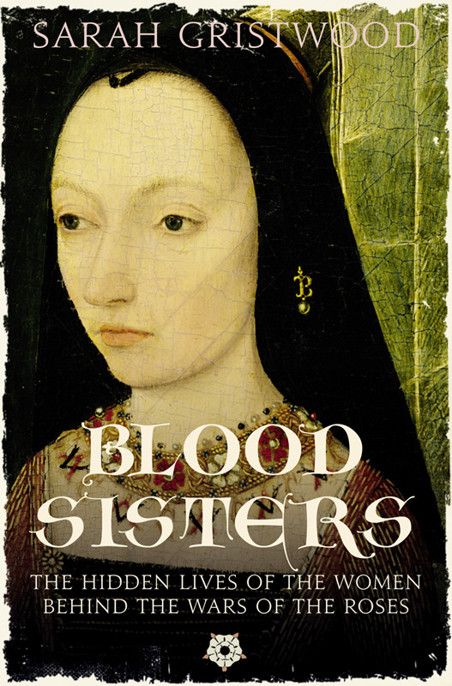

Blood Sisters

Authors: Sarah Gristwood

SARAH GRISTWOOD

Blood Sisters

The Hidden Lives of the Women

Behind the Wars of the Roses

CONTENTS

1

. Marguerite of Anjou with Henry VI and John Talbot in the ‘Shrewsbury Talbot Book of Romances’, c.1445. British Library, Royal 15 E. VI, f.2v (© The British Library Board)

2

. The stained-glass Royal Window in Canterbury Cathedral (© Crown Copyright. English Heritage)

3

. Margaret Beaufort by Rowland Lockey, late 16th century (By permission of the Master and Fellows of St John’s College, Cambridge)

4

. Margaret Beaufort’s emblems (© Neil Holmes/The Bridgeman Art Library)

5

. Cecily Neville’s father, the Earl of Westmoreland, with the children of his second marriage (Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris/Flammarion/The Bridgeman Art Library)

6

. Portrait of Elizabeth Woodville from 1463 (© The Print Collector/Corbis)

7

. Anne Neville depicted in the Rous Roll, 1483–85. British Library Add 48976 (© The British Library Board)

8

. King Richard III by unknown artist, oil on panel, late 16th century; after unknown artist late 15th century (© National Portrait Gallery, London)

9

. The risen Christ appearing to Margaret of Burgundy by the Master of Girard de Rousillon, from

Le dyalogue de la ducesse de bourgogne a Ihesu Crist

by Nicolas Finet, c.1470. British Library Add.7970, f.1v (© The British Library Board)

10

. Elizabeth of York by unknown artist, oil on panel, late 16th century; after unknown artist c. 1500 (© National Portrait Gallery, London)

11

. The birth of Caesar from

Le fait des Romains

, Bruges, 1479. British Library Royal 17 F.ii, f.9 (© The British Library Board)

12

. The Devonshire Hunting Tapestry – Southern Netherlands (possibly Arras), 1430–40 (© Victoria and Albert Museum, London)

13

. Procession at the Funeral of Queen Elizabeth, 1502 (© The Trustees of the British Museum)

14

. The preparations for a tournament. Illustration for René of Anjou’s

Livre des Tournois

, 1488–89? Bibliothèque nationale de France, Francais 2692, f.62v–f.63 (Bibliothèque nationale de France)

15

. Margaret of Burgundy’s crown, Aachen Cathedral Treasury (© Domkapitel Aachen (photo: Pit Siebigs))

16

. Song ‘Zentil madona’: from Chansonnier de Jean de Montchenu, 1475?, Bibliothèque nationale de France, MS Rothschild 2973, f.3v–f.4 (Bibliothèque nationale de France)

17

. The Tower of London from the Poems of Charles of Orleans, c.1500. British Library, Royal 16 F. II f.73 (© The British Library Board)

18

. Elizabeth of York’s signature on a page of ‘The Hours of Elizabeth the Queen’, c.1415–20. British Library Add 50001, f.22 (© The British Library Board)

19

. Wheel of Fortune illumination from the

Troy Book

, c.1455–1462. British Library Royal 18 D.II, f.30v (© The British Library Board)

Of the seven women whose stories I explore, the fashions of the times mean that two are called Elizabeth and three, Margaret. I have therefore referred to the York princess who married the Burgundian ruler as Margaret ‘of Burgundy’, while giving Margaret of Anjou the French appellation she herself continued sometimes to use after marriage – Marguerite. The family originally spelt as ‘Wydeville’ has been given its more familiar appellation of ‘Woodville’, and other spellings and forms have sometimes been modernised. The quotations at the top of each chapter have been drawn from Shakespeare’s history plays.

| Henry IV | 1399–1413 | Lancaster |

| Seized the throne from his cousin Richard II | ||

| Henry V | 1413–22 | Lancaster |

| Henry VI | 1422–61 | Lancaster |

| Succeeded to the throne before he was a year old, and at first ruled in name only | ||

| Edward IV | 1461–70 (first reign) | York |

| Seized the throne from Henry VI | ||

| Henry VI | October 1470–April 1471 | |

| (‘Readeption’) | Lancaster | |

| Edward IV | 1471–83 (second reign) | York |

| Edward V | April–June 1483 | York |

| Richard III | 1483–85 | York |

| Henry VII | 1485–1509 | Lancaster |

| Henry VIII | 1509–47 | Tudor |

She had died on her thirty-seventh birthday and that figure would be reiterated through the ceremony. Thirty-seven virgins dressed in white linen, and wreathed in the Tudor colours of green and white, were stationed in Cheapside holding burning tapers; thirty-seven palls of rich cloth were draped beside the corpse. The king’s orders specified that two hundred poor people in the vast and solemn procession from the Tower of London to Westminster should each carry a ‘weighty torch’, the flames flickering wanly in the February day.

1

For Elizabeth of York had been one of London’s own. Her mother Elizabeth Woodville had been the first English-born queen consort for more than three centuries, but where Elizabeth Woodville had been in some ways a figure of scandal, her daughter was less controversial. She had been a domestic queen, who gave money in return for presents of apples and woodcocks; and bought silk ribbons for her girdles, while thriftily she had repairs made to a velvet gown. Elizabeth rewarded her son’s schoolmaster, bought household hardware for her newly married daughter, and tried to keep an eye out for her sisters and their families. The trappings of the hearse showed she was a queen who had died in childbirth, a fate feared by almost every woman in the fifteenth century.

She had been, too, a significant queen: the white rose of York who had married red Lancaster in the person of Henry VII and ended the battles over the crown. Double Tudor roses, their red petals firmly encircling the white, were engraved and carved all over the chapel where she would finally be laid to rest.