Black And Blue (58 page)

Authors: Ian Rankin

‘John?’ the voice said. ‘It’s Brian.’

‘Everything all right?’

‘Fine.’ But Brian’s voice was hollow. ‘I just thought I’d … the thing is … I’m putting in my papers.’ A pause. ‘Isn’t that what they say?’

‘Jesus, Brian …’

‘Thing is, I’ve tried to learn from you, but I’m not sure you were the right choice. A bit too intense maybe, eh? See, whatever it is you’ve got, John, I just don’t have it.’ A longer pause. ‘And I’m not sure I even want it, to be honest.’

‘You don’t have to be like me to be a good copper, Brian. Some would say you should strive to be what I’m not.’

‘Well … I’ve tried both sides of the fence, hell, I’ve even tried sitting

on

the fence. No good, any of it.’

‘I’m sorry, Brian.’

‘Catch you later, eh?’

‘Sure thing, son. Take care.’

He sat down in his chair, stared out of the window. A

bright summer’s afternoon, a good time to go for a walk through the Meadows. Only Rebus had just come back from a walk. Did he really want another? His phone rang again and he let the machine take it. He waited for a message, but all he could hear was static crackle, background hiss. There was someone there; they hadn’t broken the connection. But they weren’t about to leave a message. Rebus placed a hand on the receiver, paused, then lifted it.

‘Hello?’

He heard the other receiver being dropped into its cradle, then the hum of the open line. He stood for a moment, then replaced the receiver and walked into the kitchen, pulled open the cupboard and lifted out the newspapers and cuttings. Dumped the whole lot of them into the bin. Grabbed his jacket and took that walk.

The genesis of this book was a story I heard very early in 1995, and I worked on the book all through that year, finishing a satisfactory draft just before Christmas. Then on Sunday January 29 1996, just as my editor was settling down to read the manuscript, the

Sunday Times

ran a story headlined ‘Bible John “living quietly in Glasgow’”, based on information contained in a book to be published by Main-stream in April. The book was

Power in the Blood

by Donald Simpson. Simpson claimed that he had met a man and befriended him, and that eventually this man had confessed to being Bible John. Simpson also claimed that the man had tried to kill him at one point, and that there was evidence the killer had struck outside Glasgow. Indeed, there remain many unsolved west-coast murders, plus two unsolveds from Dundee in 1979 and 1980 – both victims were found stripped and strangled.

It may be coincidence, of course, but the same day’s

Scotland on Sunday

broke the story that Strathclyde Police had new evidence in the ongoing Bible John investigation. Recent developments in DNA analysis had given them a genetic fingerprint from a trace of semen left on the third victim’s tights, and police had been asking as many of the original suspects as they could find to come forward to have a blood sample taken and analysed. One such suspect, John Irvine McInnes, had committed suicide in 1980, so a member of his family had given a blood sample instead. This seems to have proved a close enough match to warrant exhuming

McInnes’ body so as to carry out further tests. In early February, the body was exhumed (along with that of McInnes’ mother, whose coffin had been placed atop her son’s). For those interested in the case, the long wait began.

As I write (June 1996), the wait is still going on. But the feeling now is that police and their scientists will fail – indeed, already have failed – to find incontrovertible proof. For some, the seed has been sown anyway – John Irvine McInnes will remain the chief suspect in their minds – and it is true that his personal history, compared alongside the psychological profile of Bible John compiled at the time, makes for fascinating reading.

But there is real doubt, too – some of it also based on offender profiling. Would a serial killer simply cease to kill, then wait eleven years to commit suicide? One newspaper posits that Bible John ‘got a fright’ because of the investigation, and this stopped him killing again, but according to at least one expert in the field, this simply fails to fit the recognised pattern. Then there’s the eye-witness, in whom chief investigator Joe Beattie had so much faith. Irvine McInnes took part in an identity parade a matter of days after the third murder. Helen Puttock’s sister failed to pick him out. She had shared a taxi with the killer, had watched her sister dance with him, had spent hours in and out of his company. In 1996, faced with photos of John Irvine McInnes, she says the same thing – the man who killed her sister did not have McInnes’ prominent ears.

There are other questions – would the killer have given his real first name? Would the stories he told the two sisters during the taxi ride be true or false? Would he have gone ahead and killed his third victim, knowing he was leaving a witness behind? There are many out there, including police officers and numbering people like myself, who would refuse to be convinced even by a DNA match. For us, he’s still out there, and – as the Robert Black and Frederick West cases have shown – by no means alone.

Thanks to: Chris Thomson, for permission to quote from one of his songs; Dr Jonathan Wills for his views on Shetland life and the oil industry; Don and Susan Nichol, for serendipitous help with the research; the Energy Division of the Scottish Office Industry Department; Keith Webster, Senior Public Affairs Officer, Conoco UK; Richard Grant, Senior Public Affairs Officer, BP Exploration; Andy Mitchell, Public Affairs Advisor, Amerada Hess; Mobil North Sea; Bill Kirton, for his offshore safety expertise; Andrew O’Hagan, author of

The Missing

; Jerry Sykes, who found the book for me; Mike Ripley, for the video material; the inebriated oil-worker Lindsey Davis and I met on a train south of Aberdeen; Colin Baxter, Trading Standards Officer

extraordinaire

; my researchers Linda and Iain; staff of the Caledonian Thistle Hotel, Aberdeen; Grampian Regional Council; Ronnie Mackintosh; Ian Docherty; Patrick Stoddart; and Eva Schegulla for the e-mail. Grateful thanks as ever to the staffs of the National Library of Scotland (especially the South Reading Room) and Edinburgh Central Library. I’d also like to thank the many friends and authors who got in touch when the Bible John case hit the headlines again early in 1996, either to commiserate or to offer suggestions for tweaks to the plot. My editor, Caroline Oakley, had faith throughout, and referred me to the James Ellroy quote at the start of my own book … Finally, a special thank you to Lorna Hepburn, who told me a story in the first place …

Any ‘implags’ will be from the following:

Fool’s Gold

by Christopher Harvie;

A Place in the Sun

by Jonathan Wills;

Innocent Passage: The Wreck of the Tanker

Braer by Jonathan Wills and Karen Warner;

Blood on the Thistle

by Douglas Skelton;

Bible John: Search for a Sadist

by Patrick Stoddart;

The Missing

by Andrew O’Hagan.

Major Weir’s quote – ‘creatures tamed by cruelty’ – is actually the title of Ron Butlin’s first poetry collection.

© Rankin

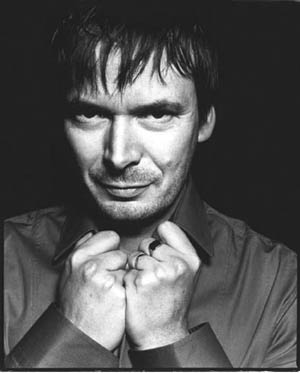

© RankinABOUT IAN RANKIN

Ian Rankin, OBE, writes a huge proportion of all the crime novels sold in the UK and has won numerous prizes, including in 2005 the Crime Writers’ Association Diamond Dagger. His work is available in over 30 languages, home sales of his books exceed one million copies a year, and several of the novels based around the character of Detective Inspector Rebus – his name meaning ‘enigmatic puzzle’ – have been successfully transferred to television.

Introduction to DI John Rebus

Introduction to DI John RebusThe first novels to feature Rebus, a flawed but resolutely humane detective, were not an overnight sensation, and success took time to arrive. But the wait became a period that allowed Ian Rankin to come of age as a writer, and to develop Rebus into a thoroughly believable, flesh-and-blood character straddling both industrial and post-industrial Scotland; a gritty yet perceptive man coping with his own demons. As Rebus struggled to keep his relationship with daughter Sammy alive following his divorce, and to cope with the imprisonment of brother Michael, while all the time trying to strike a blow for morality against a fearsome array of sinners (some justified and some not), readers began to respond in their droves. Fans admired Ian Rankin’s re-creation of a picture-postcard Edinburgh with a vicious tooth-and-claw underbelly just a heartbeat away, his believable but at the same time complex plots and, best of all, Rebus as a conflicted man trying always to solve the unsolvable, and to do the right thing.

As the series progressed, Ian Rankin refused to shy away from contentious issues such as corruption in high places, paedophilia and illegal

immigration, combining his unique seal of tight plotting with a bleak realism, leavened with brooding humour.

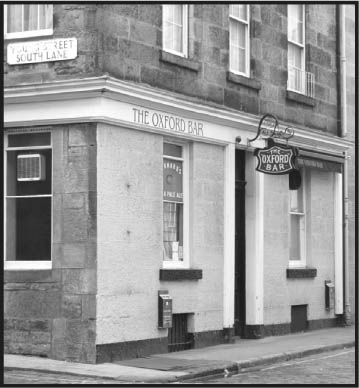

In Rebus the reader is presented with a rich and constantly evolving portrait of a complex and troubled man, irrevocably tinged with the sense of being an outsider and, potentially, unable to escape being a ‘justified sinner’ himself. Rebus’s life is intricately related to his Scottish environs too, enriched by Ian Rankin’s attentive depiction of locations, and careful regard to Rebus’s favourite music, watering holes and books, as well as his often fraught relationships with colleagues and family. And so, alongside Rebus, the reader is taken on an often painful, sometimes hellish journey to the depths of human nature, always rooted in the minutiae of a very recognisable Scottish life.