Bill O'Reilly's Legends and Lies (41 page)

Read Bill O'Reilly's Legends and Lies Online

Authors: David Fisher

Billy the Kid was locked up in the prison in Santa Fe to await trial. During that time, he wrote several letters to Governor Wallace, pleading for the governor to intercede. “I expect you have forgotten what you promised me, this month two years ago, but I have not and I think you ought to have come and seen me…. I have done everything that I promised you I would and you have done nothing that you promised me.” The governor did not respond.

While pleading for a pardon, Billy and his men planned an escape and began to dig

their way out of the prison. When this tunnel was discovered, the Kid was put in solitary confinement, chained to the floor of his cell.

In April, he was taken to Mesilla, a town to the south of Santa Fe, and tried for the murders of Buckshot Roberts and Sheriff William Brady. He was acquitted of the Roberts killing on a technicality, his attorney arguing successfully that Roberts was not shot on federal property, and therefore the federal court had no jurisdiction. However, Billy was not as fortunate in his second trial. After hearing one day of testimony, Judge Warren Bristol pronounced him guilty, then sentenced him to “hang, until you are dead, dead, dead.”

It is said that the Kid responded by telling the judge, “You can go to hell, hell, hell.”

Billy the Kid was the only man convicted of a crime committed during the Lincoln County War, which he believed to be patently unfair. His only hope, he understood, was that the governor would honor the agreement they had made. As he told a reporter, “I think he [Wallace] ought to pardon me…. Think it hard that I should be the only one to suffer the extreme penalties of the law.” On April 16, he was taken by wagon to Lincoln, where he was scheduled to be hanged on May 13, between the hours of nine a.m. and three p.m. Among the seven men who guarded him during that five-day trip was an old enemy, Bob Olinger, who had fought for Dolan in the war and, from all accounts, was especially hard on the Kid. It was reported that more than once he poked him with his shotgun and dared him to try to escape so that he could shoot him in the back, “Just like you did Brady.”

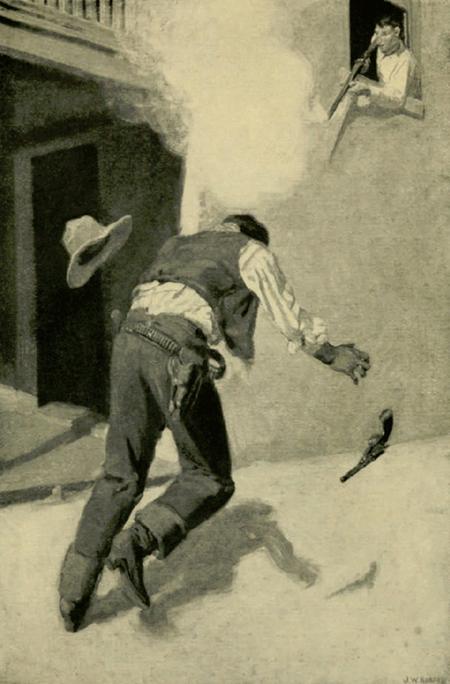

In Lincoln, the Kid was shackled to the floor on the second story of a merchant building, guarded by Olinger and deputy James W. Bell. On the evening of April 28, Olinger went across the street to get some dinner, leaving the Kid alone with Deputy Bell. People have always said Bell was a decent man who was just in the wrong place at the wrong time. There are several versions of what happened next, but they all usually begin with Billy asking the deputy to take him outside to the privy. Perhaps Billy shoved Deputy Bell down the steps, then hobbled into the gun room and grabbed a pistol. Maybe he bludgeoned Deputy Bell with his chains and grabbed his gun. Or perhaps Billy never touched Deputy Bell but instead retrieved a pistol that had been planted for him in the latrine. However it happened, Billy the Kid added to his legend by obtaining a gun and shooting Deputy Bell, who staggered into the street and died. Then, still in chains, Billy managed to get into the armory and grab Olinger’s double-barreled shotgun, the very gun with which he had been poked and taunted. He then stood at the window, patiently awaiting the return of Robert Olinger.

It was not a long wait. Hearing the shots, Olinger raced from the hotel dining room. A passerby warned him, “Bob, the Kid has killed Bell.” And, at that moment, Olinger saw the

Kid framed in the window only a few feet away, holding a shotgun. “Hello, Bob,” Billy is reputed to have said.

Billy the Kid escapes from prison by killing deputy Robert Olinger.

Olinger accepted his fate and has been quoted as saying, “Yes, and he’s killed me, too.”

Billy the Kid fired both barrels; Olinger died without another word. With the help of people who were never identified, he was able to sever his chains, arm himself, and then steal a horse and ride out of town.

Pat Garrett had been in White Oaks when the daring escape took place. He assumed that Billy would head immediately for the Mexican border. So he bided his time, waiting until the following July, when he heard that Billy the Kid might be visiting a lady friend out at Pete Maxwell’s place. He rode out there that night with his two deputies. Not surprising, there are other versions of the final confrontation between Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid. In one, Garrett tied up and gagged Paulita Maxwell, and when the Kid came in to see her, Garrett let loose with both barrels of his shotgun. There is no argument, though, that Pat Garrett shot and killed a man at Pete Maxwell’s ranch on the night of July 14. The man believed to be Billy the Kid was buried by his Mexican friends on the Maxwell Ranch. A white wooden cross marked his grave, and inscribed on it were the words

DUERME BIEN, QUERIDO

(“Sleep well, beloved”).

Almost immediately, souvenir hunters started pulling at the grave site, so within days, his body was moved to the nearby Fort Sumner military cemetery and buried next to his friends Tom O’Folliard and Charlie Bowdre. The inscription on their stone reads simply,

PALS,

then identifies the three men.

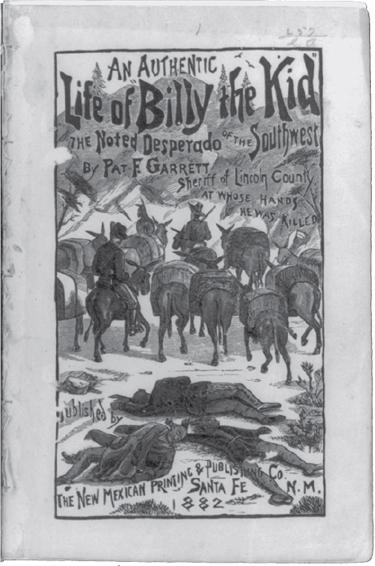

Pat Garrett did not receive the attention he had hoped for, and in fact, many people believed he had shot the Kid in the back in a cowardly manner. At an inquest, Garrett stated, “He came there armed with a pistol and a knife expressly to kill me if he could. I had no alternative but to kill him or suffer death at his hands.” The coroner’s jury ruled it a justifiable homicide. To profit from his success in tracking down the outlaw Billy the Kid, Garrett published a ghostwritten book in 1882 entitled

The Authentic Life of Billy, the Kid.

It was moderately successful but served primarily to embellish the growing legend of William H. Bonney. When Garrett ran for sheriff in the next election, he was defeated. In 1884, he ran for the New Mexico state senate, was also defeated, and left New Mexico for Texas. In 1908, he was shot to death outside Las Cruces, New Mexico, allegedly during an argument about goats grazing on his land without permission. His body was found lying by the side of the road.

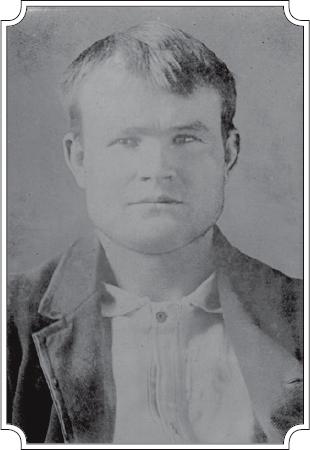

In his twenty-one years, Billy the Kid was credited with killing twenty-one men, but as with so much else about his life, that number certainly is exaggerated. It is known that he killed at least four men himself and was involved in five more fatal shootings. That’s nine. As for the others, no one will ever know how many notches were on his gun.

Months after he had shot Billy the Kid, Pat Garrett published this ghostwritten book, which did more to support the growing legend of Billy the Kid than benefit the sheriff.

And as with other notorious outlaws, the story doesn’t end in that hacienda. Legends take on a life of their own, and people wanted to believe that the Kid who’d pulled off so many daring feats and escapes had executed just one more. Rumors quickly surfaced that Billy the Kid did not die that night. To support these claims, people have pointed out that no photographs of the body exist, no death certificate was ever issued, Pat Garrett was never paid the reward, and the three coroner’s jury reports contained conflicting testimony and were signed by people who admitted they did not witness the shooting. In fact, beyond Pat Garrett’s claims, there is little evidence that the victim was Billy the Kid.

Although only twenty-one years old when he died, Billy the Kid had shot his way into American history. His legend has been celebrated in dime novels, books, comics, plays, songs, poems, and even an Aaron Copeland ballet. He has been portrayed more often in film and television than any other person, by actors including Paul Newman, Kris Kristofferson, and Marlon Brando.

Is it possible that Billy the Kid actually survived that night? According to one version, he was badly wounded, but the Mexican women of the hacienda saved his life, then substituted the body of a man who had died naturally that night; Bonney then lived the rest of his life peacefully under the name John Miller. Another version claims that Garrett and the Kid had become close friends years earlier in Beaver Smith’s Saloon and that Garrett had helped

set up this elaborate ploy, to enable Billy to live the rest of his life in peace. And from time to time, through the succeeding years, men would show up in the saloons of the Old West claiming to be Billy the Kid, saying they’d miraculously escaped death at the end of Pat Garrett’s six-shooter that night—

And, by the way, would you buy me a drink?

The most publicized claim was made in 1949, when a ninety-year-old man from Hamilton County, Texas, William H. “Brushy Bill” Roberts, stated that his true identity was, in fact, Billy the Kid. The man killed that night in 1881, he said, was a friend of his, known as Billy Barlow. He himself had lived in Mexico until things cooled down, then led a life of adventure. He’d served with Pancho Villa in the Mexican Revolution, worked in

Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show,

joined Teddy Roosevelt’s Rough Riders and fought in Cuba, and even served as a US marshal while marrying four times and living under a dozen aliases. Although Roberts died of a heart attack in 1950, the book detailing his story,

Alias Billy the Kid,

was published in 1955. Although it was generally dismissed at that time, years later, the full transcripts of interviews conducted before his death seemed to make a much more convincing case.

Brushy Bill told an entertaining story. Although there was compelling evidence that “Brushy Bill” was actually a man named Oliver P. Roberts, who was born in 1879, other evidence seems to indicate that William Roberts had intimate knowledge of Lincoln City and many of the events that took place there. In face, there is more hard evidence to support the claim that William H. Roberts was indeed Billy the Kid than there is evidence that Pat Garrett actually killed the Kid the night of July 14, 1881.

In 2007, a legal effort was launched to settle the story once and for all by exhuming the remains in Billy Bonney’s grave and attempting to match the DNA to that of his mother. That request was denied. Although it is still generally accepted that the legendary life of William H. Bonney, alias Billy the Kid, ended in the darkness of Pete Maxwell’s bedroom, there remain enough unanswered questions to make this one of the Wild West’s most compelling mysteries.

BUTCH CASSIDY