Blood-Dark Track (2 page)

Authors: Joseph O'Neill

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #General, #Personal Memoirs, #Literary

– W. B. Yeats, ‘Hound Voice’

Preface to the Vintage Edition

Blood-Dark Track

, published in 2001, describes the inquiry I undertook into the history of my family, Irish and Turkish, from 1995 to 2000. The inquiry was propelled by my curiosity about the unexplained incarcerations of both my grandfathers during the Second World War, a private oddity that, looked into, gave entry to obscure, sometimes frightful parishes of Irish and Middle Eastern history. These places had an essentially, or especially, imaginary quality to a visitor from my situation, which is to say, a Westerner at the twentieth century’s end whose freedom from geopolitical upheaval and its connected dangers and responsibilities seemed as complete as possible. We know what happened next.

As its text makes clear,

Blood-Dark Track

was written by a practicing lawyer. My work as a London barrister came to an indefinite end by 2001, by which time I had lived in the United States for about three years. I was in New York City on September 11th, 2001. That day and its consequences made up an ingredient of the book I wrote after

Blood-Dark Track

, a work of fiction titled

Netherland

and identified by some as a ‘9/11 novel.’ I have no quarrel with this tag, even assuming that I have a quarreler’s standing, which is doubtful. But I will allow myself to state that, if I have written a ‘9/11’ book, that book would, in my mind, be

Blood-Dark Track

.

This edition is dedicated to the memory of my beloved grandmother, Eileen O’Neill.

West Cork

Turkey/Syrian border, Spring 1942

Prologue

For me it began in far-off Mesopotamia now called Iraq, that land of Biblical names and history, of vast deserts and date groves, scorching suns and hot winds, the land of Babylon, Baghdad and the Garden of Eden, where the rushing Euphrates and the mighty Tigris converge and flow down into the Persian Gulf.

It was there in that land of the Arabs, then a battle-ground for the contending Imperialistic armies of Britain and Turkey, that I awoke to the echoes of guns being fired in the capital of my own country, Ireland.

– Tom Barry

, Guerrilla Days in Ireland

A

t some point in my childhood, perhaps when I was aged ten, or eleven, I became aware that during the Second World War my Turkish grandfather – my mother’s father, Joseph Dakad – had been imprisoned by the British in Palestine, a place exotically absent from any atlas. A shiver of an explanation accompanied this information: the detention had something to do with spying for the Germans. At around the same age, I also learned that my Irish grandfather, James O’Neill, had been jailed by the authorities in Ireland in the course of the same war. Nobody explained precisely

why, or where, or for how long, and I attributed his incarceration to the circumstances of a bygone Ireland and a bygone IRA. These matters went largely unmentioned, and certainly undiscussed, by my parents in the two decades that followed. Indeed, the subject of my late grandfathers was barely raised at all and, save for a wedding-day picture of Joseph and his wife, Georgette, there were no photographs of them displayed in our home. Dwelling in the jurisdiction of parental silence, my grandfathers remained mute and out of mind.

Partially as a consequence of this, it was not until I was thirty that the curious parallelism in my grandfathers’ lives struck me with any force and that I was driven to explore it, to fiddle at doors that had remained unopened, perhaps even locked, for so many years; and not until then that I began to make out what connected these two men, who never met, and these two captivities – one in the Levant heat, the other in the rainy, sporadically incandescent plains of central Ireland.

As will soon become apparent, I wasn’t bringing a reflective political mind to bear on my grandfathers’ lives, or any expertise as a historian, or even any abnormal inclination to wonder about what might lie behind a closed door. In general, I’m as content as the next man to proceed on the footing that any information of importance – anything that has a bearing on my essential interests – will be brought to my attention by those entrusted with such things: families, schools, news agencies, subversives. This is so even though the information I have on most historical and political subjects could be written out on a luggage tag; is almost certainly wrong; and, at bottom, probably functions as a political soporific – which perhaps explains why the insights I gained into my grandfathers’ lives often took the form of a slow, idiotic awakening. It took anomalous forces – a writer’s professional curiosity turned into something like an obsession – to push me, reluctant and red-eyed and stumbling, into the past and, it turned out, its dream-bright horrors.

Two inklings set me on my way, one for each grandfather.

My Turkish grandmother, Mamie Dakad –

mamie

being French for granny – had an extreme attachment to a set of keys. She clung

to them from morning till night and then, secreting them under her pillow, from night till morning. When she mislaid them, all hell broke loose, in multiple languages. She would shriek first at herself in Arabic (‘

Yiii!

’), next at her family, in French (‘

Où sont mes clefs?

’), and finally – with terrifying loudness and venom – at the nearest servant, in Turkish: ‘

ANAHTARLAR NERDE?

’ The loss of keys was not the only thing that would set her off. My grandmother yelled frequently and for a whole variety of reasons at the waiters, maids, managers, cleaners and cooks whom she employed to staff her hotel and to attend to her personal needs and the needs of her family. All day they scurried in and out of her apartment in a sweat, delivering panniers of toast, bars of goat’s cheese, lamb cutlets, fish, aubergines, meat pancakes, melons, watermelons, water, glasses of lemonade, bottles of Efes beer, sodas, Coca-Colas, Turkish coffees, Turkish teas. You could never have enough to drink. Mersin, the port in south-east Turkey where my grandmother lived, is as humid a spot as you’ll find in the Mediterranean, and in August, when my parents and their four children arrived for their annual holiday, my grandmother’s breezeless apartment on the top floor of the hotel was as hot as a hammam. Fans vainly circulated warm air, and the trickle of coolness produced by the grinding air-conditioning machine escaped ineffectually through the windows towards the harbour, where Turkish warships sat on the still water like cakes on a salver. When we were not immobilized on the divans, pooped out, stunned, minimizing our movements, we were opening one of the refrigerators – the doors, tall as ourselves, swung out with a gasping, rubbery suck – and taking long, burning slugs of the freezing water that filled the Johnnie Walker and Glenfiddich bottles jammed in the rack. My grandmother’s outbursts were all the more terrible for their suddenness and unfairness, the minor domestic booboos, if any, from which they sprang (a fork misplaced in a drawer filled with Christofle silver, a floor-mopping delinquency) shockingly disproportionate to the condemnation that followed. I have never really understood why she was prone to these authoritarian rages. She was loving and unstinting with her friends and family and, it so happens, a loyal

employer. Perhaps the heat played a part, and racial and class contempt. Either way, Mehmet Ali, Mehmet, Huseyin, Fatma and the rest of them got it in the neck.

As I said, Mamie Dakad carried a bunch of keys about her person at all times. She never jingled them or fixed them to a pretty ring. She strung them around a bare loop of metal and gripped them – even in her old age, when arthritis had curled her fists into strengthless talons.

One morning, in a summer of the late ’eighties, when I was in my mid-twenties, there occurred an episode which might have belonged to a kids’ mystery story. My cousin Phaedon (the son of my mother’s sister, Amy) and I decided to take a look around a storage room in the hotel known as the depot. We knew that family stuff was kept there and we were curious. So we asked our grandmother for the key to the depot.

‘Why?’ she asked. She was getting her hair cut as she sat in the hot dining room, a white towel over her shoulders, a spectacular length of ash hanging crookedly from a butt in her mouth. Even though she was nearing the end of her career as a smoker (forty years of seeing off at least forty, preferably extra-strong Pall Mall, non-filters a day), she was still able to suck back an entire cigarette without touching it with her fingers.

I explained why. Mamie Dakad looked at me sceptically, then wordlessly pointed at her keys, which lay on a nearby table. I brought them to her. She plucked out a skeleton key. ‘Bring it back,’ she said.

We walked down the long corridor outside Mamie Dakad’s apartment. Ashtrays filled with sand were fixed to the walls, and dead, half-buried cigarettes protruded from the sand. The depot was half way down the corridor, next to the staircase that led to the roof of the hotel. From that scorching roof you saw, heaped on the northern horizon, the cool Taurus Mountains, whose name, spelled in phonetic Turkish, my grandfather Joseph gave to the hotel: the Toros Otel.

The depot was a stale, hot space overlooking the hotel’s oven-like internal yard. We found neat piles of sea-stained old paperbacks

from the ’seventies; snorkels; junior-sized flippers; my mother’s schoolbooks and school reports. Then I noticed, on top of a trunk, some papers held together by a large, rusting safety-pin – sixty or so pages extracted from a ledger book, with columns for debits and credits and totting up. But if this was an accounting, it wasn’t of the financial kind. In place of figures, lines of elegant manuscript Turkish filled the pages.

Phaedon took a look while I peered over his shoulder. After a minute or so, he said that the writing had to be our grandfather’s. It was an account, Phaedon said slowly, of his arrest, in 1942, and his subsequent imprisonment. We looked at each other. We knew we were entering, maybe trespassing on, a dark corner of the family history. Then we read on. Flicking quickly through the pages, Phaedon reported the main features of the story as best as he could; he had difficulty in understanding the old-fashioned, Arabic-influenced Turkish.

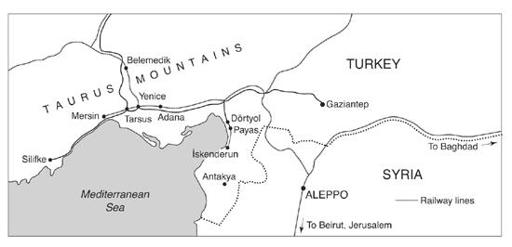

What Phaedon said was this: in March 1942, my grandfather went to Palestine on a business trip. He spent some time in Jerusalem, where he associated with Palestinian Arabs and a female acquaintance. On his way home, he was arrested at the Turkish–Syrian border by the British. He was taken to Haifa and then to the British headquarters in Jerusalem, and then detained elsewhere for the rest of the war. Phaedon couldn’t figure out what the exact nature of the document was. ‘It seems to be addressed to the Turkish authorities,’ he said with a shrug.

By the time we returned to Mamie Dakad’s apartment, the hairdresser was clearing up and my mother was laying the table for lunch for twelve: chicken, stuffed peppers, tabbouleh, cucumber and watercress salad with a lemon dressing, beans, lentils with rice, yoghurt, bread. A rubble of watermelons, grapes and peaches was piled up in the kitchen. For my grandmother and the community she belonged to, nothing, not even cards, was of greater social importance than food.

When I broke the news of our scoop to my mother, she reacted in a curious way; that is, apart from a raising of her eyebrows, she did not react. Almost as if she hadn’t heard me, she continued to set out

the forks and knives. Unabashed and excited, I turned to my grandmother and asked about the document. ‘Don’t speak about it,’ my mother said sharply to me in English, which was not one of Mamie Dakad’s languages, ‘it’ll upset her.’ It was too late. My grandmother was already in tears. ‘

Le pauvre

,’ she said, her face wrinkling and her hand raised in a distressed gesture of explanation, ‘

le pauvre, il a beaucoup souffert

.’

‘You see?’ my mother said. ‘You see what you’ve done?’

I returned the key to Mamie Dakad. Joseph Dakad’s papers were locked away once more, not to be seen again until years later.

My first moment of access to the life of my Irish grandfather, Jim O’Neill – and my first clue as to what may have formed his life’s hard, insubstantial heart – was also fortuitous. It took place in The Hague, the city where, in 1970, after series of migrations that had bounced us like a skipping roulette ball through South Africa, Mozambique, Syria, Turkey and Iran, my family came to a permanent halt. In the top shelf of the bookcase in the dining room was a hardback entitled

Letters of Fyodor Dostoevsky

. Although as a teenager I’d read most of my parents’ books, I’d never been enthused by this one. It had an uncompromising black cover and an unappetising introduction by one Avrahm Yarmalinsky, and Dostoevsky himself, the balding, anxious man in the jacket photograph, whose writing I had not read, did not look like a lot of fun. The Hague, however, is an uneventful place, and eventually I found myself idly leafing through the

Letters

; and I encountered, trapped in the book’s thick pages, two newspaper clips.