Blood Work (12 page)

Authors: Holly Tucker

Perrault, Gayant, and Auzout continued their work between January 22 and March 21, 1667. The dogs were dying less oftenâbut the men remained doubtful. How could they be sure that any blood was actually being transfused? In order to confirm the transfer of blood, their last experiment took place on a scale. Weights were stacked in a pan along with the lighter dog in order to balance it with the heavier dog. Once everything was in place, they began the two-way transfusion. The scale rose on one side and lowered on the other. Then suddenly it rebalanced itself and

began a fluid dance of up-and-down movements. All told, one dog had received five and a half ounces of blood; the second received just over six ouncesâabout two-thirds of a cup each. Both dogs died shortly afterward.

For Perrault his failed experiments put English claims about transfusion to rest. The physician argued repeatedly that his trials had more than amply demonstrated the “impossibility that Nature finds in accommodating herself to an alien blood.” Blood prepared in the body of one animal was simply not able to nourish the flesh of another. His own experiments, Perrault pointed out, had shown that even the transfer of blood between a single species was fatal. This was precisely the reason for the presence of the umbilical cord and placenta in mammals: “For although the blood of the mother has a great resemblance to that of the fetus, nevertheless it does not at all pass directly from the vessels of the mother into those of the fetus, because it is in reality a foreign blood, and because in this state it cannot be admitted until it is, as it were, naturalized in the placenta.”

7

Like the Englishman Christopher Wren, for whom medicine and architecture were woven together in his plans for a new London, Perrault was similarly fascinated by the relationship between bodies and buildings. As the first to translate the works of the Roman architect Vitruvius into French, Perrault applied Vitruvian dictates of

firmatas, utilitas, venustas

(strong, useful, beautiful) to all that he did on behalf of the king, especially his anatomical work at the royal Academy of Sciences. For Perrault animal bodies had their own geometries, their own symmetriesâtheir own “architecture”âso much so that the physician often displayed his dissected creatures among the very buildings that celebrated the Sun King's reign.

However, unlike Wren, Perrault refused to link bloodâand especially heterogeneous tranfusionâwith sound architectural

design. “Just as the superior construction of a palace,” Perrault asserted, “cannot be affected except from materials cut and appropriate to its particular structureâ¦so the parts of each animal cannot be nourished except by blood which has been prepared by these very parts.” Perrault could not have been clearer about his disdain for transfusion in his architectural references: “The flesh of a dog cannot be nourished and repairedâ¦by the

blood of another dog, any more than the stone which is cut for an arch can serve either for the construction of a wall or even for another arch than that for which it was cut.”

8

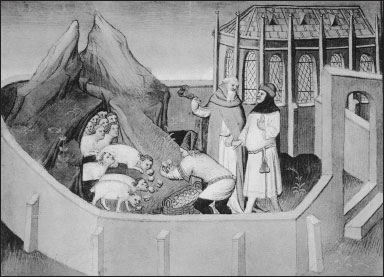

FIGURE 14:

Claude Perrault's monkeys, both live and dissected, with Versailles in the background.

Histoire Naturelle

(1676).

With the unyielding Perrault directing behind the scenes, the Academy of Sciences and the Paris medical facultyâPerrault was a member of bothâmade their stance against transfusion clear. And when Claude Perrault made up his mind, there was no doubting his determination. That was abundantly clear when the physician-architect designed an imposing triumphal arch in the Saint-Antoine quarter to honor Louis XIV. Perrault created an ingenious system of interlocking unmortared stonesâeach measuring nearly twelve feet high, four feet wide, and two feet deepâwhich were then meticulously polished until they were fused seamlessly together. The arch was, like Perrault himself, so stubborn that plans to demolish it decades later were nearly abandoned. In the end the entire structure had to be carted away intact.

9

THE PHILOSOPHER'S STONE

I

n his closing remarks on blood transfusion, Claude Perrault admonished the English by explaining that “the method employed by Medea to rejuvenate her father-in-law was less fabulous and more probable”

1

than the claims that had been made about transfusion. And by evoking Medea, Perrault neatly classified the new science of transfusion among the superstitions of past eras. Transfusion had long been associated with antiquity and, more precisely, Medea, the sensual, ravishing sorceress of Greek mythology.

Medea held seemingly limitless powers to seduce, to plotâand to kill. In one famous mythological scene, Medea commanded servants of King Pelias, her enemy, to bring her an old sheep. Knife in hand, she bled the limp beast nearly dry and cast it into a bubbling cauldron. Soon, a transformed young lamb leaped out of the cauldron. Impatiently she turned next to the king's daughters, who hovered in a drugged trance induced by the witch's herbs. On Medea's command, they pounced like ravenous beasts. Mimicking the sorceress's brutal and precise cuts,

the daughters deftly sliced open their father's veins and drained them dry. Medea fled the scene, smug with success at murdering Pelias secondhand.

For Medea transfusion was not just a form of deception. When the sorceress chose to allow it to work, it workedâmagically and miraculously. Using claims of transfusion to kill her husband's rival, she also used the real thing on his father, Aeson. She stirred together a brew of “a thousand things,” wrote Ovid, “and when Medea saw her brew was ripe,”

She flashed a knife and cut the old man's throat.

Draining old veins she poured hot liquor down

Some steaming through his throat, some through his lips

'Til his hair grew black and straight, all grayness gone.

His chest and shoulders swelled with youthful vigor

His wrinkles fell away, his loins grew stoutâ¦

And Aeson, dazed, remembered this new self

Was what he had been forty years ago.

2

Perrault may have scoffed at such tales of Medea's transformative magic, but stories of blood transfusion's metamorphoses were alive and well in the early European imaginationâand they drove an even-greater wedge into the already tense relationship between doctors and natural philosophers in Protestant England and Catholic France. The move to science from superstition was far from linear in what some now call, perhaps too reverently, the Scientific Revolution. In late-seventeenth-century Protestant England, science and alchemy were not distinct. The elusive quest for the philosopher's stoneâthe mystical chemical secret that could be used to transmute base metals into goldâwas considered the work of “chymists” and alchemists alike. In fact it was not unusual for books with titles like Michael Sendivogius's

New

Light on Chemistry

(

Novum lumen chymicum

) and other collections such as the

The Theaters of Chemistry

(

Theatra chemica

) to contain chapters on transmutationâthe calling card of alchemy. Yet if “chymistry” books often evoked transmutation, many “alchemy” books made, interestingly, no mention of the production of gold, as was the case with Andreas Libavius's

Alchemia

.

3

The “Father of Modern Chemistry,” Robert Boyle himself, claimed to have made progress in his efforts to produce “philosophical mercury,” a critical component for the creation of the philosopher's stone. At the age of forty Boyle still had a rosy, youthful face. He was a handsome man who, unmarried, preferred to spend most of his time in his laboratories at Oxford or in the experiment rooms he had set up in his sister's London home. There half-finished manuscripts and papers were strewn through his laboratory,

4

competing for space with balances, jars and vials, mortars and pestles, “weather glasses” (barometers) and “thermoscopes.” Bottles and handblown glass tubes cluttered the rows of shelves and tables that sat near the fireplace along with several alembics, used to distill the herbs and plants growing just outside in a small “physick garden.”

In his laboratory Boyle experimented withâamong other thingsâtransmutation. Breaking the code of silence that typically surrounded transmutation experiments, Boyle described how he purified a small amount of mercury by warming it and mixing it with gold. Writing in the

Philosophical Transactions

under the easily decipherable initials B. R., he explained how he placed a small amount of each in his palm and stirred the mixture delicately with his fingers. The concoction became “considerably hot” and within just one minute the gold dust had melted. Henry Oldenburg was among those who observed Boyle in his laboratory and, according to Boyle, confirmed “with his own hands” that the experiment was successful. Boyle's curious treatise on

philosophical mercury ended with an exhortation to readers not to push him for further details. He explained that he would “by all means avoid, for divers reasonsâ¦divers Queries and perhaps requests (relating to this Mercury).” The scientist later noted that his primary reason for not revealing the full secrets behind his work was that he was fearful of the “political inconveniences that might ensue if it shouldâ¦fall into ill hands.”

5

Still, Boyle wondered publicly whether transfusion might be another form of alchemical transmutationâa type of physiological philosopher's stone. In fact the transformative potential of blood transfusion could not have been more intellectually invigorating for the chemist Boyle. In a letter to Richard Lower that was later read before the Royal Society, Boyle drew up a list of sixteen queries, hoping that they would “excite and assist others in a matterâ¦to be well prosecuted.”

6

In it he acknowledged that the task of solving blood's greatest intellectual puzzles was just too monumental for one man to undertake without help and issued a plea in the

Philosophical Transactions

to other “learned persons” for assistance.

Of Boyle's sixteen questions, six pondered the impact of the procedure on the appetite of the recipient, an idea based on Lower's early theory that blood transfusion could provide a means for intravenous feeding. The remaining questions focused on possible experiments that would probe the full range of potential transmutations. Most notably, Boyle was interested in learning the extent to which blood transfer between beasts of different species would lead, or not, to an eventual change in an animal's behavior and appearance:

Whether by this way of transfusing blood, the disposition of individual animals of the same kind, may not be much altered? (As whether a

fierce

Dog, by being often quite new

stocked with blood of a

cowardly

Dog, may not become more tame; & vice versa?)

Whether acquired habits will be destroy'd or impair'd by this Experiment? (As whether a Dog, taught to fetch and carry, or to dive after Ducks, or to set, will after frequent and full recruits of blood of Dogs unfit for those Exercises, be as good at them, as before?)

What will be the [outcome] of frequently stocking (which is feasible enough) an

old

and feeble Dog with the blood of

young

ones as to liveliness, dullness, drowsiness, squeamishness, & vice versa?

Whether the

Colour

of the Hair or Feathers of the

Recipient

animal, by frequent repeating of this Operation, will be changed into that of the

Emittent

?

7

Boyle's proposals surrounding blood transfusion's transformative potential reflected a cultural fascination for hybrid beasts that had endured since antiquity. As early as the first century BC, Pliny the Elder compiled a lengthy encyclopedic account of more than forty different groups of odd and strangely spellbinding peoples. Among the lengthy list of “Plinian Races” were cannibals, troglodytes, and pygmies, as well as misshapen headless men with eyes on their chests. The Middle Ages inherited Pliny's catalog of races, embellishing them with new descriptions of mysterious peoples that were said to roam the earth. One of the best-known accounts came from Odoric of Pordenone, a fourteenth-century Italian traveler. Friar Odoric was dispatched to the East by the Franciscan Order on a mission to convert heathens to Catholicism. Curious and gifted with words, he documented his travels in the form of an adventure tale filled with amazing creatures. In the Nicobar Islands, he claimed to have met a well-dressed and

highly organized race of dog-faced people, the “cynocephali.” Odoric described his appreciation for their king, who “attends to justice and maintains it, and throughout his realm all men may fare safely.”

On an even stranger occasion during his travels, Odoric stopped to rest at a monastery nearer to China. After dinner, one of the monks cleaned the tables of scraps and invited the traveler to feed the animals who lived in the countryside. The two men strolled in the lush foothills. When they reached their destination the monk struck a gong loudly; at the sound the trees rustled, and “a multitude of animals” emerged from a nearby grotto. Odoric marveled at the “apes, monkeys, and many other animals having faces like men, to the number of some three thousand” that surrounded him. Laughing heartily, he asked his companion what these beasts were. The monk replied, “These animals be the

souls of gentlemen, which we feed in this fashion for the love of God.” Odoric quickly disagreed. “No souls be these, but brute beasts of sundry kinds.”

8

FIGURE 15:

Odoric of Pordenone's human-faced animals.

FIGURE

16: odoric of Pordenone's society of dog-faced men, the “cynocephali.”

Odoric's medieval claims for the existence of hybrid species joined other similarly detailedâand fancifulâaccounts by such travelers as Marco Polo, Sir John Mandeville, and many others. And if we are to believe early modern observers, equally strange “monsters” were just as likely to walk among Europeans as they were to haunt the high seas. In 1657 Royal Society fellow John Evelyn described a lovely harpsichord-playing maiden who was being exhibited, for a charge, throughout the city. Barbara Urselin was covered from head to toe with silky soft blond hair and, wrote Evelyn, “a most prolix beardâ¦exactly like an Iceland Dog.”

9

A hog-faced and cloven-footed gentlewoman named “Mistris Tannakin Skinker” had likewise made an appearance in London, ostensibly in search of a husband, just a few decades ear

lier. The pig-maiden had, it seemed, no luck in securing a willing groom and moved to France because “although she has a golden purse, she [was] not fit to be a nurse in England.”

10

FIGURE 17:

Barbara Urselin (née Vanbeck), a Very Hairy Woman

by Robert Gaywood (1656).