Bloodlands: Europe Between Hitler and Stalin (62 page)

Read Bloodlands: Europe Between Hitler and Stalin Online

Authors: Timothy Snyder

Tags: #History, #General, #Biography & Autobiography, #European History, #Europe; Eastern - History - 1918-1945, #Political, #Holocaust; Jewish (1939-1945), #World War; 1939-1945 - Atrocities, #Europe, #Eastern, #Soviet Union - History - 1917-1936, #Germany, #Soviet Union, #Genocide - Europe; Eastern - History - 20th century, #Russia & the Former Soviet Union, #Holocaust, #Massacres, #Genocide, #Military, #Europe; Eastern, #World War II, #Hitler; Adolf, #Presidents & Heads of State, #Massacres - Europe; Eastern - History - 20th century, #World War; 1939-1945, #20th Century, #Germany - History - 1933-1945, #Stalin; Joseph

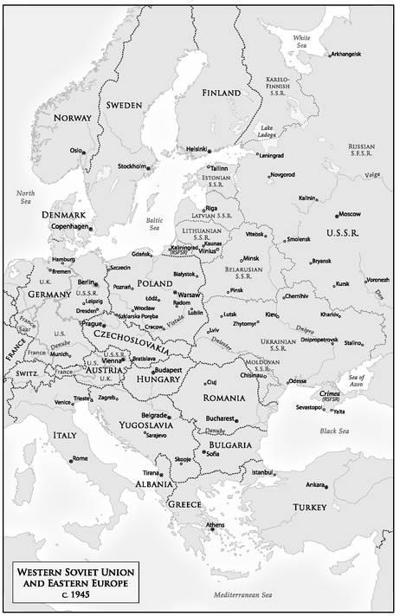

Under Stalin, the Soviet Union had evolved, slowly and haltingly, from a revolutionary Marxist state into a large, multinational empire with a Marxist covering ideology and traditional security concerns about borders and minorities. Because Stalin inherited, maintained, and mastered the security apparatus of the revolutionary years, these anxieties could be released in bursts of national killing in 1937-1938 and 1940, and in bouts of national deportation that began in 1930 and continued throughout Stalin’s lifetime. The deportations of the war continued a certain evolution in Soviet deportation policy: away from the traditional resettlements of individuals thought to represent enemy classes, and toward an ethnic cleansing that matched populations to borders.

In the prewar period, the deportations to the Gulag were always meant to serve two purposes: the growth of the Soviet economy and the correction of the Soviet population. In the 1930s, as the Soviets began to deport large numbers of people on ethnic grounds, the goal was to move national minorities away from sensitive border regions toward the interior. These national deportations could hardly be seen as a specific punishment of individuals, but they were still premised on the assumption that those deported could be better assimilated into Soviet society when they were separated from their homes and homelands. The national actions of the Great Terror killed a quarter of a million people in 1937 and 1938, but also dispatched hundreds of thousands of people to Siberia and Kazakhstan, where they were expected to work for the state and reform themselves. Even the deportations of 1940-1941, from annexed Polish, Baltic, and Romanian territories, can be seen in Soviet terms as a class war. Men of elite families were killed at Katyn and other sites, and their wives, children, and parents left to the mercy of the Kazakh steppe. There they would integrate with Soviet society, or they would die.

During the war, Stalin undertook punitive actions that targeted national minorities for their association with Nazi Germany. Some nine hundred thousand Soviet Germans and about eighty-nine thousand Finns were deported in 1941 and 1942. As the Red Army moved forward after the victory at Stalingrad in early 1943, Stalin’s security chief Lavrenty Beria recommended the deportation of whole peoples accused of collaborating with the Germans. For the most part, these were the Muslim nations of the Caucasus and Crimea.

40

As Soviet troops retook the Caucasus, Stalin and Beria put the machine into action. On a single day, 19 November 1943, the Soviets deported the entire Karachai population, some 69,267 people, to Soviet Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan. Over the course of two days, 28-29 December 1943, the Soviets dispatched 91,919 Kalmyks to Siberia. Beria went to Grozny personally to supervise the deportations of the Chechen and Ingush peoples on 20 February 1944. Leading about 120,000 special forces, he rounded up and expelled 478,479 people in just over a week. He had at his disposal American Studebaker trucks, supplied during the war. Because no Chechens or Ingush were to be left behind, people who could not be moved were shot. Villages were burned to the ground everywhere; in some places, barns full of people were burned as well. Over the course of two days, 8-9 March 1944, the Soviets removed the Balkar population, 37,107 people, to Kazakhstan. In April 1944, right after the Red Army reached the Crimea, Beria proposed and Stalin agreed that the entire Crimean Tatar population be resettled. Over the course of three days, 18-20 March 1944, 180,014 people were deported, most of them to Uzbekistan. Later in 1944, Beria had the Meshketian Turks, some 91,095 people, deported from Soviet Georgia.

41

Against this backdrop of essentially continuous national purges, Stalin’s decision to cleanse the Soviet-Polish border seems like an unsurprising development of a general policy. From a Soviet perspective, Ukrainian, Baltic, or Polish partisans were simply more bandits causing trouble along the periphery, to be dealt with by overwhelming force and deportations. There was, however, an important difference. All of the kulaks and members of national minorities deported in the 1930s found themselves far from home, but still within the USSR. The same was true of the Crimean and Caucasian and Baltic populations deported during and shortly after the war. Yet in September 1944, Stalin opted to move Poles (and Polish Jews), Ukrainians, and Belarusians back and forth across a

state

border in order to create ethnic homogeneity. The same logic was applied, on a far greater scale, to the Germans in Poland.

Working in parallel, and sometimes together, the Soviet and communist Polish regimes achieved a curious feat between 1944 and 1947: they removed the ethnic minorities, on both sides of the Soviet-Polish border, that had made the border regions mixed; and at the very same time, they removed the ethnic nationalists who had fought the hardest for precisely that kind of purity. Communists had taken up the program of their enemies. Soviet rule had become ethnic cleansing—cleansed of the ethnic cleansers.

The territory of postwar Poland was the geographical center of Stalin’s campaign of postwar ethnic cleansing. In that campaign, more Germans lost their homes than any other group. Some 7.6 million Germans had left Poland by the end of 1947, and another three million or so were deported from democratic Czechoslovakia. About nine hundred thousand Volga Germans were deported within the Soviet Union during the war. The number of Germans who lost their homes during and after the war exceeded twelve million.

Enormous as this figure was, it did not constitute a majority of the forced displacements during and after the war. Two million or so non-Germans were deported by Soviet (or communist Polish) authorities in the same postwar period. Another eight million people, most of them forced laborers taken by the Germans, were returned to the Soviet Union at the same time. (Since many if not most of them would have preferred not to return, they could be counted twice.) In the Soviet Union and Poland, more than twelve million Ukrainians, Poles, Belarusians, and others fled or were moved during the war or in its aftermath. This does not include the ten million or so people who were deliberately killed by the Germans, most of whom were displaced in one way or another before they were murdered.

42

The flight and deportation of the Germans, though not a policy of deliberate mass killing, constituted the major incident of postwar ethnic cleansing. In all of the civil conflict, flight, deportation, and resettlement provoked or caused by the return of the Red Army between 1943 and 1947, some 700,000 Germans died, as did at least 150,000 Poles and perhaps 250,000 Ukrainians. At a minimum, another 300,000 Soviet citizens died during or shortly after the Soviet deportations from the Caucasus, Crimea, Moldova, and the Baltic States. If the struggles of Lithuanian, Latvian, and Estonian nationalists against the reimposition of Soviet power are regarded as resistance to deportations, which in some measure they were, another hundred thousand or so people would have to be added to the total dead associated with ethnic cleansing.

43

In relative terms, the percentage of Germans moved as a part of the total population of Germans was much inferior to that of the Caucasian and Crimean peoples, who were deported down to the last person. The percentage of Germans who moved or were moved at the end of the war was greater than that of Poles, Belarusians, Ukrainians, and Balts. But if the population movements caused by the Germans during the war are added to those caused by the Soviet occupation at war’s end, this difference disappears. Over the period 1939-1947, Poles, Ukrainians, Belarusians, and Balts were about as likely (some a bit more, some a bit less) to have been forcibly moved as Germans. Whereas all of the other peoples in question faced hostile German and Soviet policies, the Germans (with some exceptions) experienced oppression only from the Soviet side.

In the postwar period, Germans were about as likely to lose their lives as Poles, the other group that was mainly sent west to a national homeland. Germans and Poles were much less likely to die than Ukrainians, Romanians, Balts, and the Caucasian and Crimean peoples. Fewer than one in ten Germans and Poles died during or as a direct result of flight, exile, or deportation; among Balts and Soviet citizens, the rate was more like one in five. As a general rule, the further east the deportation, and the more directly Soviet power was involved, the more deadly the outcome. This is evident in the case of the Germans themselves: the tremendous majority of Germans who fled Poland and Czechoslovakia survived, whereas a large proportion of those transported east within or to the Soviet Union died.

It was better to be sent west than east, and better to be sent to an awaiting homeland than to a distant and alien Soviet republic. It was also better to land in developed (even if bombed and war-torn) Germany than in Soviet wastelands that deportees were supposed to develop themselves. It was better to be received by British and American authorities in occupation zones than by the local NKVD in Kazakhstan or Siberia.

Rather quickly, within about two years after the end of the war, Stalin had made his new Poland and his new frontiers, and moved peoples to match them. By 1947, it might have seemed that the war was finally over, and that the Soviet Union had well and truly won a military victory over the Germans and their allies and a political victory over opponents of communism in eastern Europe.

Poles, always a troublesome group, had been dispatched from the Soviet Union to a new communist Poland, bound now to the Soviet Union as the anchor of a new communist empire. Poland, it might have seemed, had been subdued: twice invaded, twice subject to deportations and killings, altered in its borders and demography, ruled by a party dependent on Moscow. Germany had been utterly defeated and humiliated. Its territories as of 1938 were divided into multiple occupation zones, and would find their way into five different sovereign states: the Federal Republic of Germany (West Germany), the German Democratic Republic (East Germany), Austria, Poland, and the USSR (at Kaliningrad). Japan had been utterly defeated by the Americans, its cities firebombed or, at the very end, destroyed by nuclear weapons. It was no longer a power in continental Asia. Stalin’s traditional threats had been removed. The prewar nightmare of a Japanese-Polish-German encirclement was passé.

More Soviet citizens had died in the Second World War than any people in any war in recorded history. At home, Soviet ideologists had taken advantage of the suffering to justify Stalinist rule: as the necessary price of victory in what was called “the Great Patriotic War.” The patria in question was Russia as well as the Soviet Union; Stalin himself famously raised a toast to “the great Russian nation” just after the war’s end, in May 1945. Russians, he maintained, had won the war. To be sure, about half the population of the Soviet Union was Russian, and so in a numerical sense Russians had played a greater part in the victory than any other people. Yet Stalin’s idea contained a purposeful confusion: the war on Soviet territory was fought and won chiefly in Soviet Belarus and in Soviet Ukraine, rather than in Soviet Russia. More Jewish, Belarusian, and Ukrainian civilians had been killed than Russians. Because the Red Army took such horrible losses, its ranks were filled by local Belarusian and Ukrainian conscripts at both the beginning and the end of the war. The deported Caucasian and Crimean peoples, for that matter, had seen a higher percentage of their young people die in the Red Army than had the Russians. Jewish soldiers had been more likely to be decorated for valor than Russian soldiers.