Blood and Thunder (7 page)

Authors: Alexandra J Churchill

Notes

Â

1

The body of Charles William North Garstin was relocated to Cement House Cemetery in the 1950s.

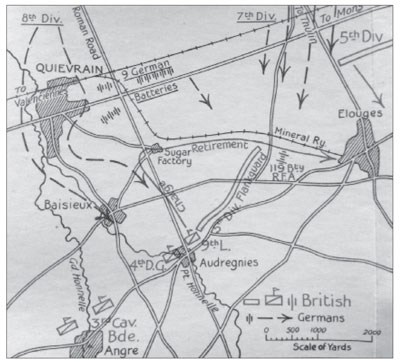

Diagram showing the charge of the 9th Lancers at Audregnies

4

âOur Little Band of Brothers'

As autumn began, large numers of OEs were engaged in a type of conflict that is unfamiliar to many envisioning the Great War. The timeless image of the war is that of the trenches: stagnant warfare, andarmies scrapping over slithers of mud in Flanders and on the Somme. But this was not the war that governments, generals or the troops involved had anticipated. Combatants across Europe were trained to fight on the move and were conducting the opening throes of the conflict as such: seizing positions, defending them briefly and then moving on. It was a fluid, mobile type of warfare similar to the experience of their ancestors on the battlefields of Europe in the nineteenth century.

Nearly one third of the Old Etonians who fell during the Great War have no known grave. Prior to the BEF's descent into Picardy and the environs of the River Aisne in September 1914 only three of the school's casualties were missing and presumed dead, as opposed to actually having a marked burial site. For Eton the retreat changed this, followed by the re-crossing of the river in pursuit of the enemy two weeks later and the Battle of the Aisne. At the time the reaction of the families of these missing men was not one of muted acceptance. The world had not yet seen the opening day of the Somme, or the vile mud of Passchendaele. The idea of young officers having vanished into oblivion in the opening months of the war was shocking, unacceptable even, and the families of some went to extraordinary lengths to obtain answers that they were convinced had to be waiting for them on the battlefields and from the mouths of those that had survived.

As yet, the Guards Regiments had barely fired a shot in anger. When the 4th (Guards) Brigade arrived in France it comprised the 2nd Battalion of the Grenadier Guards, the 1st Irish Guards and both the 2nd and 3rd Coldstream Guards. For many Etonians these regiments were a family tradition. The Coldstream had been formed by General Monck in 1650 and on embarking for the Great War an OE with the same name boarded the transport; whilst another Etonian travelling to France claimed to be a sixth-generation Grenadier. Between them the four Battalions took 125 officers to war and nearly 60 per cent of them had been educated at Eton College. The presence of such high numbers of Etonians in certain units meant that when they were decimated in combat, large numbers of OEs would likely fall together. On 14 September this trend began, twenty of Eton's old boys fell in one day and of them eleven belonged to one of the four Guards regiments.

Amongst their number was a 22-year-old Old Etonian who had barely been with the Grenadiers for a year when war was declared. Mild-mannered, perhaps a little too laid-back and cheerful by nature, John Manners had it all: intellect, looks and athletic ability in just about every sport he tried. His Eton fame had been secured by the Lord's match in 1910. Partly a brainchild of Lord Byron, it had become tradition that the boys of Eton would take on the boys of Harrow School every summer at the Marylebone Cricket Club's famous ground in St John's Wood. At the time it was a social event to rival Ascot or the Grand National and attracted crowds in the tens of thousands.

The match in 1910 ended in a breathtaking manner. Eton was languishing after the first innings, being all out for a pathetic 67. John himself was ninth in the batting order and had been caught out for 4, the future Field Marshal Alexander of Tunis bowling the offending ball. Harrow had been unbeaten all year but the star of the day was Robert Fowler, the Eton captain. Apart from his 64, the second innings was nothing to shout about either. John made 40 not out, the second highest total, and in desperation Boswell KS, the wicket keeper, had racked up 32 as the last man before Harrow went in to bat needing a mere 55 runs to win.

What followed was nothing short of incredible. The Eton captain led a charge that brought the Harrovian batting line up to its knees. Within half an hour Fowler had taken 8 wickets, 5 clean bowled and Harrow were all but obliterated at 32 for 9. Such was their confidence that Harrow's tenth man, Alexander, was stuffing his face with a cream bun when someone burst into a tent at the nursery end and informed him âthat the Harrow wickets were falling like ninepins and that he might be needed at any moment'. He was still trying to swallow his cake in the pavilion and barely had time to get his pads on and to the crease. Alexander managed just 8 runs before the innings was over and Harrow were all out for 45. Eton had won by 9 Fowler became a national celebrity in an instant. Such was the acclaim that one fan letter, simply addressed to âFowler's mother, London' actually found the lady at her hotel.

John Manners had a mischievous sense of humour. He once received a scathing reprimand from Shepherd's Bush Stadium for messing about where he shouldn't have been and went as far as to register his telegraphic address as âBrainfeg, Oxford'. His father was a sportsman too, but was wary of his temperament and had instilled in John the belief that sporting greatness was not enough in itself. He had won the Grand National on his own horse but he hoped that John âunlike himself would be remembered for something more' than his achievements on a playing field or a tennis court.

On the outbreak of war John was most amused when arriving in France that he was not supposed to tell his mother anything at all. âWe are not even allowed to say what country we're in which makes letter writing rather difficult!' he joked. âBut I don't think you would be greatly surprised if you knew.' Disembarking at the end of their voyage had been difficult but he was just thankful that the journey was over. He continued to mock the seriousness of his new adventure. âAll the glamour of war was knocked out of me by that beastly departure from London. Bands oughtn't be allowed to play âAuld Lang Syne'!'

The 2nd Grenadiers first retired across the River Aisne on 31 August just after dawn in sweltering heat. They had marched on for nearly 15 miles, struggling to keep men in the ranks, until reaching the town of Soucy. Major George Darell, or âMa' Jeffreys, had left Eton in 1895. There were âthree pillars' to Ma's loyalty: Eton, the Guards and the Conservative Party. The battalion's second in command, having walked over a hundred miles in a little under a week with his Guardsmen, Ma had had just about enough of wandering through the French countryside with an undetermined number of Germans in pursuit. Sleep that night was curtailed after two hours when shortly after midnight came orders to fall back and take up a position at the edge of the forest of Retz, just to the south. At dawn the guards stopped in the shadow of its dense, towering beech trees, which were draped with a thick mist. In a thin, miserable shower of rain the Grenadier and the Irish Guards drank hot chocolate that tasted faintly of paraffin whilst they looked out on dripping lucerne and damp cornfields. Piles of corn lay about, providing potential cover for the Germans. Here they were to stay until mid afternoon, next to Villers-Cotterêts, waiting for the enemy to arrive and hoping that they could keep from being overrun.

This plan fell apart almost immediately. Rumours arrived of German cavalry approaching, and then little pockets of grey-clad men appeared, running between the piles of wet corn and filtering into the forest on either side of them. The Grenadiers opened fire immediately and the Guards prepared to retire into the forest, falling back on the main road and a junction at a clearing in the trees. Into the undergrowth they slipped, amidst a shower of shells from a German artillery battery. The scene was surreal, looking âfor all the world like ⦠the New Forest on a Spring Day'. In one direction, the enemy fire continued and in the other, deer eyed the khaki intruders. Ma Jeffreys' morning was about to get even more surreal. To his astonishment he was ordered to stand his ground for a few hours in order to give the rest of the nearby troops assembling in and about Villers-Cotterêts time to sit down and eat.

With the Irish Guards, Aubrey Herbert was just as bewildered. âIt was evident if [they] took long ⦠we should be wiped out.' Everyone was on edge. There was an eerie lull and Aubrey, ever the optimist, sat down to write two goodbye letters, including a eulogy to his horse Moonshine. Having done so he wandered off to find the Adjutant, 25-year-old Lord Desmond FitzGerald, another Etonian, to have them posted. âI have the picture in my mind of Desmond constantly sitting in very tidy breeches, writing and calling for sergeants,' Aubrey recalled. âHe never seemed to sleep at all. He was woken all the time and was always cheerful.' On this occasion though Desmond was indignant. âYou seem to think that Adjutants can work miracles,' he snapped at the MP several years his senior. âYou want to post them on the battlefield. It is quite useless to write letters now.' Then he promptly borrowed some of Aubrey's paper and wrote a letter himself, whilst Aubrey passed the time irritating those within earshot with Shakespearean quotes pertaining to cemeteries.

Mid morning arrived. The rising heat combined with the damp to make the atmosphere in the forest stifling and unbearable. At about 11 a.m. there was suddenly an explosion of noise. Ma Jeffreys heard it but couldn't see through the foliage to where the 3rd Coldstream and the Irish Guards had been set upon. The two battalions were over extended, large gaps had opened up between the companies and the Irish Guards were attempting to withdraw slowly down the main road towards Villers-Cotterêts. They could see the Germans coming. As rifle and machine-gun fire fell upon them it was impossible to keep any sense of direction. âWe were together but the wood was so thick that I fear many shot one's own men,' one OE claimed. The terrain was rough. In the half-light there were ferns and brambles waist high, and wide ditches. Aubrey was acting as a galloper, hurtling up and down forest paths carrying information. âIt was like diving on horseback ⦠under ordinary conditions one would have thought it mad to ride at the ridiculous pace we did ⦠but the bullets made everything else irrelevant.' The shower of metal continued to rip through the trees, showering men with leaves and branches. âThe noise was perfectly awful.'

It was impossible to maintain control of the situation. The men of different regiments had become hopelessly confused. Officers took charge of whichever Guardsmen they found. Some orders made it through, others were lost when the men carrying them were cut down. The 3rd Coldstream began to fall back. Hubert Crichton, second in command of the Irish Guards and a veteran of Khartoum and the Boer War, had been at Eton at the same time as Ma Jeffreys in the early 1890s. He had received orders to stay put, but the retirement of their neighbours left him isolated. In the end he fell back too, with German troops just yards from being on top of them.

The brigadier took action. Seizing a company of Grenadier Guards he threw platoons forward, one of them commanded by John Manners. He and his fellow officers charged down a forest path and, taking up the best positions they could, tried to enfilade the Germans. They fought ferociously. Lost amongst the trees they did not receive the order to retire with the rest of the Brigade. Aubrey Herbert watched a man fall to the ground holding a bayonet. Immediately concerned he reined in his horse to see if he could help him but the colonel stopped him. The middle of a chaotic retreat was not the time, he told him. It seemed to the Guards that there was an entire army rolling over them. The Germans were ghostly, flitting out from behind the trees and then back in amongst the greenery.

Shortly after 1 p.m. one of the men coming back to join Aubrey and the colonel claimed that he had seen Hubert Crichton's body lying in the road. Could they be sure? Aubrey was sent forward with directions to investigate. He galloped back through the forest. As he approached the body he realised that it was the man with the bayonet whom he had seen tumble to the ground earlier. A momentary lull had occurred in the firing but the wood was still full of lurking enemy troops. Aubrey jumped from his horse and knelt down. Hubert looked peaceful. Aubrey put his hand on his shoulder and spoke to him for a moment. He leant over his body, mindful of Hubert's wife and two little girls, to check for any letters. Then, hearing German whispers coming from the trees, he fled.

When the Irish Guards finally held a roll call at the end of the regiment's first day of fully fledged battle, the battalion was missing not only its commanding officer, Colonel Morris, and his second in command, Hubert Crichton, but five more officers were unaccounted for, including Aubrey Herbert who was in German hands with a bullet in his side. Ma Jeffreys had assumed command of the Grenadiers and the situation was just as chaotic in both battalions of the Coldstream. The retreat continued, and the following morning the Guards moved on, forced to leave the forest of Retz littered with the bodies of their dead and wounded.

A few days after the clash at Villers-Cotterêts, General Joffre made the landmark decision that would earn him his epitaph as the saviour of France when he decided to make a stand against the German advance. The Battle of the Marne followed. Four complete French armies with the BEF, over a million men, pushed the armies of von Kluck and von Bülow north-east and away from Paris. By 9 September the Allied forces had succeeded in turning the tide of the war. Retreat was inevitable and by 10 September it had become a reality; not a panicked fleeing on the Germans' part; but a sustained retirement nonetheless. The Schlieffen Plan, and with it hopes for a swift, decisive western victory, had failed.