTRAIT GALLERY, LONDON.

5. Henry VIII, ca. 1520. Artist unknown.

NATIONAL PORTRAIT GALLERY, LONDON.

6. Catherine Parr, ca. 1550. Artist unknown.

NATIONAL PORTRAIT GALLERY, LONDON.