Bloody Crimes (42 page)

“Colonel, do you hear that firing?” Jim asked.

Johnston sprang up and commanded, “Run and wake the president.”

Jones also woke Burton Harrison: “I was awakened by the coachman, Jim Jones, running to me about day-break with the announcement that the enemy was at hand!”

As Harrison sprang to his feet, he heard musket fire on the north side of the creek. He drew his pistol just in time to confront several men from the Fourth Michigan charging up the road from the south. Harrison raised his weapon and took aim.

“As soon as one of them came within range,” he remembered, “I covered him with my revolver and was about to fire, but lowered the weapon when I perceived the attacking column was so strong as to make resistance useless, and reflected that, by killing the man, I should certainly not be helping ourselves, and might only provoke a general firing upon the members of our party in sight. We were taken by surprise, and not one of us exchanged a shot with the enemy.” William Preston Johnston didn’t hear any more gunfire and began to pull on his boots. He walked out to the campfire to ask the cook if Jim had been mistaken.

“At this moment,” Johnston reported, “I saw eight or ten men charging down the road towards me. I thought they were guerillas, trying to stampede the stock. I ran for my saddle, where I had slept, and began unfastening the holster to get out my revolver, but they were too quick for me. Three men rode up and demanded my pistol, which…I gave to the leader…dressed in Confederate gray clothes…One of my captors ordered me to the camp fire and stood guard over me. I soon became aware that they were federals.”

Lubbock was up too. “We sprang immediately to our feet.” Lubbock pulled his boots on, stood up, and secured his horse, which had

been saddled all night and was tied near where the governor had laid down his head. It was too late. “By this time the Federal troopers were on us. We were scarce called upon to surrender before they pounced upon us like freebooters.”

Lubbock put up a fight, resisting an attempt by two of the cavalrymen to rob him. Reagan saw it all:

When this firing occurred the troops in our front galloped upon us. The major of the regiment reached the place where I and the members of the President’s staff were camped, about one hundred yards from where the President and his family had their tents. When he approached me I was watching a struggle between two federal soldiers and Governor Lubbock. They were trying to get his horse and saddle bags away from him and he was holding on to them and refusing to give them up; they threatened to shoot him if he did not, and he replied…that they might shoot and be damned, but that they should not rob him while he was alive and looking on.

A Union officer spotted Reagan and spurred his horse toward the only member of the Confederate cabinet who had volunteered to remain with the president. The postmaster-general readied his pistol.

“I had my revolver cocked in my hand, waiting to see if the shooting was to begin,” he remembered. “Just at this juncture the major rode up, the men contending with Lubbock had disappeared, and the major asked if I had any arms. I drew my revolver from under the skirt of my coat and said to him, ‘I have this.’ He observed that he supposed I had better give it to him. I knew that there were too many for us and surrendered my pistol.”

Pritchard rode up to Harrison and demanded to know the source of the shooting. “Pointing across the creek, [he] said, ‘What does that mean? Have you any men with you?’ Supposing the firing was done by our teamsters, I replied, ‘Of course we have—don’t you hear the

firing?’ He seemed to be nettled at the reply, gave the order, ‘Charge,’ and boldly led the way himself across the creek, nearly every man in his command following.”

S

till inside Varina’s tent, Davis heard the gunfire and the horses in the camp and assumed these were the same Confederate stragglers or deserters who had been planning to rob Mrs. Davis’s wagon train for several days.

“Those men have attacked us at last,” he warned his wife. “I will go out and see if I cannot stop the firing; surely I still have some authority with the Confederates.”

He opened the tent flap, saw the bluecoats, and turned to Varina: “The Federal cavalry are upon us.”

Jefferson Davis had not faced a cavalry charge for two decades. The last time he was in battle, he was in command of his beloved regiment of Mississippi Rifles at the Battle of Buena Vista in the Mexican War. There he encountered one of the most frightening sights a man could see on a nineteenth-century battlefield—massed lancers preparing to charge. The lance was not a toy, and at close quarters it could be more deadly than a pistol or saber. Napoleon’s lancers had been feared throughout Europe, and Mexican lancers had slaughtered American soldiers with ease in California and Mexico. Indeed, Colonel Samuel Colt had perfected his dragoon revolver for the express purpose of shooting down charging Mexican lancers. At Buena Vista, Davis’s regiment was outnumbered and at risk of being overrun in moments. Davis ordered his men form an inverted formation of the letter

V,

allow the Mexicans to charge into the open

V

and, at the last moment, unleash a devastating rifle volley into them. It worked, and the Mississippi Rifles broke the charge. That victory made Davis a hero, and, in a circuitous route, his military fame two decades earlier had led him to this camp in the pinewoods of Georgia. But this morning he had too little advance warning and not enough men to

resist the charge of the Fourth Michigan.

Davis had not undressed this night, so he was still wearing his gray frock coat, trousers, riding boots, and spurs. He was ready to leave now, but he was unarmed. His pistols and saddled horse were within sight of the tent. If he could just get to that horse, he could leap into the saddle, draw a revolver, and gallop for the woods, ducking low to avoid any carbine or pistol fire aimed in his direction. He knew he was still a superb equestrian and was sure he could outrace any Yankee cavalryman half his age. Seconds, not minutes, counted now, and if he hoped to escape he had to run for the horse.

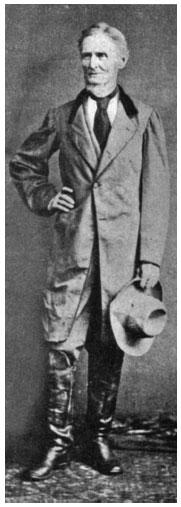

ON THE MORNING OF HIS CAPTURE, JEFFERSON DAVIS WORE A SUIT OF CONFEDERATE GRAY AND NOT ONE OF VARINA’S HOOPSKIRTS.

John Taylor Wood got free of the cavalry and tried to help Davis: “I went over to the president’s tent, and saw Mrs. Davis. [I] told her that the enemy did not know that he was present and during the confusion he might escape into the swamp.”

Before Jefferson left, Varina asked him to wear an unadorned raglan overcoat, also known as a “waterproof.” Varina hoped the raglan might camouflage his fine suit of clothes, which resembled a Confederate officer’s uniform. “Knowing he would be recognized,” Varina explained, “I plead with him to let me throw over him a large water

proof which had often served him in sickness during the summer as a dressing gown, and which I hoped might so cover his person that in the grey of the morning he would not be recognized. As he strode off I threw over his head a little black shawl which was round my own shoulders, seeing that he could not find his hat and after he started sent the colored woman after him with a bucket for water, hoping he would pass unobserved.”

Jefferson Davis described what happened that morning:

As I started, my wife thoughtfully threw over my head and shoulders a shawl. I had gone perhaps between fifteen or twenty yards when a trooper galloped up and ordered me to halt and surrender, to which I gave a defiant answer, and, dropping the shawl and the raglan from my shoulders, advanced toward him; he leveled his carbine at me, but I expected, if he fired, he would miss me, and my intention was in that event to put my hand under his foot, tumble him off on the other side, spring into the saddle, and attempt to escape. My wife, who had been watching me, when she saw the soldier aim his carbine at me, ran forward and threw her arms around me. Success depended on instantaneous action, and recognizing that the opportunity had been lost, I turned back, and, the morning being damp and chilly, passed on to a fire beyond the tent…

E

ven before the gun battle ceased, some of the cavalrymen started tearing apart the camp in a mad scramble. They searched the baggage, threw open Varina’s trunks, and tossed the children’s clothes into the air. “The business of plundering commenced immediately after the capture,” observed Harrison. The frenzy on the part of the cavalry suggested that the search was not random. The Yankees were looking for something.

Lubbock said that “in a short time they were in possession of

very nearly everything of value that was in the camp. I resisted being robbed, and lost nothing then except some gold coin that was in my holsters. I demanded to see an officer, and called attention to the firing, saying that they were killing their own men across the branch, and that we had no armed men with us…While a stop was being put to this I went over to Mr. Davis, who was seated on a log, under guard.”

Johnston was not as lucky resisting the plunderers. Several cavalrymen got his horse and his saddle, with the accoutrements and pistols, which his father, General Albert Sidney Johnston, had used at the Battle of Shiloh on the day he was killed in action. Understandably, the son prized his father’s personal effects.

Harrison did not want his captors to lay their vulgar hands on the letters from Constance Cary he carried with him all the way from Richmond: “I emptied the contents of my haversack into a fire where some of the enemy were cooking breakfast, and they saw the papers burn. They were chiefly love-letters, with a photograph of my sweetheart.”

A

s the skirmish between the Union regiments died down, Colonel Johnston’s guard left him unattended and he walked fifty yards to Varina Davis’s tent, where he found the president outside. “This is a bad business, sir,” Davis said, “I would have heaved the scoundrel off his horse as he came up, but she caught me around the arms.”

“I understood what he meant,” Johnston said, “how he had proposed to dismount the trooper and get his horse, for he had taught me the trick.” It was an old Indian move that Davis had learned years before when he served out west in the U.S. Army.

Once Davis had been apprehended, John Taylor Wood decided to escape. “Seeing that there was no chance for the President I determined to make the effort.” Lubbock and Reagan approved his plan. Wood strolled around the camp, examining the faces of the Union

cavalrymen, until “at last I selected one that I thought would answer my purpose.” He asked the soldier to go to the swamp with him, where Wood offered him forty dollars. The Yankee grabbed the money and let him go.

Johnston warned another Union officer that they were firing on their own men: “Feeling that the cause was lost, and not wishing useless bloodshed, I said to him: ‘Captain, your men are fighting each other over yonder.’ He answered very positively: ‘You have an armed escort.’ I replied, ‘You have our whole camp; I know your men are fighting each other. We have nobody on that side of the slough.’ He then rode off.”

Soon Pritchard and his officers discovered that this was true. There were no Confederate soldiers behind the camp. His men were fighting the First Wisconsin Cavalry, and they were killing each other. Greed for gold and glory may have contributed to the deadly and embarrassing disaster. The troopers of the Fourth Michigan and the First Wisconsin cavalries knew nothing about President Johnson’s proclamation of May 2, offering a $100,000 reward for the capture of Jefferson Davis. They were not after that reward money, although once they learned of it, a few days after the Davis capture, they were eager to claim it. No, they wanted a bigger prize—Confederate gold. Every Union soldier had heard the rumors that the “rebel chief” was fleeing with millions of dollars in gold coins in his possession.

The Northern newspapers had reported it, Edwin M. Stanton and a number of Union generals had telegraphed about it, and, no doubt, every last man of the Fourth Michigan and First Wisconsin had heard about it. The lure of the so-called Confederate “treasure train” was irresistible. General James Wilson’s broadside proclamation of May 9, which General Palmer had printed and then distributed as handbills in Georgia, intoxicated Union soldiers with dreams of untold riches.

Eliza Andrews had seen the reward posters:

The hardest to bear of all the humiliations yet put upon us, is the sight of Andy Johnson’s proclamation offering rewards for the arrest of Jefferson Davis, Clement C. Clay, and Beverly Tucker, under pretense that they were implicated in the assassination of Abraham Lincoln. It is printed in huge letters on handbills and posted in every public place in town—a flaming insult to every man, woman, and child in the village, as if [the Yankees] believed there was a traitor among us so base as to betray the victims of their malice, even if they knew where they were…if they had posted one of their lying accusations on our street gate, I would tear it down with my own hands, even if they sent me to jail for it.

Wilson had promised this: Whoever captured Davis could claim the millions of dollars in gold he was carrying as their reward. But what these man hunters did not know was that Davis was not the one transporting it.