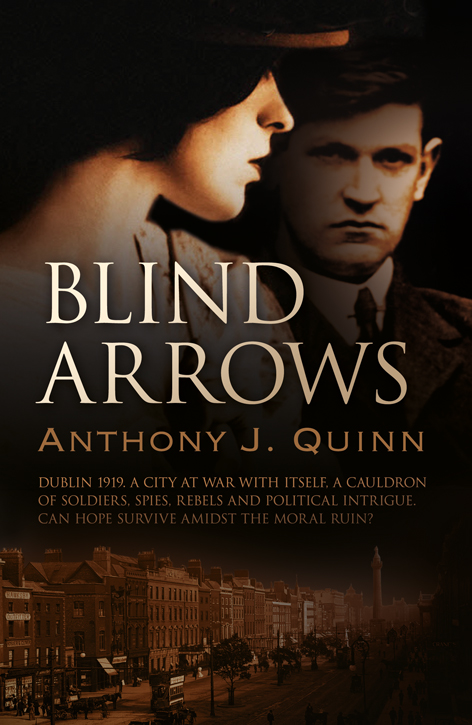

Blind Arrows

Authors: Anthony Quinn

BLIND ARROWS

We are drawn to organise our secrets together, we traitors in this war, our collections of broken vows and betrayals, the undetectable crimes of our guilty hearts...

Dublin 1919. A city at war with itself, a cauldron of soldiers, spies, rebels and political intrigue. The mysterious and seductive Lily Merrin, secretary at Dublin Castle, is on a mission but whose side is she on and what is compelling her to consider the ultimate sacrifice?

Charismatic Irish revolutionary leader, Michael Collins burns with a vision for his country, but others are plotting his downfall.

And now Martin Kant, an English journalist, enters the arena. A serial killer is at large and Lily is in mortal peril. Kant must employ every sinew of his declining resources if he is to rescue not only Lily, but his own soul.

Can hope survive amidst the moral ruin, and love be sustained in a time of soaring ambition and bloodshed?

Anthony J. Quinn

Anthony J. Quinn is an Irish writer and journalist. His debut novel

Â

Disappeared

Â

was shortlisted for a Strand Literary Award by the book critics of the

Â

Guardian, LA Times, Washington Post, San Francisco Chronicle

and other US newspapers. It was also listed by

Kirkus Reviews

as one of the top ten thrillers of 2012. After its UK publication in 2014,

Disappeared

was selected by the

Daily Mail

and the

Times

as one of the best crime novels of the year. His short stories have twice been shortlisted for a Hennessy/New Irish Writing award.

Blind Arrows

Â

is the second in a series of three historical novels set in Ireland during WWI and the War of Independence. He lives in County Tyrone, Northern Ireland.

Praise for

The Blood-Dimmed Tide

âA fascinating reworking of Yeats' genuine fascination with the occult and a historical mystery novel,

The Blood-Dimmed Tide

is the first in a trilogy set in Ireland during this fascinating period of Irish history. If you enjoy this keep an eye out for those that follow'

â

Dublin Duchess

âBringing vividly to life a pivotal point in Ireland's history,

The Blood-Dimmed Tide

is a thrilling mystery story from a unique voice in Irish crime fiction'

â¨

â

Brian McGilloway

âAnthony Quinn blends crime fiction and literature into something truly wondrous and highly entertaining'

â

Ken Bruen

Praise for

Disappeared

âA major piece of work. Eerily tender, a wonderfully wrought classic that is a landmark in the fiction of Northern Ireland⦠Line up the glittering prizes of mystery. This one is going to take 'em all'

â

Ken Bruen

âThis should make Quinn a star'

â

Geoffrey Wansell

, Daily Mail

â⦠outstanding. In the hands of reporter Anthony Quinn, who grew up in Northern Ireland in the 1970s and 80s, the beautifully written

Disappeared

is much more than a routine whodunnit as it unflinchingly lays bare the deep ambivalence that haunts post-peace process Northern Ireland society as it tries to come to terms with its violent past'

â

Irish Independent

â⦠a superb debut steeped in the atmosphere of Northern Ireland'

â

Irish Examiner

âQuinn's knowledge of post-Troubles Northern Ireland effortlessly converts itself into an effective thriller'

â

Publishers Weekly

â⦠a tough yet lyrical novel'

â

The

Sunday Times

âThe Troubles of Northern Ireland are not over. They may no longer reach the headlines, but they continue to damage lives and memories. This is the message so disturbingly, convincingly and elegantly conveyed in Anthony Quinn's first novel,

Disappeared

⦠Beautifully haunting'

â

The

Times

âWell recommended'

â

Euro Crime

For Lucy, Aine, Olivia and Brendan

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I'd like to thank my agent Paul Feldstein for his tireless work, Martin Fletcher, my editor, for his invaluable contributions, and Ion Mills, Claire Watts and Frances Teehan at No Exit Press for doing a wonderful job in bringing this story to life. I'd also like to thank Damian Smyth and the Arts Council of Northern Ireland for their assistance. Finally, I extend my deepest gratitude to my wife Clare, and my children, Lucy, Aine, Olivia and Brendan.

ONE

Dublin, November 1919

Spies and lovers prosper by hiding in other people's secrets

â

the thought occurred to him while sitting in the sunroom of a half-empty hotel overlooking the beachfront at Bray. It was a wintry afternoon, and he had time and space to marshal his thoughts, stationed at the table next to the tall windows, sea spray obscuring the glass, a notebook at hand, and enough tea in a silver pot to keep the waiters at bay until the evening diners arrived.

Ever since starting his clandestine life, he

had taken to visiting the beachfront several afternoons a week. He could feel safely alone here, removed from the war that was unravelling normal life in the heart of Dublin. Naturally, the sense of peace felt more pronounced inside the out-of-season hotel where the efficient bustle of the waiters seemed unconnected to things, to the city and its war, unconnected even to the sunroom and its forlorn backdrop of the sea.

He stirred his cup in the sunlight intensified by the broken, wavering sea, and thought again.

Perhaps we seek out the secret lives of strangers because we have grown tired of insulating our loved ones from the truth, or are spurred on by jealousy, since we understand that the less we know, the more decisively we can love

. He dangled his spoon in the cup and waited for the last thought to call up others, but the cold echo of the sea and the laughter of women and children gesticulating and playing along the promenade sent his thoughts scurrying into darker corners.

He looked up at the terraces of clouds moving across the sky, and waited, motionless, his troubled eyes giving themselves to the distant light. The clouds' sense of purpose and weightlessness made the room seem peaceful again. His mind continued with the train of thought. He composed the words and wrote them in his little leather notebook:

We are drawn to organise our secrets together, we spies in this war, our collections of broken vows and betrayals, the undetectable crimes of our guilty heartsâ¦

A large wave rose and came frowning over the promenade, chasing the figures from the beachfront. He poured himself another cup, and was reaching for the sugar, when the glass door swung open

, and a woman in a wet fur coat entered, disturbing his cocoon of light and peace. The room filled with the rumble of the sea against the promenade. The linen cloths on the discreetly spaced tables rustled and lifted, and a blast of water droplets misted the air, leaving him conscious only of a fleeting translucence that was half sea-light, half skin as the woman's face floated towards him, his heart almost skipping a beat when she stopped at the table next to his. She slipped off her coat, revealing a figure of medium size in a long white dress. He glimpsed her profile: black hair framing a face so clean and delicate it looked as though it might have been found among the empty shells on the beach that morning. Nothing about her, however, struck him as forcibly as her dark eyes, secretly alert, observing him but appearing not to notice him as she composed herself at the table.

After ordering tea, she took out a book, and began to read. At first, he thought she might be waiting for a companion, but as the afternoon progressed,

it became clear she was not expecting anyone. She seemed content to keep sitting with her book, barely changing the page, not raising her head once or glancing in his direction. There was something alluring and mysterious about the way she sat so close to him in the quiet room, the style of her black hair, the pale skin at the nape of her neck. She appeared not to notice his increasing stillness, his desire to discover more about her. When the gaslights came on along the promenade she rose and left without acknowledging his presence in any way.

He always took an interest in solitary female visitors to the hotel, and that evening he made enquiries about her. However, none of the staff knew her name. She did not belong to any of the well-to-do families in Dublin. One of the waiters thought she might work in Dublin Castle, the headquarters for the occupying British forces in Ireland, but beyond that, she was a complete stranger to everyone who worked there.

For the next couple of afternoons she returned to the sun-room, sat at the table next to him, and took out her book, quiet and reserved, avoiding eye-contact in her elegant, white dress, and giving no one cause to notice her, except him. She had captivated his attention completely now, with

her long silences and her determined isolation. He knew that she would mean more to him than the other lonely women he had met: not just another isolated craving that ended abruptly in an anonymous bedroom. She sat so close to his table, he could feel the rhythm of her breathing, the curious calm that made her seem remote from everything else; her enticing presence in the pale afternoon as eerie as a flower that blooms only in mid-winter.

He tried to construct a personality, a life around her, a husband perhaps and children, but her solitary figure was immune to the powers of his imagination. He assumed that knowing the hotel's reputation, she had come to begin an affair, but then he began to think she was unhappy. She must be unhappy, he decided. From her slow movements, her disregard for company, and the way she stared at her book pretending to be engrossed in that same page for hours on end, he guessed that she was suffering from some private sadness.

When she left on the fourth day, he got up and followed her, taking with him his new silver-tipped cane for company. He had pursued women like her before, but never like this, not in the cold daylight of winter in full view of the hotel staffs' inquisitive eyes. For some reason his adventures seemed simpler and more amusing when conducted after the fall of darkness. He trailed her along the sea front and through the public gardens.

He drummed out a tune with his cane on the cobblestones, but she seemed oblivious to it. She floated through the growing shadows of twilight without any sign of fear or caution. Not once did she give in to the temptation to look behind. She was like a serene fugitive from a doomed city, untroubled by the darkness gathering around her. Just as he was about to approach her, she slipped into a restaurant illuminated by orbs of streaming gaslight, and disappeared into a crowd of army officers and their wives. The

military guard posted at the door blocked his way and demanded his papers. He walked away into the night, cleaving the air with his cane in frustration.

They seemed to go together, revolutionary wars and sad, mysterious women. He was aware of their growing presence by the day, walking the streets of Dublin in a semi-trance, taking up tables in restaurants with their detached and martyred airs, staring through the windows of railway carriages, the rain-streaked glass magnifying their sadness, their doomed attachment to fallen men. However, something about the woman in the long white dress struck him as odd and separated her grief from the undifferentiated mass of misery flooding the city.

On the fifth afternoon, he found himself getting angry when she did not turn up at the usual time. He had arrived early, which added to his irritation. He tapped his cane

impatiently against the leg of the table and ignored the waiter's inquiring presence. Then the glass door opened, and in she stepped without acknowledging his presence in any way. His anger abated when he saw that her face had been touchingly done up with make-up and powder. She glanced around the almost empty room as if searching for hints as to what she should do next. Slowly, deliberately, she chose the table next to his, took out her book and focused her attention on a single page.

After a while, rain drifted in from the sea. They looked up together, engrossed by the view from the windows, the deep distances dissolving in water and light, the deserted promenade swept away, the roar of the invisible waves drawing closer. He glanced sideways and saw that her figure had taken on an unreal, watery gleam. She was no longer a stranger but a symbol, another mystery at the heart of things, sitting close to him, lethal and silent, like a gun waiting to be fired. At last, he had found what he had been looking for â a woman with a secret to communicate.

He felt invigorated by the realisation and jumped from his seat. She immediately placed her book on the table, as if to hide what she had been reading, and stared up at him, her eyes filling with alarm. She rose to a half-standing position but sank back when she saw

him swing his cane through the air with deliberate aim.

With a flick of the cane, he knocked the book from her table. Then he bowed courteously and apologised. The look of alarm on her face intensified when he picked up the book and began inspecting the contents. It was a volume of Victorian poetry. A photograph slid from the page she had been reading. His curiosity increased. He

stared at a picture of a child, a boy of about eight or nine, the corners worn away where it had been repeatedly touched, an invitation to sadness deeper than any poem.

He pulled up a seat and made some casual remarks about the afternoon light, the crashing waves, a few deft, indirect observations, giving her time to adjust to his intrusion, settle her emotions. He had no wish to intimidate or upset her. When the waiter appeared, he ordered some tea.

âDo you know who I am?' he asked, pouring her a cup.

She gave a little nod

. Her face was sharply etched in the light of the tall windows.

âYou're wondering what I want of you?'

âI'm almost afraid to ask.'

He sipped from his cup, and put it down next to hers. âThe reason I am here is to draw upon unusual means of support

for my war.'

âAre the hush-hush men following me?'

âI wouldn't know.'

âYou know where I work?'

âYes.

'

She risked a further question. âThen am I in danger?'

âYou misunderstand me. I am here to make you a proposal.'

âWhat sort of proposal?'

He tapped his cane on the photograph. âTell me about the boy

. He bears a striking resemblance to you. Especially around the eyes. Perhaps he's a younger brother?'

She hesitated and stared at the picture, clenching her right hand in her lap.

He spread his hands. âPardon me; you don't have to tell me anything about the boy, if he is

your dear brother or not.'

He was an effective interrogator. She rushed to correct him, explaining her relationship to the boy, without pausing to consider his professional technique, the deliberate mistake accompanied by a humble apology.

âNot my brother; my son.'

He nodded sympathetically, and she continued talking. She told him that her name was Lily Merrin, the daughter of a retired British Major. She had married at eighteen, but her husband had died in the Great War, leaving her to bring up their young son alone. She recounted the catastrophe that had further darkened her young widowhood, robbing her of her beloved son, how she had given up all hope of ever seeing him again.

If she was taken aback by the intensity of the questioning that followed, she did not show it. He made it clear he wanted to hear everything, guiding her through the background details of her life, her upbringing and education, her career and social circle. He

did not show any surprise at her story. He knew about dark places, and the men who lived at the edges of the social order, the kidnappers and blackmailers, the spies and the informers, the saboteurs and the double-crossers.

The light faded from the sea, numbing the mood in the unlit sunroom. Rain began to fall, pecking the glass.

âHaving your son taken away like this is the worst disaster that can befall a mother â like the end of the world.'

âI don't know how I'm meant to deal with it. At least death would have left fewer questions unanswered, less hope and fear in my heart.'

They sat for a while, sipping tea, watching the darkened clouds float in over a wintry sea.

Their vista held little evidence of the dangerous revolution that had overtaken their city, no sense of a country pitching towards its doom, no connection to the ambushes, the bedroom raids, the bombing and shootings, the layered centuries of repression, the paralysis of a nation.

âThe people who have taken away your son are efficient and ruthless,' he said in a controlled voice, not wishing to provoke her grief. âThey are fighting for the heart of this country. It is in their nature to destroy our children, our very name.

You understand how dangerous it will be to have him returned to you?'

She nodded. He paused for thought, arranging her story in his head. He glanced at her face and was pleased to see that he had been shrewd in his choice. There were women he wanted to study from a distance, and there were others he absolutely had to pursue, the ones whose sadness gestured at him in interesting ways, who had a special daring, whose eyes shone with fierce secrets.

After careful consideration, he explained that he felt compelled to help her, but he needed to take certain precautions. Secrets became dangerous when shared with others. He smiled kindly.

âBut, in the circumstances, your desire to be reunited with your son fits in very well with my plans.'

At last, she made

eye contact with him, steady and sustained, a blend of respect and fear.

She swallowed slightly. âWhat is it you want me to do?'