Blood of the Isles (10 page)

Read Blood of the Isles Online

Authors: Bryan Sykes

It took another two decades until his prize essay, plus the additional material he had acquired in the meantime, eventually appeared in book form. It was published as

The Races of Britain

in 1885. By then a Fellow of both the Royal Society and the Royal College of Physicians, the publication of

The Races of Britain

brought Beddoe fresh honours and fresh activity. In 1891 he retired from his Bristol medical practice and moved to the nearby town of Bradford-on-Avon. Even this move could not interrupt the flow of honours and invitations, and in 1905, now aged seventy-nine, he gave the annual Huxley Lecture for the Royal Anthropological Institute. He died six years later, the year after publishing his autobiography,

Memories of Eighty Years

. In the copy in front of me as I write, the sepia photograph of the frontispiece, protected by a thin sheet of tissue paper, shows an old man with a full white beard, dressed in a three-piece suit and standing confidently, legs slightly

apart, on the broad front step of his stone house. One hand in his pocket, the other on a stout pole, his chained watch just visible in his waistcoat pocket, he peers into the distance with dark eyes. Eyes that had inspected and recorded the faces of thousands upon thousands of the people of the Isles. Underneath is his signature, in jet-black ink, not faded by the years. John Beddoe. The two ‘d’s are a little shaky, but the flourish at the end is not. It is strange to think that the hand that signed this copy, nearly 100 years ago, was the same that marked the cards he carried with him throughout his journeys.

The real meat of Beddoe’s lifetime of observation lies in the tables and maps that make up about half of the 300 pages of

The Races of Britain

. He visited and recorded in 472 different locations throughout Britain and Ireland, making a total of 43,000 observations. The tables themselves are delightfully annotated with asides such as ‘Cornwall, St Austell. Flower show. Country folk’ or ‘Bristol. Whit-Monday. Young people numerous. Dancing.’ He also got hold of a further set of 13,800 observations from the unlikely source of the lists of army deserters whose pursuers published their physical description in the chillingly titled periodical

Hue and Cry

. Finally, he recorded his own patients as they came through his Bristol surgery – a total of 4,390 altogether. These were particularly precious because there was time to make accurate observations and to check on the birthplace of each patient.

Beddoe was very well aware of the dangers of unrepresentative sampling, and of more subtle influences on the accuracy of his record. For example, were his Bristol

patients representative of the general healthy population? Possibly not. They must have had a reason to be in his surgery in the first place. Indeed, he notes that the incidence of disease among American army recruits was reported to be much higher among the ‘dark complexioned’. And his patients did, when averaged out, have a slightly higher Index of Nigrescence than the West Country folk that he observed in streets and marketplaces. This discrepancy he puts down to differences of moral character, allying cheerfulness and an optimistic outlook to a light complexion, while ‘persons of melancholic temperament (and dark complexion) I am disposed to think, resort to hospitals more frequently than the sanguine’. Even then, blondes had more fun.

The Races of Britain

was, and still is, a masterpiece of observation. The samples were not statistically controlled, his coverage of Britain and Ireland was not uniform, and he came in for criticism on these grounds – rather predictably from people who never themselves got into the field. But his work is best judged as a masterly piece of natural history and not a modern work embroidered with statistical treatments.

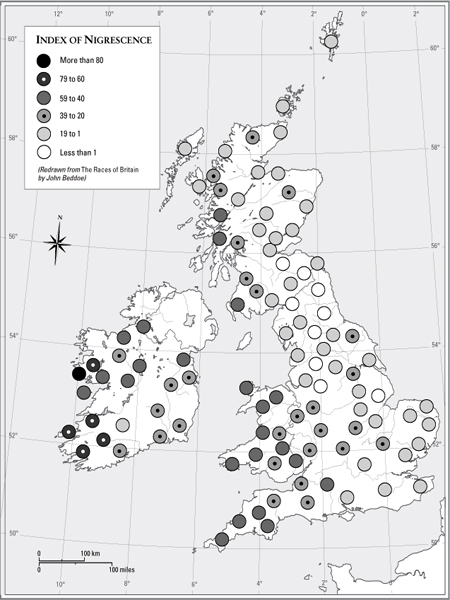

So what of the results themselves, and what did they tell Beddoe, and us, about the origins of the people of the Isles? Taking his measurements of hair colour and applying the formula of the Index of Nigrescence across the whole of Britain and Ireland, the values range from 0 to 80. There is a very clear difference between the far east of Britain, by which I mean East Anglia and Lincolnshire, where the Index is lowest, and Ireland and Cornwall in the west,

where it reaches its highest value, as it also does in the west of Scotland. The low values for East Anglia are also continued across Yorkshire and Cumbria and again in the far north of Scotland and the Hebrides. In all these regions the Index is about zero, which means, in practice, that there are as many blondes and redheads as there are brunettes. In other parts of England, and in Wales, the values for the Index are intermediate between the fairer east and the darker west.

The Index is a measure of hair colour alone. When it comes to eye colour, the east–west gradient is reversed. Brown eyes are commonest in the east and south, where they exceed 40 per cent in East Anglia, but also in Cornwall. In Ireland, but also in Yorkshire and Cumbria, the same counties where red/fair hair were at their highest proportion, the number of people with blue or grey eyes rises to 75 per cent. In the far north of Scotland and the Hebrides, where fair hair was common, blue or grey eyes are even commoner than they are in Ireland. When hair and eye colour are combined to produce two basic types – what Beddoe calls ‘Mixed Blond’ and ‘Mixed Dark’ – with fair/red hair and blue/grey eyes or dark eyes and dark hair respectively – the patterns reflect the individual components to some extent. ‘Mixed Blonds’ outnumber their opposites in the north of Scotland, east Yorkshire and Lincolnshire, while ‘Mixed Darks’ predominate in Wales, Cornwall and the Scottish Highlands, along with Wiltshire and Dorset. In Ireland, especially in the west, the Mixed Blond outnumber the Mixed Dark, leading to the conclusion, when coupled with the high Index of Nigrescence,

that there must be a high proportion of dark-haired people with blue or grey eyes.

Beddoe begins his conclusions in the far north. ‘The Shetlanders’, he says, ‘are unquestionably in the main of Norwegian descent, but include other race elements also.’ He draws the same conclusion for the inhabitants of Orkney and of Caithness in the far north of the Scottish mainland. He assumes the Norwegian element came with the Vikings. He also makes the strange observation that ‘The excessive use of tea, the one luxury of Shetland, probably only aggravates a constitutional tendency to nervous disorders which is more prevalent among the few dark than the many fair Shetlanders.’ This is the point to tell you that Beddoe describes himself as a young man ‘of fair complexion, with rather bright brown wavy hair, a yellow beard and blue eyes’. Clearly it was perfectly safe for him to drink the tea.

As he works his way down Britain and across to Ireland, his observations combine preconception with perception in an extraordinarily personal record of his encounters. On Lewis, in the Western Isles, he observes the ‘large, fair and comely Norse race, said to exist pure in the district of Ness at the north end of the island’ and the ‘short, thick-set, snub-nosed, dark-haired, often dark-eyed race, probably aboriginal and possibly Finnish whose centre seems to be in Barvas’. Barvas is 12 miles north-west of the principal town, Stornoway.

Beddoe is acutely aware of influences on the objectivity of his observations. In recording the Highlanders he says at once that ‘Most travellers, on entering the habitat of a race

strange to them quickly form for themselves from the first person observed some notion of the prevailing physical type.’ Also he is aware that the longer he spends in a particular place, the more he can distinguish the differences between people: ‘I confess that the longer I have known the Scottish Highlanders the more diversity I have seen among them.’

He also notices the presence of what he calls ‘a decidedly Iberian physiognomy, which makes one think . . . that the Picts were in part at least of that stock’. We will return to that particular element of the British mix later in the book. As he crosses the border into England he finds pockets of ‘a very blond race in Upper Teesdale’ and, further south, ‘the small, round-faced dark-haired men with almond-shaped eyes . . . in the vale of the Derwent and the level lands south of York’, which he ascribes to either an Iberian or Romano-British origin. There is a growing feeling, as Beddoe moves around the country, that he is forming the view that dark-eyed and dark-haired people are the remnants of the indigenous Britons that were later supplemented, or displaced, by the Saxons and the Vikings. Even as he travels to the West Country, the connection is there: ‘In the district about Dartmouth, where the Celtic language lingered for centuries, the Index of Nigrescence is at its maximum.’ Onward to Cornwall, where ‘The Cornish are generally dark in hair and often in eye: they are decidedly the darkest people in England.’

When Beddoe moves into Wales, he finds in the central region ‘a prevalence of dark eyes beyond which I have met with in any other part of Britain’. The Snowdonians too are

‘a very dark race’, while around the coast eyes and hair are lighter. Across the Irish Sea, he records that ‘the frequency of light eyes and of dark hair, the two often combined, is the leading characteristic’.

So much for the observations. What about the conclusions? There can be a tendency among collectors to leave interpretation of their results to others, mainly, I think, for fear of being proved wrong and thus undermining their whole legacy. This is an increasing trend, but even Beddoe was shy of absolute conclusions. None the less he ventured an explanation for the fair-haired people of England, suggesting that ‘the greater part of the blond population of modern Britain . . . derive their ancestry from the Anglo-Saxons and Scandinavians . . . and that in the greater part of England it amounts to something like half’. So there we have it. Beddoe explains the different colouring by a very substantial settlement from Saxon, Dane and Viking. The particularly light colouring in parts of Yorkshire, which we noted previously, he attributes to the impact of the Norman Conquest. However, Normans, as we will later discover, are really no more than recycled Vikings. On Ireland and the Gaelic west generally, Beddoe thought the people to be a blend of Iberians with ‘a harsh-featured, red-haired race’. The Celtic ‘type’, with dark hair and light eyes, he ventures to suggest, may only be an adaptation to the ‘moist climate and cloudy skies’ which they endure.

Beddoe concludes the account of his lifetime’s work with this paragraph:

But a truce with speculation! It has been the writer’s aim rather to lay a sure foundation whereon genius may ultimately build. If these remaining questions are worthy and capable of solution, they will be solved only by much patient labour and by the co-operation of anthropologists with antiquarians and philologists; so that so much of the blurred and defaced prehistoric inscription as is left in shadow by one light may be brought into prominence and illumination by another.

It is as if John Beddoe, criss-crossing the country with card and pencil in hand, calipers and tape in his knapsack, had already anticipated the arrival of genetics. How he would have loved to be alive now.

Beddoe and his contemporaries were the first to substitute observation for deduction and prejudice in exploring the origins of the people of the Isles. But, as he himself freely admits, there was still a strong subjective element in his observations of appearance. After all, our obsession with looks is ample proof of its emotional influence. It must have been almost impossible for Beddoe not to have nurtured some preconceived ideas, which, with the best will in the world, will have influenced his conclusions.

The next stage in the scientific dissection of our origins removed this subjective element completely. It began a long way from England, just as John Beddoe was enjoying a comfortable old age and the flood of honours which acknowledged the fruits of his lifetime’s passion. While he posed for the frontispiece of

The Races of Britain

on the

doorstep of his comfortable mansion in the early years of the last century, a scientist in Vienna was mixing the blood of dogs.

THE BLOOD BANKERS

If you have ever been a blood donor, or ever needed a transfusion, then you will know your blood group. You will know whether you belong to Group A, B, O or even AB. The reason for testing is to avoid a possibly fatal reaction if you were to be transfused with unmatched blood. You cannot tell, just by looking, what blood group a person belongs to. Unlike hair and eye colour or the shape of heads, blood groups are an invisible signal of genetic difference which can be discovered only by carrying out a specific test.

Though the first blood transfusions were performed in Italy in 1628, so many people died that the procedure was banned. As a desperate measure to save women who were haemorrhaging after childbirth, there was a revival of transfusion in the mid-nineteenth century. Though some patients had no problems accepting a transfusion, a great many patients died from their reaction to the transfused blood. What caused the reaction was a mystery.

The puzzle was eventually solved in 1900 by the

Austrian physiologist Karl Landsteiner. After experimenting with mixing the blood of his laboratory dogs and observing their cross-reactions, he began his work on humans. He mixed the blood of several different individuals together and noticed that sometimes when he did this the red blood cells stuck together in a clump. This did not happen every time, but only with certain combinations of individuals. If this red-cell clumping was occurring in transfused patients, the blood would virtually solidify, which would explain the fatal reaction. It also explained why some patients tolerated a transfusion and showed no signs at all of a reaction.