Blood Brotherhoods (4 page)

Read Blood Brotherhoods Online

Authors: John Dickie

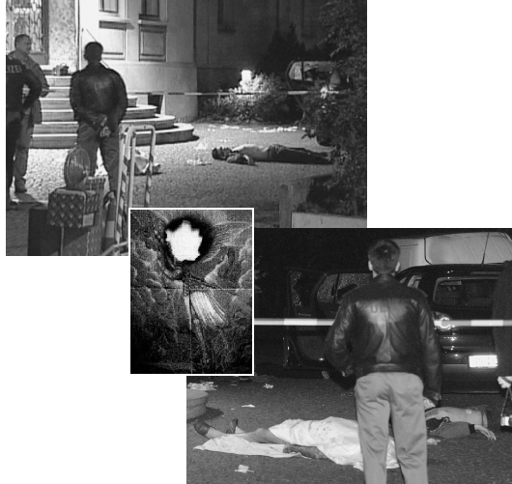

The Duisburg massacre. Europe finally takes notice of the ’ndrangheta, Italy’s richest and most powerful mafia, on 15 August 2007. One of the six victims, Tommaso Venturi, had just celebrated both his eighteenth birthday and his admission into the Honoured Society of Calabria. The partially burned image of the Archangel Michael (inset top), used during the ’ndrangheta initiation ritual, was found in his pocket.

The Duisburg massacre demonstrated with appalling clarity that Italy, and the many parts of the world where there are mafia colonies, still lives

with the consequences of the story to be told here. So before delving into the past it is essential to introduce its protagonists in the present, to sketch three profiles that show succinctly what mafia history is a history of. Because, even after Duisburg, the world is still getting used to the idea that Italy has more than one mafia. There is only a hazy public understanding of how the camorra and the ’ndrangheta, in particular, are organised.

Blood seeps through the pages of mafia history. In all its many meanings, blood can also serve to introduce the obscure world of Italian organised crime today. Blood is perhaps humanity’s oldest and most elemental symbol, and

mafiosi

still exploit its every facet. Blood as violence. Blood as both birth and death. Blood as a sign of manhood and courage. Blood as kinship and family. Each of the three mafias belongs to its own category—its own blood group, as it were—that is distinct but related to the other two in both its organisation and its rituals.

Rituals first: by taking blood oaths, becoming blood brothers, Italian gangsters establish a bond among them, a bond forged in and for violence that is loosened only when life ends. That bond is almost always exclusively between men. Yet the act of marriage—symbolised by the shedding of virginal blood—is also a key ritual in mafia life. For that reason, one of the many recurring themes in this book will be women and how

mafiosi

have learned to manage them.

The magic of ritual is one thing that the ’ndrangheta in particular has understood from the beginning of its history. And ritual often comes into play at the beginning of an

’ndranghetista

’s life, as we know from one of the very few autobiographies written by a member of the Calabria mafia (a multiple murderer) who has turned state’s evidence (after developing a phobia about blood so acute that he could not even face a rare steak).

Antonio Zagari’s career in organised crime started two minutes into January 1, 1954. It began, that is, the very moment he issued from his mother’s womb. He was a firstborn son, so his arrival was greeted with particular joy: his father, Giacomo, grabbed a wartime heavy machine gun and pumped a stream of bullets towards the stars over the gulf of Gioia Tauro. The barrage just gave the midwife time to dab the blood from the baby’s tiny body before he was taken by his father and presented to the members of the clan who were assembled in the house. The baby was gently laid down before them, and a knife and a large key were set near his feebly flailing arms. His destiny would be decided by which he touched first. If it were the key, symbol of confinement, he would become a

sbirro

—a cop, a slave of the law. But if it were the knife, he would live and die by the code of honour.

It was the knife, much to everyone’s approval. (Although, truth be told, a helpful adult finger had nudged the blade under the tiny hand.)

Delighted by his son’s bold career choice, Giacomo Zagari hoisted the baby in the air, parted his tiny buttocks, and spat noisily on his arsehole for luck. He would be christened Antonio. The name came from his grandfather, a brutal criminal who looked approvingly on at the scene from above a walrus moustache turned a graveolent yellow by the cigar that jutted permanently from between his teeth. Baby Antonio was now ‘half in and half out’, as the men of the Honoured Society termed it. He was not yet a full member—he would have to be trained, tested and observed before that happened. But his path towards a more than usually gruesome life of crime had been marked out.

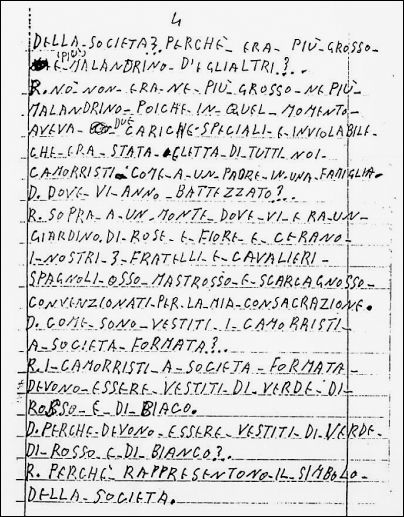

The ‘social rules’. One of many pages of instructions for ’ndrangheta initiation rituals that were found in June 1987 in the hideout of Giuseppe Chilà. Osso, Mastrosso and Carcagnosso, the three Spanish knights who (according to criminal legend) were the founders of the mafia, camorra and ’ndrangheta, are mentioned.

Zagari grew up not in Calabria, but near Varese by Italy’s border with Switzerland, where his father led the local ’ndrangheta cell. As a youth, during his father’s occasional jail stints, Antonio was sent back south to work with his uncles who were citrus fruit dealers in the rich agricultural plain of Gioia Tauro on Calabria’s Tyrrhenian Sea coast. He came to admire his father’s relatives and friends for the respect they commanded locally, and even for the delicacy of their speech. Before uttering a vaguely vulgar word like ‘feet’, ‘toilet’, or ‘underpants’, they would crave forgiveness: ‘Speaking with all due respect . . . ’ ‘Excuse the phrase . . . ’ And when they had no alternative but to utter genuine profanities such as ‘police officer’, ‘magistrate’, or ‘courtroom’, their sentences would topple over themselves with pre-emptive apologies.

I have to say that—for the sake of preserving all those present, and the fine and honoured faces of all our good friends, speaking with all due respect, and excusing the phrase—when the

Carabinieri

[military police] . . .

As the son of a boss, Antonio Zagari’s criminal apprenticeship was a short one. He took a few secret messages into prison, hid a few weapons, and soon, at age seventeen, he was ready to make the passage into full membership.

One day his ‘friends’, as he termed them, copied out a few pages of the Rules and Social Prescriptions he was required to learn by heart before being inducted. It was all, he later recalled, like the catechism children have to memorise before Confirmation and First Communion.

The ‘catechism’ also included lessons in ’ndrangheta history. And having committed the deeds of Osso, Mastrosso and Carcagnosso to memory, Zagari was deemed ready to undergo the most elaborate initiation rite used by any mafia. He was shown into an isolated, darkened room and introduced to the senior members present, who were all arrayed in a circle. For the time being, he had to remain silent, excluded from the group.

‘Are you comfortable my dear comrades?’, the boss began.

‘Very comfortable. On what

?’

‘On the social rules.’

‘Very comfortable

.’

‘Then, in the name of the organised and faithful society, I baptise this place as our ancestors Osso, Mastrosso and Carcagnosso baptised it, who baptised it with iron and chains.’

The boss then passed round the room, relieving each

’ndranghetista

of the tools of his trade, and pronouncing the same formula at each stop.

In the name of our most severe Saint Michael the Archangel, who carried a set of scales in one hand and a sword in the other, I confiscate your weaponry.

The scene was now set, and the Chief Cudgel could intone his preamble to the ceremony proper.

The society is a ball that goes wandering around the world, as cold as ice, as hot as fire, and as fine as silk. Let us swear, handsome comrades, that anyone who betrays the society will pay with five or six dagger thrusts to the chest, as the social rules prescribe. Silver chalice, consecrated host, with words of humility I form the society.

Another ‘thank you’ was sounded, as the

’ndranghetisti

moved closer together and linked arms.

Three times the boss then asked his comrades whether Zagari was ready for acceptance into the Honoured Society. When he had received the same affirmative reply three times, the circle opened, and a space was made for the newcomer immediately to the boss’s right. The boss then took a knife and cut a cross into the initiate’s left thumb so that blood from the wound could drip onto a playing card sized picture of the Archangel Michael. The boss then ripped off the Archangel’s head and burned the rest in a candle flame, symbolising the utter annihilation of all traitors.

Only then could Zagari open his mouth to take the ’ndrangheta oath.

I swear before the organised and faithful society, represented by our honoured and wise boss and by all the members, to carry out all the duties for which I am responsible and all those that are imposed on me—if necessary even with my blood.

The boss then kissed the new member on both cheeks and set out for him the rules of honour. There followed another surreal incantation to wind the ceremony up.

Oh, beautiful humility! You who have covered me in roses and flowers and carried me to the island of Favignana, there to teach me the first steps. Italy, Germany and Sicily once waged a great war. Much blood was shed for the honour of the society. And this blood, gathered in a ball, goes wandering round the world, as cold as ice, as hot as fire, and as fine as silk.

The

’ndranghetisti

could at last take up arms again—in the name of Osso, Mastrosso, Carcagnosso and the Archangel Michael—and resume their day-to-day criminal activity.

These solemn ravings make the ’ndrangheta seem like a version of the Scouts invented by the boys from

The Lord of the Flies

based on a passing encounter with

Monty Python and the Holy Grail

. It would all verge on the comic if the result were not so much death and misery. Yet there is no incompatibility between the creepy fantasy world of ’ndrangheta ritual and the brutal reality of killings and cocaine deals.

Initiation rituals are even more important to the ’ndrangheta than the story of Osso, Mastrosso and Carcagnosso that helps give it an ancient and noble aura. At whatever stage in life they are performed, mafia rites of affiliation are a baptism, to use Antonio Zagari’s word. Like a baptism, such ceremonies dramatise a change in identity; they draw a line in blood between one state of being and another. No wonder, then, that because of the rituals they undergo,

’ndranghetisti

consider themselves a breed apart. A Calabrian

mafioso

’s initiation is a special day indeed.

15 August 2007, in Duisburg, was one such special day. The morning after the massacre, German police searched the victims’ mutilated corpses for clues. They found a partly burned image of the Archangel Michael in the pocket of the eighteen-year-old boy who had just been celebrating his birthday.

The mafia of Sicily, now known as Cosa Nostra, also has its myths and ceremonies. For example, many

mafiosi

hold (or at least held until recently) the deluded belief that their organisation began as a medieval brotherhood of caped avengers called the Beati Paoli. The Sicilian mafia uses an initiation ritual that deploys the symbolism of blood in a similar but simpler fashion to the ’ndrangheta. The same darkened room. The same assembly of members, who typically sit round a table with a gun and a knife at its centre. The aspirant’s ‘godfather’ explains the rules to him and then pricks his trigger finger and sheds a little of his blood on a holy image—usually the Madonna of the Annunciation. The image is burned in the neophyte’s hands as the oath is taken: ‘If I betray Cosa Nostra, may my flesh burn like this holy woman.’ Blood once shed can never be restored. Matter once burned can never be repaired. When one enters the Sicilian mafia, one enters for life.

As well as being a vital part of the internal life of the Calabrian and Sicilian mafias, initiation rites are very important historical evidence. The earliest references to the ’ndrangheta ritual date from the late nineteenth century. The Sicilian mafia’s version is older: the first documentary evidence emerged in 1876. The rituals surface from the documentation again and again thereafter, leaving bloody fingerprints through history, exposing Italian organised crime’s DNA. They also tell us very clearly what happened to

that evidence once it came into the hands of the Italian authorities: it was repeatedly ignored, undervalued and suppressed.