Blood Brotherhoods (50 page)

Read Blood Brotherhoods Online

Authors: John Dickie

Maria Marvelli’s story is but an isolated tableau of the piecemeal changes happening in Calabrian organised crime: the marriage politics that the

picciotti

were learning, and the new power behind the scenes that some women gained as a result. Marvelli was, without doubt, a loser: her house had been torched; her husband murdered. She lost her son too: despite his confession, the boy who had once been the most eligible criminal batchelor in Cirella was sentenced to six years and eight months under new, tougher Fascist laws against criminal associations. It is not known whether he was among

the men who had their toenails extracted by the

Carabinieri;

it is not known what happened to him in prison.

But Maria Marvelli did at least have something to put in the scales to counterbalance her losses. The satisfaction of vendetta, for one thing. And even some money: she sued the defendants on her children’s behalf, and won 26,000 lire—roughly equal to the value of her house.

We do not know what happened to Maria Marvelli later. She is like thousands of other faceless mafia women in history, in that we can only wonder what became of her after the court records fall silent. If she did go back to Cirella, she would certainly have found a village still in the grip of the picciotteria. The same judge who was too timid to confront the

Carabinieri

about their repeated assaults on the prisoners was also too timid to pass a harsh verdict on the mafia: he acquitted 104 of the

picciotti

whose names appeared on the dummy don’s list, on the less than convincing grounds that ‘public rumour’ was the only evidence against them. What this amounted to saying was that everyone in Cirella had seen these men strutting around the square; everyone knew at the very least that they were in cahoots and up to no good. They were visible, in other words. But even under Fascism, visibility alone was not enough to convict.

C

AMPANIA

: The Fascist Vito Genovese

O

N

8 J

ULY

1938

THE

N

EAPOLITAN DAILY

I

L

M

ATTINO

PUBLISHED THE FOLLOWING

short notice.

FASCIST NEWSBOARD

The Fascist Vito Genovese, enlisted in the New York branch of the Fascist Party and currently resident in Naples, has donated 10,000 lire. The Roccarainola branch received 5,000 lire as a contribution to the cost of the land required to build the local party headquarters. The other 5,000 lire is for building Nola’s Heliotherapy Centre.

Vito Genovese would later reportedly subsidise the building of Nola’s Fascist party HQ to the tune of $25,000 (in 1930s values). Visitors to Nola—and there are not many—can still see the building in piazza Giordano Bruno: a white block, long since stripped of its Mussolinian badges, it houses a local branch of the University of Naples, the Faculty of Law in fact.

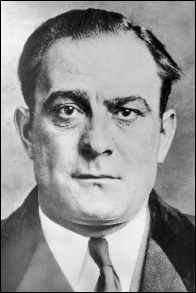

Genovese was born in Risigliano, near Nola, on 21 November 1897. We do not know whether his family had any connections with the Campanian underworld before they emigrated to the United States in 1912. Nonetheless, New York offered bounteous opportunities for violent young immigrants. Vito rose rapidly through the ranks of gangland, alongside his friend, the Sicilian-born Charles ‘Lucky’ Luciano. A now famous mug shot of Genovese from this period shows a bug-eyed enforcer with a skewed crest of black hair.

In 1936, Lucky Luciano received a thirty-to-fifty-year sentence on compulsory prostitution charges. (Which of course he would have avoided had he followed the conventions in force in the mafia’s homeland.) Vito Genovese was scheduled to take over from Luciano at the apex of the New York mafia, an organisation still dominated by Sicilians. But he was also due to face a murder charge, and was afraid that it might result in comparably harsh treatment. So in 1937 he fled to a gilded exile in the land of his birth.

In Italy, Vito Genovese’s generosity, like his Fascism, were self-interested. Strong rumours suggest that he was busy shipping narcotics back to the United States. With the profits, Genovese made his contribution to the Fascist architectural legacy in Campania and lavishly entertained both Mussolini and Count Galeazzo Ciano, the Duce’s son-in-law and Foreign Minister. It is only logical to assume that Genovese had excellent top-level contacts in Nola too.

Evidently, in Campania Fascism lacked the integrity and the attention span needed to follow up on Major Anceschi’s recommendations following his operations in the Mazzoni in 1926–28. One way or another, in Campania Fascism lapsed from the crusading zeal of the Ascension Day speech into a quiet political accommodation with gangsters. As later events would prove, Vito Genovese was now part of a flourishing criminal landscape.

‘The Fascist Vito Genovese’, the New York boss who enjoyed a profitable homecoming in Campania in the 1930s and 1940s.

S

ICILY

: The slimy octopus

W

E HAVE KNOWN FOR A LONG TIME THAT

C

ESARE

M

ORI

’

S BOAST THAT HE HAD BEATEN

the mafia would turn out hollow, and that the Mori Operation was a failure in the long-term. After all, once Fascism fell and democracy was restored, Sicily’s notorious criminal fraternity began a new phase of its history that would prove more arrogant and bloodthirsty than any yet seen. A great deal of energy has been devoted to dishing out responsibility for the mafia’s revival after the Second World War. Conspiracy theorists said it was all the Americans’ fault: the mafia returned with the Allied invasion in 1943. Pessimists put the blame on Italian democracy: without a dictator in charge, the country was just not capable of staging a thoroughgoing repression of organised crime.

Whoever was to blame for the subsequent revival in the mafia’s fortunes, most memories of the campaign to eradicate it were more or less in tune with Fascism’s own trumpet calls. Even some

mafiosi

recalled the alarums of the late 1920s with a shudder. One Man of Honour, despite being too young to remember the Mori Operation, said in 1986 that

The music changed [under Fascism]. Mafiosi had a hard life . . . After the war the mafia hardly existed anymore. The Sicilian Families had all been broken up. The mafia was like a plant they don’t grow anymore.

So, until recently, the historical memory of the Iron Prefect’s titanic campaign of repression in Sicily was fundamentally united: even if the mafia had

not been destroyed, it had at least bowed its head before the thudding might of the Fascist state.

Until recently

. Until 2007, that is, when Italy’s leading historian of the mafia unearthed a startling report that had lain forgotten in the Palermo State Archive. Because of that report—many hundreds of pages long if one includes its 228 appendices—the story of Fascism’s ‘last struggle’ with the mafia must now be completely rewritten. Some of the best young historians in Sicily are busy rewriting it. The Mori Operation, it turns out, involved the most elaborate lie in the history of organised crime.

The report dates from July 1938, and it addresses the state of law and order in Sicily since the last big mafia trial concluded late in 1932. It had no less than forty-eight authors, all of them members of a special combined force of

Carabinieri

and policemen known by the unwieldy title of the Royal General Inspectorate for Public Security for Sicily—the Inspectorate, for short. And the majority of its members were Sicilians, to judge by their surnames.

The report begins as follows.

Despite repeated waves of vigorous measures taken by the police and judiciary [during the Mori Operation], the criminal organisation known in Sicily and elsewhere by the vague name of ‘mafia’ has endured; it has never really ceased to exist. All that happened is that there were a few pauses, creating the impression that everything was calm . . . It was believed—and people who were in bad faith endeavoured to make everyone believe—that the mafia had been totally eradicated. But all of that was nothing more than a cunning and sophisticated manoeuvre designed by the mafia’s many managers—the ones who had succeeded in escaping or remaining above suspicion during the repression. Their main aim was to deceive the authorities and soften up so-called public opinion so that they could operate with ever greater freedom and perversity.

The mafia had sold Fascism an extravagant dummy, the Inspectorate claimed. Some bosses had used the very force and propagandistic éclat of the Mori Operation to make believe that they had gone away. The mafia had its own propaganda agenda—to appear beaten—and its message was broadcast by the Fascist regime’s obliging megaphones. The Palermo

capi

may just as well have ghostwritten Cesare Mori’s

The Last Struggle with the Mafia

.

The story of the 1938 report dates back to 1933, well within a year of the last Mori trial, when there was a crime wave so overwhelming as to make it obvious that the police structures put in place by the Iron Prefect were no longer fit for purpose. The police and

Carabinieri

were reorganised into an

elite force to combat it: the Royal General Inspectorate for Public Security for Sicily. Thus the Fascist state started the struggle with the mafia all over again. Only this time the national and international public that had lapped up reports of the Iron Prefect’s heroics were not allowed to know anything about what was going on.

The men of the Inspectorate picked up again where Mori’s police had left off in 1929. As they did, they slowly assembled proof that the mafia across western Sicily was more organised than anyone except perhaps Chief of Police Ermanno Sangiorgi would ever have dared imagine: the ‘slimy octopus’, they called it.

The chosen starting point was the province of Trapani, at the island’s western tip, where the Mori Operation had made least impact and where criminal disorder was now at its worst: here the mafia ‘reigned with all of its members in place’, the Inspectorate found. When they arrested large numbers of Trapani

mafiosi

, the bosses still at liberty held a provincial meeting to decide on their tactical response. A letter was sent urging everyone in the organisation to keep violence to a minimum until this new wave of repression had crested and broken.

The Inspectorate’s next round of investigations discovered a mafia livestock-smuggling network, 300 strong, that extended across the whole of the west of the island;

mafiosi

referred to it as the

Abigeataria

—something like ‘The Cattle-Rustling Department’. As they always had done, Sicilian

mafiosi

worked together to steal animals in one place and move them to market far away.

Then came the southern province of Agrigento. The Inspectorate’s investigations into an armed attack on a motor coach gradually revealed that the mafia had a formal structure here too.

Mafiosi

interrogated by the Inspectorate used the term ‘Families’ for the structure’s local cells. The Families often coordinated their activities. For example, the men who attacked the motor coach came from three different Families; they had never met one another before their bosses ordered them to participate in the raid, but they nonetheless carried it out in harmony. Even more alarmingly, the Inspectorate discovered that, just as the Mori Operation trials were coming to their conclusion in 1932, bosses in Agrigento received a circular letter from Palermo telling them ‘to close ranks, and get ready for the resumption of large-scale crimes’.

Among the most revealing testimonies gathered by the Inspectorate was that of Dr Melchiorre Allegra, a family doctor, radiographer and lung specialist who ran a clinic in Castelvetrano, in the province of Trapani. Allegra was arrested in the summer of 1937, and dictated a dense twenty-six-page confession that shone the light of the Inspectorate’s policework back into the past. Allegra was initiated in Palermo in 1916 so he could

provide phoney medical certificates for Men of Honour who wanted to avoid serving in the First World War. The

mafiosi

who were formally presented to Dr Allegra as ‘brothers’ included men of all stations, from coach drivers, butchers and fishmongers, right up to Members of Parliament and landed aristocrats. After the Great War, the provincial and Family bosses would often come from across Sicily to meet in the Birreria Italia, a polished café, pastry shop and bar situated at the junction of via Cavour and via Maqueda, in the very centre of Palermo. For a few years, until the Fascist police became suspicious, the Birreria Italia was the centre of the mafia world, a social club for the island’s gangster elite.