Bittersweet (9 page)

Authors: Peter Macinnis

A yellow fever epidemic on Barbados around 1647 killed an estimated 6000 whites, many of them indentured servants. This increased the demand for black slaves in the 1650s, but for the moment the wars in Britain kept up the supply of indentured servants. As the number of black slaves increased, cheap white labour was needed to keep control. An Act of 1652 provided a solution, allowing two justices of the peace to

. . . from tyme to tyme by warrant . . . cause to be apprehended, seized on and detained all and every person or persons that shall be found begging and vagrant . . . to be conveyed into the port of London, or unto any other port . . . from which such person or persons may be shipped . . . into any forraign collonie or plantation . . .

In other words, the magistrates, who represented the wealthy of a borough or parish, could ensure that the poor, who otherwise would be a cost to the parish, were rapidly and permanently removed. Note the use here of âplantation' as a synonym for âcolony'. Up until about 1650 it was people who were thought of as planted, and settlements of English families in Wales or Scotland were also âplantations'. It was only later that plantation came to mean a single (generally monocultural) farm. When first settled, Barbados was a plantation of people; it became a sugar plantation when sugar cane was introduced, and then a sugar colony filled with sugar plantations.

THE WHITE SLAVES

The indentured servants who survived the yellow fever probably saw themselves as fortunate, especially those who had gone to the

For

the most part, the plantations of Barbados were clustered near the coast.

islands of their own accord and were able to hire themselves out. The servants who had been âBarbadoed' by a court on a trumped-up charge, or stolen away from their families by the Spirits and sold into virtual slavery in the islands, might have accounted themselves fortunate to get out of plague-ridden London, but many died of island diseases instead. For some this would have been a happy release. It was the island diseases that kept servants in short supply, so that judges in England and Ireland would happily find prisoners guilty and send them to the West Indies, or âBarbadoe' them, as the saying went. It was why the Spirits were able to operate in the various ports; because there was such a shortage of servants they could pay well for people to turn a blind eye, knowing they would be well paid for all they captured.

The Spirits got up to all sorts of tricks, the same ones the crimps of that time played on sailors, using knock-out potions or getting people drunk, and sending the victims to sea with forged papers showing they were indentured. This meant the victim would spend seven years working for a master who generally cared little for the welfare of a servant who would be lost to him at the end of that time.

Of course, not all the servants could get away from their indentures. Under a code passed in 1661, setting out the rights of master and servant, the servants, just like slaves, were forbidden to engage in commerce, and any of a large number of petty offences could lead to a year being added to the period of servitude. Passes were required for servants to be off their master's property, and the dishonest master had plenty of opportunities to goad servants into punishable actions so their periods of servitude could be extended.

Being indentured was so bad that when Generals Penn and Venables were in Barbados in 1654 to outfit for their attack on Hispaniola and Jamaica, many servants ran away to the shipsâ while those on the ships, knowing what life at sea was like, fled ashore. In the end, Cromwell's great Western Design to undo Catholic Spain meant 2000 servants from Barbados perished on Jamaica, so in February 1656 Cromwell sent troops into London to find 1200 women of âloose life' and send them to Barbados. Within days another 400 were sent off.

The planters always complained about the servants. Even though Scotland was under the same king, it was still a different country, and the planters asked in 1667 to be allowed free trade in servants with Scotland, and to transport 1000 to 2000 English servants to the colony. Still nobody wanted the Irish, because it was believed that, being Roman Catholic, they were likely to help the French or the Spanish if they could. The proportion of servants to slaves was a bigger worry, however, so the planters still took what servants they could get.

By 1680 there were only 3000 indentured servants on Barbados, down from 13 000 in the 1650s. By that time there were so many slaves that the masters used all sorts of legal tricks to hold their indentured servants, but those who were out of indenture could pick and choose where and how they worked.

When the Monmouth rebellion broke out in 1685, the planters got a break. The bastard Duke of Monmouth tried to seize the British throne but failed, and his followers were either put to death or, more often, Barbadoed. The Spirits had a fine old time, snatching extra bodies and sending them off with papers showing their victims as convicted rebels.

Most of the former servants had skills that were badly needed, and they could set their own price. Many of the advances in sugar preparation (like the Jamaica Train discussed in Chapter 6) must have come from servants who had reached sugar master status. They had got their training thanks to the Spanish Inquisition and the way the inquisitors had treated the Portuguese Jews, who had been happy and safe in Portugal until a few years before the Great Armada, when Spain took over Portugal and the Inquisition moved in on the Jews.

Most of the Jews in Portugal had fled Spain and its Inquisition a generation or two earlier, and now they shifted again, to Holland, where they were welcomed for their skills. Some of them moved to South America when the Dutch took over Per-nambuco in the north of Brazil. The Jews, seen as an under-class, managed the daily operations of the plantations, and more importantly, the mills. When the Dutch were forced out of Pernambuco, many of the Jews went with them to Amsterdam, but others went to Barbados, where they provided the skills base that the English sugar planters desperately needed.

THE ROYALIST REFUGEE

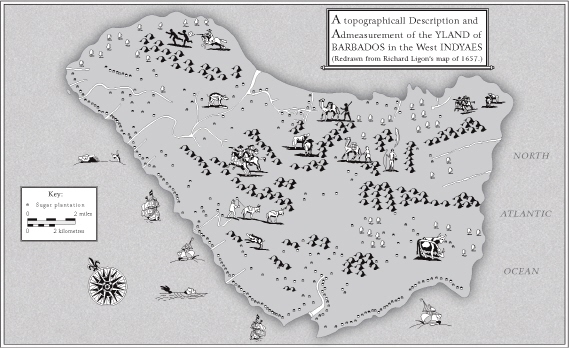

During the turmoil of the English Civil War of the 1640s, the royalist Richard Ligon felt it would be safer to be out of England than to stay there. So he took himself off to the peace and calm of the plantation of Barbados in 1647, not returning home until 1650, by which time life in England was a little more stable.

He spent a pleasant enough three years, learning the art of sugar making among other things, and set down what he saw in

A True & Exact History of the Island of Barbados

. Because he was there long enough to observe closely, but not long enough to become part of the community, Ligon's account gives us the truth, hopefully unvarnished by any desire to censor the facts. For example, he explains that:

The slaves and their posterity, being subject to their Masters for ever, are preserv'd and kept with greater care than the servants, who are theirs but for five years, according to the law of the island. So that for the time, the servants have the worser lives, for they are put to very hard labour, ill lodging, and their dyet very slight. Most of them are Irish and a sullen bunch, but that may be on account of the treatment meted out to them, I know not. The usage of the Servants, is much as the Master is, merciful or cruel. Those that are merciful, treat their Servants well, but if the Masters be cruel, the Servants have very wearisome lives.

Before his time in the island, he tells us,

. . . the first people in Barbados, made tryal first of tobacco, cotton, indigo, and only then turned to sugar canes. The planters made tryal of them and finding them to grow, they planted more and more, as they grew and multiplyed on the place, till they had such a considerable number, as they were worth the while to set up a very small

Ingenio

, as we call the place where crushing and boiling down to make the sugar takes place.

At the

Ingenio

, he reports, the cut cane is placed on a platform called a

Barbycu

, a raised stand with a double rail to stop the cane falling out, about 9 metres long and 3 metres wide (in spite of the size, this was a close relation to our modern barbecue).

Then there is a set of three rollers, with perhaps five horses or oxen driving the middle roller, âwhich is cog'd to the other two, at both ends':

A

Negre

puts in the canes of one side, and the rollers draw them through to the other side, where another

Negre

stands and receives them and returns them back on the other side of the middle roller which draws the other way. So that having past twice through, that is forth and back, it is conceived that all the juice is prest out; yet the Spaniards have a press, after both the former grindings, to press out the remainder of the liquor . . .

But that, he explains in a bluff patriotic manner, is because the Spaniards' cane is poorer. The crushed cane is set aside, some six-score paces away, and the juice:

. . . runs under ground in a Pipe or gutter of lead, cover'd over close, which pipe or gutter, carries it into the Cistern, which is fixt neer the staires, as you go down from the Mill-house to the boyling house. But it must not remain in the Cisterne above one day, lest it grow sowr; from thence it is to passe through a gutter, (fixt to the wall) to the Clarifying Copper . . . As the skumme rises, it is conveyed away, as also the skumme from the second Copper, both which skimmings, are not esteem'd worth the labour of stilling; because the skum is dirtie and gross: But the skimmings of the other three Coppers, are conveyed down to the Still-house, there to remain in the Cisterns, till it be a little sowr, for till then it will not come over the helme and make good rum.

. . . there is thrown into the four last Coppers, a liquor made of water and ashes which they call Temper, without which, the Sugar would continue a clammy substance and never kerne. Once the sugar master has determined that the sugar in the last copper is ready, two teaspoonfuls of Sallet Oyle [salad oil], such as we put on raw vegetables to make a sallet, are added and then the syrup is ladled out. Above all, it is important to throw in some cold water, in order that the last of the syrup should not burn, for the copper is fixed in place over an open fire, and as soon as the copper is empty, syrup from the penultimate copper must be added.

. . . And so the work goes on, from Munday morning at one a clock, till Saturday night, (at which time the fires in the Furnaces are put out) all houres of the day and night, with fresh supplies of men, Horses and Cattle. The liquor being come to such a coolness, as it is fit to be put in the Pots, they bring them neer the Cooler, and stopping first the sharp end of the Pot (which is the bottom) with Plantine leaves, (and the passage there no bigger than a man's finger will go in at) they fill the Pot and set it between the stantions in the filling room, where it staies till it be thorough cold, which will be in two days and two nights; and then if the Sugar be good, to be removed into the Cureing house, but first the stopples are to be pulled out of the bottom of the pots, that the Molosses may vent itself at that hole.

. . . The Molosses, in a well-run Ingenio, is converted into Peneles, a kind of Sugar somewhat inferiour to the Muscovado. . . . And this is the whole process of making the Muscovado Sugar, whereof some is better, and some worse, as the Canes are; for, ill Canes can never make good Sugar.

I call those ill, that are gathered either before or after the time of such ripeness, or are eaten by Rats and so consequently rotten, or pulled down by the vines men call Withes, or lodged by foule weather and ill winds, either or which, will serve to spoil such Sugar as is made of them.

A major improvement in the lot of the planters came when rum became part of the sugar industry. It made marginal operations profitable, loss-making plantations became profitable, and planters still losing money found a new comfort. Almost nothing was too poor to go into the fermentation vats, other than the first couple of skimmings from the coppers. Richard Ligon is once again one of our best witnesses:

After it has remained in the Cisterns . . . till it be a little soure, (for till then, the Spirits will not rise in the Still) the first Spirit that comes off, is a small Liquor, which we call low-wines, which Liquor we put into the Still, and draw it off again; and of that comes so strong a Spirit, as a candle being brought to a near distance, to the bung of a Hogshead or But, where it is kept, the Spirits will flie to it, and . . . set all afire.

This volatility of the rum made it quite risky, and Ligon describes how they âlost an excellent Negro' to a rum explosion when a candle was used for illumination while a jar of spirit was being added to a butt of rum:

. . . the Spirit being stirr'd by that motion, flew out, and got hold of the flame of the Candle, and so set all on fire and burnt the poor Negro to death, who was an excellent servant. And if he had in the instant of firing, clapt his hand on the bung, all had been saved; but he that knew not that cure, lost the whole vessel of Spirits, and his life to boot . . .