Blood River (27 page)

Authors: Tim Butcher

`Get away, get away,' Michel shouted at me. I had heard stories

of Congolese ant columns descending on villages and eating

everything in their path. Infants, the elderly and the infirm will

perish if left to be consumed by the column. A hunter told me that

he would prepare the trophy from an antelope hunt by deliberately finding one of these ant columns and then throwing the

dead animal's skull into its path. When he came back the next

day, the bone would be spotless, stripped of every last piece of

flesh and gristle, tendon and tissue.

Stupidly ignoring Michel, I approached to what I took to be a

safe distance and started taking photographs. Within seconds I

had a bite on my knee, and then one on my thigh, then another on

my back. As I ran back to the bikes, the ants were so thick on my

trousers I brushed them off like soot. It took ten minutes to

undress and rid every last ant from the creases in my clothes. The

worst of the bites stung for days.

From time to time we would spot other road users, pedestrians

carrying heavy loads or pushing bicycle frames laden with food.

Just as earlier on my trip, these people carried possessions that

belonged not to today's world, but to an earlier time. Loads were

wrapped in old leaves and then bundled up with woven grass

into primitive rucksacks carried on a headstrap reaching round

the forehead. Several of the walkers had large African snails stuck

to the side of their leaf bundles. The snails did not have to be tied

on, as their gooey, muscular foot kept them firmly attached until

the moment when they were taken off and cooked. The only other

food we saw was cassava paste tied in small rectangular leaf

packets. Cassava smells pretty rich even when it has just been

cooked, but this stuff was even more rank having been carried for

days, unrefrigerated, along the sweaty jungle floor.

I saw a husband and wife plodding along at the pace of one of these mealtime snails. Both were carrying heavy loads borne on

headstraps of fibrous bark reaching under the baskets and then

around their foreheads. They were sweating heavily and after I

persuaded Michel to stop, I took a hold of the man's basket. I

could barely lift it and he was carrying it for 143 kilometres, the

distance clocked by my bike's odometer between Ubundu and

Kisangani, with the entire weight borne by his neck.

I asked the man about an atrocity that happened on this very

track in early 1997. Thousands died when a column of Hutu

refugees from Rwanda was attacked by rebel forces loyal to the

new Tutsi regime in Rwanda. For a few weeks around the end of

March and beginning of April, aid workers described what

happened here as one of Africa's worst war crimes. I wanted to

know what impact it had had on the local community.

The man listened to my question and thought for a moment

before shaking his head.

'I come from Ubundu, but I don't know what you are talking

about. There have been many attacks and many massacres. When

it happens we flee into the bush, but nobody ever knows the

details.'

I was stunned. An hour later we stopped in a trackside village

called Obila. The IRC maintained a solar-powered fridge there

inside a thatched hut to preserve vaccines and medicines, which

are given out at a clinic of other thatched huts. Again, I asked

about the 1997 massacre. Again, my question was met with

shrugs.

It taught me a lesson about one of the Congo's chronic

problems, its lack of institutional memory. The loss of life during

the slaughter on the Ubundu-Kisangani road was of the same

order of magnitude as the 11 September 2001 attacks in the

United States, and yet in the Congo there were no repercussions.

There was no memorial, or historical account of what happened,

or court case to hold the perpetrators to account, or international

response. The killings simply got lost in the Congo's miasma of misery. I wondered what hope there can be for a place if such

lessons from the past are never heeded.

It was during this part of the journey that I had one of my most

profound Congolese experiences. Since we left Ubundu several

hours earlier we had seen nothing but forest, track and the

occasional pedestrian or thatched hut. The scene I saw in the

twenty-first century was no different from that seen by Stanley in

the nineteenth century or by pygmy hunter-gatherers over earlier

centuries. It was equatorial Africa at its most authentic, seemingly

untouched by the outside world.

Suddenly, our convoy stopped. One of the bikes needed

refuelling, or one of the riders had taken a tumble, I don't remember. What I do recall was the sense of Africa at its most brooding.

The engines had been switched off and the silence was absolute.

There was no birdsong, no screech of monkeys. Everything edible

had long since been shot or trapped for the pot by local villagers,

and the thick canopy way above our heads insulated us from any

sounds of wind swishing branches or rustling leaves.

The ground was brown with mud and rotting vegetation. No

direct sunlight reached this far down and there was a musty smell

of damp and decomposition. Above me towered canyons of

green, as layer after layer of plant life filled the void between

forest floor and treetop. I felt suffocated, but not so much from the

heat as from the choking, smothering forest.

I took a few steps and felt my right boot clunk into something

unnaturally hard and angular on the floor. I dug my heel into the

leaf mulch and felt it again. Scraping down through the detritus,

I slowly cleared away enough soil to get a good look. It was a castiron railway sleeper, perfectly preserved and still connected to a

piece of track.

It was a moment of horrible revelation. I felt like a Hollywood

caveman approaching a spaceship, slowly working out that it

proved life existed elsewhere in time and space. But what made it so horrible was the sense that I had discovered evidence of a

modern world that had tried - but failed - to establish itself in the

Congo. It was a complete reversal of the normal pattern of human

development. A place where a railway track had once carried

trainloads of goods and people had been reclaimed by virgin

forest, where the noisy huffing of steam engines had long since

lost out to the jungle's looming silence.

It was one of the defining moments of my journey through the

Congo. I was travelling through a country with more past than

future, a place where the hands of the clock spin not forwards, but

backwards.

The railway track belonged to the Equator Express, a line built

by the Belgians to circumvent the Stanley Falls, cutting straight

through the Equator. Katharine Hepburn described taking the

train to The African Queen set, and the grim conditions during

the eight hours it took the train to cover just 140 kilometres.

Some of the film crew members tried to deal with the heat by

pouring buckets of water over themselves, but she judged it a

waste of time because the effort of raising the bucket made you

sweat even more, so she sat in a puddle of inertia willing the

journey to end.

I heard a rumour that an enterprising Belgian official had

placed a plaque alongside the rails to mark the exact spot where

they cut the Equator. I would have liked to have tried to find the

sign, but our bike track had deviated far from the overgrown railway line at the relevant place. I had to make do with holding my

GPS device in my hand as I bumped along behind Michel on his

motorbike and praying that it would work. I had used it to follow

my journey from Kalemie, six degrees south of the Equator, and

wanted to know the exact spot where I would cross from South to

North. But to function it needed to pick up signals direct from a

satellite and the thick tree cover meant the machine had trouble

registering a signal. I cursed.

Then all of a sudden we reached an opening in the tree canopy

and a clearing on the ground for a village. The machine pinged

into life and the screen registered a long line of noughts. I was

smack on the Equator on the noughth degree of latitude. I tapped

Michel on the shoulder and asked him to stop so that I could find

out the name of the village, Batianduku, which enjoys the status

of straddling the Equator and being in both the northern and

southern hemispheres.

The journey continued with the same rhythm of all my

Congolese motorbike experiences. I would peer over the shoulder

of the rider, trying to read the track so that I could brace myself

for the next pitch forward or lurch to one side, through a blurred

tunnel of forest green whipping past the periphery of my vision.

Green, green, green, broken only occasionally by the brown of

mud huts in a village clearing before more green, green, green.

The odometer on the bike's handlebars counted down the kilometres to Kisangani, but the more I stared at it, the slower it

seemed to move. In the end I stopped looking, my mind too numb

to care.

And then, with a rush of light, the forest curtain was lifted and

we reached one of the great jungle cities of Africa. Initially I felt

excited, but disorientated. The buildings, the wide roads, the

crowds of people and moving cars made me feel a little giddy.

Kisangani was built mainly on the right (eastern) bank of the river

and our track had brought us to the less-developed left bank.

Pirogues ferried people backwards and forwards and these were

special pirogues, very different from the ones I had used

upstream, because they had outboard motors.

The sun was setting behind us by the time we had found one to

ferry our bikes across the Congo River and, with the sun on my

back, I had time to prepare myself for the big city. It felt like a

moment of discovery. After weeks of mud huts, jungle tracks and

hollowed-out canoes, I had found a pocket of modernity. The city

docks glowed in the soft light to reveal a line of crane gantries on the wharf, an impressive cathedral with twin towers, a miniature

version of Notre-Dame, and even some high-rise buildings. And

in my pocket my mobile phone chirruped back into life.

Bend in the River

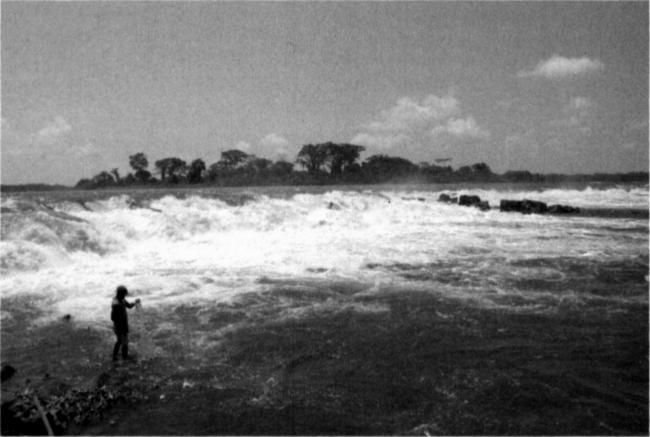

THE SEVENTH CATARACT, STANLEY FALLS.

Final cataract in the Stanley Falls as recorded, above, by H.M. Stanley in

1878 and, below, by the author in 2004

My euphoria at reaching Kisangani did not last long. The gentle

sunset on that first evening might have given it the appearance of

a regular city, but as I explored I found it to be a shell, prone to

spasms of brutal anarchy and chaotically administered by inept,

corrupt local politicians. And it owed what little stability it had

to the artificial props of a large UN force and foreign aid workers.

For the first days I was in recovery mode. I checked into the

most lavish hotel the town could offer, the Palm Beach, which at

$75 a night gave me comforts I had not enjoyed for weeks: a bed

with laundered sheets, a shower, a door with a lock. It was built

at the end of the Mobutu era and was already more than ten years

old, but the two-storey structure was the most modern in the city.

Skirmishes during the wars following Mobutu's death had

imbued the hotel with quite a reputation - the bodies of eleven

Ugandan soldiers killed in the grounds were stored for days in a

bathroom because the kitchen refrigerator had been destroyed,

and I kept hearing sketchy and unverifiable accounts of a foreign

journalist whose dead body had recently been discovered in one

of the rooms.