Black Swan Green (5 page)

Authors: David Mitchell

Mrs de Roo’s office smells of Nescafé. She drinks Nescafé Gold Blend non-stop. There’re two ratty sofas, one yolky rug, a dragon’s-egg paperweight, a Fisher-Price toy multi-storey car park and a giant Zulu mask from South Africa. Mrs de Roo was born in South Africa but one day she was told by the government to leave the country in twenty-four hours or she’d be thrown into prison. Not ’cause she’d done anything wrong, but because they do that in South Africa if you don’t agree coloured people should be kept herded off in mud-and-straw huts in big reservations with no schools, no hospitals and no jobs. Julia says the police in South Africa don’t always bother with prisons, and that often they throw you off a tall building and say you tried to escape. Mrs de Roo and her husband (who’s an Indian brain surgeon) escaped to Rhodesia in a jeep but had to leave everything they owned behind. The government took the lot. (The

Malvern Gazetteer

interviewed her, that’s how I know most of this.) South Africa’s summer is our winter so their February is lovely and hot. Mrs de Roo’s still got a slightly funny accent. Her ‘yes’ is a ‘yis’ and her ‘get’ is a ‘git’.

‘So, Jason,’ she began today. ‘How are things?’

Most people only want a ‘Fine, thanks’ when they ask a kid that, but Mrs de Roo actually means it. So I confessed to her about tomorrow’s form assembly. Talking ’bout my stammer’s nearly as embarrassing as stammering itself, but it’s okay with her. Hangman knows he mustn’t mess with Mrs de Roo so he acts like he’s not there. Which is good, ’cause it proves I

can

speak like a normal person, but bad, ’cause how can Mrs de Roo ever defeat Hangman if she never even sees him properly?

Mrs de Roo asked if I’d spoken to Mr Kempsey about excusing me for a few weeks. I already had done, I told her, and this is what he’d said. ‘We must all face our demons one day, Taylor, and for you, that time is nigh.’ Form assemblies’re read by students in alphabetical order. We’ve got to ‘T’ for ‘Taylor’ and as far as Mr Kempsey’s concerned that’s that.

Mrs de Roo made an

I see

noise.

Neither of us said anything for a moment.

‘Any headway with your diary, Jason?’

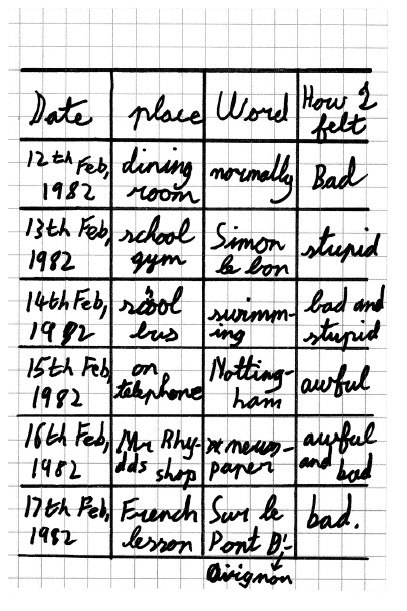

The diary’s a new idea prompted by Dad. Dad phoned Mrs de Roo to say that given my ‘annual tendency to relapse’, he thought extra ‘homework’ was appropriate. So Mrs de Roo suggested that I keep a diary. Just a line or two every day, where I write when, where and what word I stammered on, and how I felt. Week One looks like this:

‘More of a chart, then,’ Mrs de Roo said, ‘than a diary in the classical mode, as such?’ (Actually I wrote it last night. It’s not lies or anything, just truths I made up. If I wrote

every

time I had to dodge Hangman, the diary’d be as thick as the Yellow Pages.) ‘Most informative. Very neatly ruled, too.’ I asked if I should carry on with the diary next week. Mrs de Roo said she thought my father’d be disappointed if I didn’t, so maybe I should.

Then Mrs de Roo got out her Metro Gnome. Metro Gnomes’re upside-down pendulums without the clock part. They tock rhythms. They’re small, which could be why they’re called gnomes. Music students normally use them but speech therapists do too. You read aloud in time with its tocks, like this:

here – comes – the – can – dle – to – take – you – to – bed, – here – comes – the – chop – per – to – chop – off – your – head

. Today we read a stack of N-words from the dictionary, one by one. The Metro Gnome

does

make speaking easy, as easy as singing, but I can hardly carry one around with me, can I? Kids like Ross Wilcox’d say, ‘What’s this, then, Taylor?’, snap off its pendulum in a

nano

second, and say, ‘Shoddy workmanship, that.’

After the Metro Gnome I read aloud from a book Mrs de Roo keeps for me called

Z for Zachariah

.

Z for Zachariah

’s about a girl called Anne who lives in a valley with its own freak weather system that protects it after a nuclear war’s poisoned the rest of the country and killed everyone else off. For all Anne knows she’s the only person alive in the British Isles. As a book it’s utterly brill but a bit bleak. Maybe Mrs de Roo suggested I read this to make me feel luckier than Anne despite my stammer. I got a bit stuck on a couple of words but you’d not’ve noticed if you weren’t looking. I know Mrs de Roo was saying,

See, you

can

read aloud without stammering

. But there’s stuff not even speech therapists understand. Quite often, even in bad spells, Hangman’ll let me say whatever I want, even words beginning with dangerous letters. This (a) gives me hope I’m cured which Hangman can enjoy destroying later and (b) let’s me con other kids into thinking I’m normal while keeping alive and well the fear that my secret’ll be discovered.

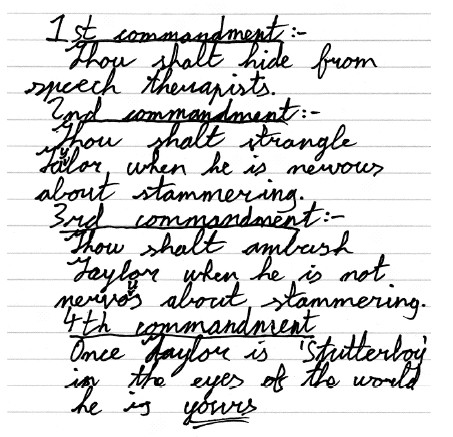

There’s more. I once wrote Hangman’s Four Commandments.

When the session was over, Mrs de Roo asked me if I felt any more confident about my form assembly. She’d’ve liked me to say ‘Sure!’ but only if I meant it. I said, ‘Not a lot, to be honest.’ Then I asked if stammers’re like zits that you grow out of, or if kids with stammers’re more like toys that’re wired wrong at the factory and stay busted all their lives. (You get stammering adults too. There’s one on a BBC1 sitcom called

Open All Hours

on Sunday evenings where Ronnie Barker plays a shopkeeper who stutters so badly, so hilariously, that the audience

pisses

itself laughing. Even knowing about

Open All Hours

makes me shrivel up like a plastic wrapper in a fire.)

‘Yis,’ said Mrs de Roo. ‘That’s the question. My answer is, it depends. Speech therapy is as imperfect a science, Jason, as speaking is a complex one. There are seventy-two muscles involved in the production of human speech. The neural connections my brain is employing now, to say this sentence to you, number in the tens of millions. Little wonder one study put the percentage of people with some kind of speech disorder at twelve per cent. Don’t put your faith in a miracle cure. In the vast majority of cases, progress doesn’t come from trying to kill a speech defect. Try to will it out of existence, it’ll just will itself back stronger. Right? No, it’s a question – and this might sound nutty – of understanding it, of coming to a working accommodation with it, of respecting it, of not fearing it. Yis, it’ll flare up from time to time, but if you know

why

it flares, you’ll know how to douse what makes it flare up. Back in Durban I had a friend who’d once been an alcoholic. One day I asked him how he’d cured himself. My friend said he’d done no such thing. I said, “What do you mean? You haven’t touched a drop in three years!” He said all he’d done was become a teetotal alcoholic. That’s my goal. To help people change from being stammering stammerers into non-stammering stammerers.’

Mrs de Roo’s no fool and all that makes sense.

But it’s sod-all help for 2KM’s form assembly tomorrow morning.

Dinner was steak-and-kidney pie. The steak bits’re okay, but kidney makes me reach for the vomit bucket. I have to try to swallow the kidney bits whole. Smuggling bits into my pocket is too risky since Julia spotted me last time and grassed on me. Dad was telling Mum about a new trainee salesman called Danny Lawlor at the new Greenland superstore in Reading. ‘Fresh from some management course, and he’s Irish as Hurricane Higgins, but my word, that lad hasn’t kissed the Blarney Stone, he’s bitten off chunks of it. Talk about the gift of the gab! Craig Salt dropped by while I was there to instil some God-fearing discipline into the troops, but Danny had him

eating out of his hand

in five minutes flat. Executive material, is that young man. When Craig Salt gives me nationwide sales next year, I’m fast-tracking Danny Lawlor and frankly I don’t care whose nose I put out of joint.’

‘The Irish’ve always had to live by their wits,’ said Mum.

Dad didn’t remember it was Speech Therapy Day till Mum’d mentioned she’d written a ‘plumpish’ cheque for Lorenzo Hussingtree in Malvern Link. Dad asked what Mrs de Roo’d thought about his diary idea. Her comment that it was ‘most informative’ fuelled his good mood. ‘“Informative”? Indispensable, more like! Smart-think Management Principles are applicable across the board. Like I told Danny Lawlor, any operator is only as good as his data. Without data, you’re the

Titanic

, crossing an Atlantic chock full of icebergs without radar. Result? Collision, disaster, goodnight.’

‘Wasn’t radar invented in the Second World War?’ Julia forked a lump of steak. ‘And didn’t the

Titanic

sink before the First?’

‘The principle, o daughter of mine, is a universal constant. If you don’t keep records, you can’t make progress assessments. True for retailers, true for educators, true for the military, true for

any

systems operator. One bright day in your brilliant career at the Old Bailey you’ll learn this the hard way and think, If only I’d listened to my dear wise father. How right he was.’

Julia snorted horsily, which she gets away with ’cause she’s Julia. I can never tell Dad what I really think like that. I can feel the stuff I don’t say rotting inside me like mildewy spuds in a sack. Stammerers can’t win arguments ’cause once you stammer, H-h-hey p-p-presto, you’ve l-l-lost, S-s-st-st-utterboy! If I stammer with Dad, he gets that face he had when he got his Black and Decker Workmate home and found it was minus a crucial packet of screws. Hangman just

loves

that face.

After Julia and I’d done the washing up Mum and Dad sat in front of the telly watching a glittery new quiz show called

Blankety Blank

presented by Terry Wogan. Contestants have to guess a missing word from a sentence and if they guess the same as the panel of celebrities they win crap prizes like a mug tree with mugs.

Up in my room I started my homework on the feudal system for Mrs Coscombe. But then I got sucked in by a poem about a skater on a frozen lake who wants to know what it’s like to be dead so much, he’s persuaded himself that a drowned kid’s talking to him. I typed it out on my Silver Reed Elan 20 Manual Typewriter. I love how it’s got no number 1 so you use the letter ‘l’.

My Silver Reed’s probably what I’d save if our house ever caught fire, now my granddad’s Omega Seamaster’s busted. The worst thing in a locked house in a bad dream, that was.

So anyway, my alarm-radio suddenly said 21:15. I had less than twelve hours. Rain drummed on my window. The rhythms of Metro Gnomes’re in rain and poems too, and breathing, not just tocks of clocks.

Julia’s footsteps crossed my ceiling and went downstairs. She opened the living-room door and asked if she could phone Kate Alfrick about some economics homework. Dad said okay. Our phone’s in the hallway to make it uncomfortable to use, so if I creep over the landing to my surveillance position I can catch just about everything.

‘Yeah, yeah, I

did

get your Valentine’s card, and very sweet it is too, but

listen

, you

know

why I’m calling! Did you pass?’

Pause.

‘Just tell me, Ewan! Did you

pass

?’

Pause. (Who’s Ewan?)

‘

Excellent! Brilliant! Fantastic!

I was going to chuck you if you’d failed, of course. Can’t have a boyfriend who can’t drive.’

(‘Boyfriend’? ‘Chuck’?) Muffled laughter plus pause.

‘No!

No

! He’s

never

!’

Pause.

Julia did the

ohhh!

moany noise she does when she’s mega-jealous. ‘God, why can’t

I

have a filthy-rich uncle who gives me sports cars? Can’t I have one of yours? Go on, you’ve got more than you need…’

Pause.

‘You

bet

. How about Saturday? Oh, you’ve got classes all morning, I keep forgetting…’

Saturday morning classes? This Ewan must be a Worcester Cathedral School kid. Posh.

‘…Russell and Dorrell’s café, then. One thirty. Kate’ll drive me in.’

A sly Julia laugh.

‘No, I certainly will

not

be bringing him.

Thing

spends his Saturdays skulking up trees or hiding down holes.’