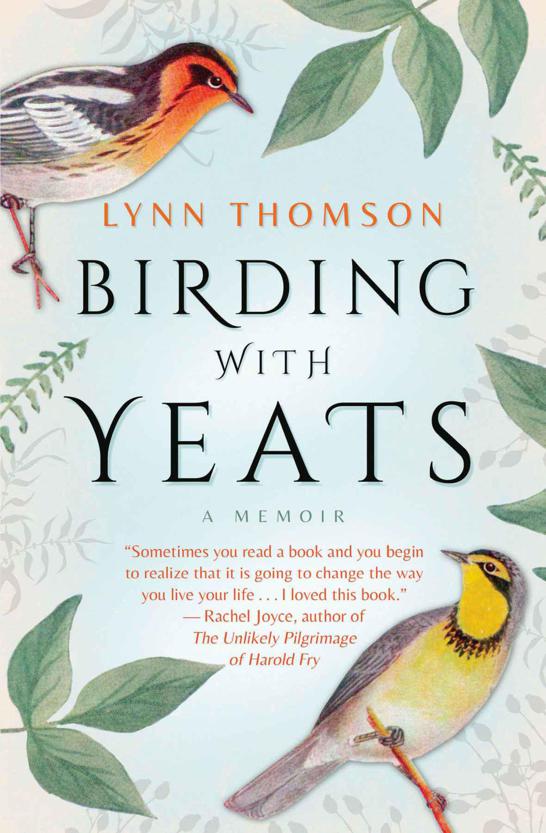

Birding with Yeats: A Mother's Memoir

Read Birding with Yeats: A Mother's Memoir Online

Authors: Lynn Thomson

Copyright ©

2014

Lynn Thomson

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

Distribution of this electronic edition via the Internet or any other means without the permission of the publisher is illegal. Please do not participate in electronic piracy of copyrighted material; purchase only authorized electronic editions. We appreciate your support of the author’s rights.

This edition published in

2014

by

House of Anansi Press Inc.

110

Spadina Avenue, Suite

801

Toronto, ON, M

5

V

2

K

4

Tel.

416

-

363

-

4343

Fax

416

-

3

63

-

1017

www.houseofanansi.com

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication

Thomson, Lynn,

1960

–, author

Birding with Yeats: a memoir / Lynn Thomson.

Issued in print and electronic formats.

ISBN

978

-

1

-

77089

-

389

-

4

(pbk.).—ISBN

978

-

1

-

77089

-

390

-

0

(epub)

1

. Thomson, Lynn,

1960

–.

2

. Thomson, Lynn,

1960

– —Family.

3

. Mothers and sons.

4

. Birdwatching. I. Title.

HQ

799

.

15

.T

46

2014

649

’.

125

C

2013

-

90

6999

-

2

C

2013

-

907000

-

1

Library of Congress Control Number:

2013918882

Jacket design: Alysia Shewchuk

Photo of Lynn and Yeats Thomson courtesy of Barbara Stoneham.

Maps by Alysia Shewchuk.

We acknowledge for their financial support of our publishing program the Canada Council for the Arts, the Ontario Arts Council, and the Government of Canada through the Canada Book Fund.

For Ben and Yeats

Around me the trees stir in their leaves

and call out, “Stay awhile.”

The light flows from their branches.

And they call again, “It’s simple,” they say,

“and you too have come

into the world to do this, to go easy, to be filled

with light, and to shine.”

Mary Oliver, from “When I Am Among the Trees”

PROLOGUE

PROLOGUE

IF I SIT IN

a forest thick with pines and pay close attention to the sound of every living thing, I feel as though my heart might split open. I put my ear to a clump of moss and hear the Earth breathe. There are a billion little creatures chewing in the leaf mould, a billion tiny wings whirring under the blackberry thicket. When I lie down in the tall grass, I hear this and I’m slowly consumed by the press of nature.

I come out of the forest on top of a hill and into a meadow of sumac and juniper. The smell is different here; the heat feels different. These small trees give off such a different vibration from those tall pines. In a pine forest in the wind, all the sound is high up in the treetops, whooshing and sighing. Ferns on the forest floor, green and straining towards the light, give off their own slightly bitter aroma.

If I left this place for the tropics, with all those dripping, viney trees, would I long eternally for the pines? Would I lie in bed at night listening to the howler monkeys scream and feel the longing spin through every cell of my body? Would I fall asleep with the smell of frangipani enveloping me and wake with the scent of pine on my skin?

And I haven’t even mentioned the birds! The chickadees alone, with their incessant

deedeedee

, can rattle my senses, not to mention the nuthatches and the

downy woodpecker

peck-peck-pecking

at the trees.

I find that when I really pay attention, I’ll remember which bird I’m hearing (sounds almost like a robin, must be a red-eyed vireo), which bird that is with the black-and-yellow head (

Blackburnian warbler

), and which tiny bird is scratching away under the forsythia (

house wren

). But if my attention is caught up in other things, the bird names don’t come as easily. On a depressingly regular basis I’ll say to my husband, Ben, “What kind of bird is that?” and he’ll say, “That’s a squirrel.” At the cottage we have red squirrels that can sound like demented

blue jays

, but I should be able to recognize our city squirrels. It’s a good reminder to stay present, instead of allowing my mind to wander and daydream.

Part of the reason my son, Yeats, and I go anywhere is to bird-watch. It has become a habit. We rarely set out on an expedition with the intention of seeing one particular bird species. We just go birdwatching. The act of being outdoors looking for birds, especially ones we’ve never seen before, is enough. Some people are very competitive in their birding. Maybe they’ll die happy, having seen a thousand species before they die, but I’ll die happy knowing I’ve spent all that quiet time being present.

Sometimes I think that the point of birdwatching is not the actual seeing of the birds, but the cultivation of patience. Of course, each time we set out, there’s a certain amount of expectation that we’ll see something, maybe even a species we’ve never seen before, and that it will fill us with light. But even if we don’t see anything remarkable — and sometimes that happens — we come home filled with light anyway.

Birding complements Yeats’s personality — his patience, his calmness, his drive to make lists, and his fabulous memory. It also complements his desire to be in the natural world, to see beautiful things, and to seek deeper meaning about our place as a species on this earth.

I think the most important quality in a birdwatcher is a willingness to stand quietly and see what comes. Our everyday lives obscure a truth about existence — that at the heart of everything there lies a stillness and a light.