Bill O'Reilly's Legends and Lies (30 page)

Read Bill O'Reilly's Legends and Lies Online

Authors: David Fisher

Actually, the many millions of Indians living on the North American continent when Europeans arrived generally left the newcomers alone. In fact, an early problem faced by settlers was that too many of them wanted to leave the settlements and live among the tribes. Ben Franklin said, “No European who has tasted Savage life can afterwards bear to live in our societies.”

Most of the tribes didn’t care very much about the settlers; they were too busy fighting other tribes. In some ways, theirs was a relatively sophisticated society: Hundreds of years before the American Constitution

was written, the Iroquois Great Law of Peace apparently included the freedoms of speech and religion, a separation of powers in government, and the right of women to participate in government. Prior to the American Revolution, the relationship between the largest tribes and the British was good; the Indians even adopted some elements of the British lifestyle and

farming techniques. And when that war erupted, they fought alongside the British to maintain that relationship.

This 1776 illustration depicts a British Loyalist and American colonist fighting over a banner, while a Native American watches what he believed to be a battle over Indian lands. The Indians sided with the British, anticipating that a British victory would end westward expansion.

Following the Revolution, the question that was to shape this new nation—Who owned the land on which the Indians lived?—was strongly debated. George Washington’s secretary of war, Henry Knox, believed that “the Indians being the prior occupants, possess the right of the soil.”

Responding to President Monroe’s attempts to buy their land, a Choctaw chief laid out the Indians’ desire: “We wish to remain here, where we have grown up as the herbs of the woods; and do not wish to be transplanted into another soil.”

The Indian wars that would spring up like brush fires across the continent for most of the nineteenth century began in the Southeast after the British surrender at Yorktown. But by 1830, all the tribes east of the Mississippi had been pacified, and those tribes were “removed” into the Indian Territory. Andrew Jackson had promised the Indians that the land would be theirs “as long as grass will grow green and the river waters will flow.” In actuality, within a decade, more than four million white settlers had crossed the Appalachians into the vast Mississippi valley.

The government negotiated several treaties with the Indians, then proceeded to break those pacts when the land became valuable. The terrifying—then, years later, thrilling—fighting began with the discovery of gold in the Dakotas in 1849 and the decision to build a transcontinental railroad. Great Plains tribes such as the Lakota Sioux, Navajos, Cheyennes,

Comanches, Apaches, Kiowas, and Arapahos lived and hunted on those lands and fought to protect their way of life. But mostly they fought soldiers, not settlers. Although attacks on wagon trains were common in dime novels, Wild West shows, and movies, they were uncommon in real life. It’s estimated that fewer than four hundred settlers were killed in Indian attacks, and the settlers probably killed an equal number of Indians. Settlers were much more likely to hire Indians as guides or trade with them than fight them.

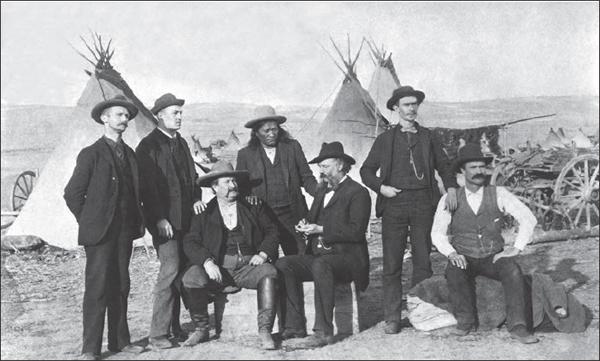

As the tribes settled on reservations, government Indian agents and traders arrived, both to provide assistance and to exploit them whenever it was possible.

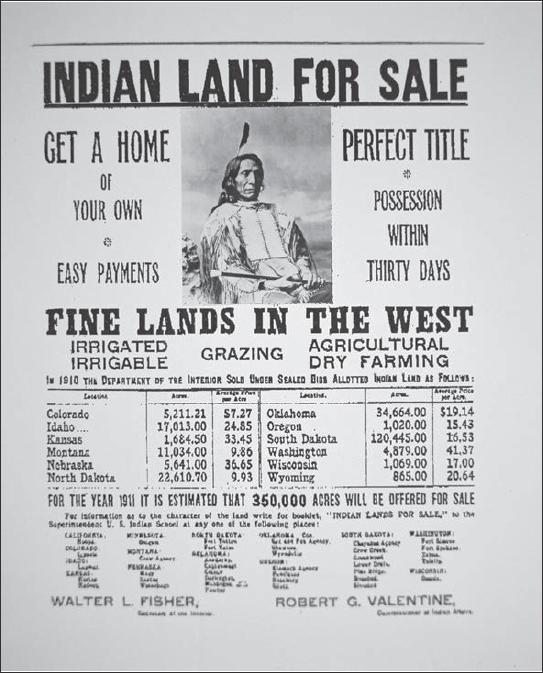

The Dawes Act of 1887 and ensuing legislation allowed the federal government to sell lands to white settlers that had already been granted by treaty to the tribes. This 1911 poster offers settlers “fine lands in the West” for easy payments.

But the fighting between the army and the Plains Indians was brutal. General Sherman gave his troops orders to kill all Indians—and even their dogs—and burn their villages to the ground. When that failed, the cavalry killed the buffalo to starve the Indians into submission. In 1890, the Census Bureau estimated that in the forty different Indian wars, nineteen thousand white men, women, and children had been killed, along with at least thirty thousand Indians. But the real number of Indian dead is likely in the hundreds of thousands, as countless more tens of thousands died of disease and other factors during long forced marches to designated lands.

Although it is understood that the victors get to write the history, in recent years, Americans have reassessed the country’s victory in the Indian wars. Many people have gained a greater understanding of the Indian point of view, perhaps best explained by Chief Black Hawk, who said, upon his surrender in 1832, “We told them to leave us alone, and keep away from us; they followed on, and beset our paths, and they coiled themselves among us, like the snake. They poisoned us by their touch.”

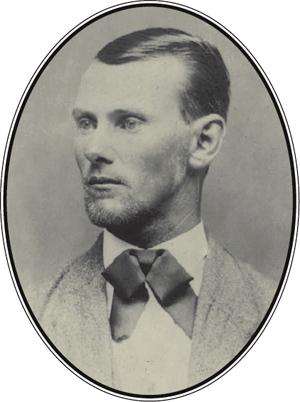

JESSE JAMES

On December 7, 1869, “a mist like pall” hung over the small town of Gallatin, Missouri. “The city,” reported the

Booneville Weekly Adventures,

“was veiled from sight by the dense fog that prevailed, and an unusual stillness and quiet pervaded every quarter of the little city.” Out of that fog and into legend rode the outlaw brothers Jesse and Frank James.

They dismounted and hitched their horses at the water trough in front of the Daviess County Savings Association. At twenty-six, Frank was four years older than Jesse; both brothers had ridden hard through the Civil War and its aftermath. And they hadn’t forgotten for a bit what they’d seen and who had done them wrong. They intended to steal the money in this bank, no question about that, but that was not their main reason for being there. They had come to avenge the killing of a friend.

The owner of the bank, former Union captain John W. Sheets, was sitting at his desk in conversation with lawyer William McDonald when the James brothers walked through the door. As Sheets got up to greet these customers, McDonald started to leave. The two men cornered Sheets and pulled their six-shooters. They told him why he was about to die: He had caused the death of their former commander and good friend, “Bloody Bill” Anderson, and they were bound by oath to avenge it. The James brothers then shot him twice, once in the head and once in the heart. When the lawyer McDonald started running, they winged him in his arm, but he got away. Then they grabbed several hundred dollars from the safe and till and took off. A posse pursued them out of town and shots were exchanged. One of the James brothers fell from his horse, which galloped away, but the other brother grabbed his arm and swung him up onto

his

horse, and they outraced their pursuers. As the

Kansas City Daily Journal

reported, “There is a boldness and recklessness about this robbery and murder that is almost beyond belief.”

It turned out that Jesse and Frank James had made a mistake—they had killed the wrong man. Although Sheets had been on the team that tracked down and ambushed the murderous Anderson, in fact, it was Major Samuel Cox who deserved credit for bringing an end to Bloody

Bill’s reign of terror. Not that the James brothers cared particularly; killing came pretty easily to them. And the result of this bank robbery was far greater than they could have imagined: It made Jesse James famous.

Although bank robberies weren’t uncommon, this was such a cold-blooded killing that Missouri governor Thomas T. Crittenden offered the largest reward in state history, ten thousand dollars, for the capture of the outlaws. Among those who read the breathless newspaper account was the founder and editor of the

Kansas City Times,

John Newman Edwards.

In Jesse James, John Edwards found the man he had been looking for. During the war, the James brothers had served with Bloody Bill, who commanded one of the Confederacy’s most successful—and vicious—guerrilla units. As an element of Quantrill’s Raiders, they had participated in the Centralia massacre, in which more than a hundred Union troops had been slaughtered. After the war, Jesse and Frank James essentially refused to surrender, instead hitting the outlaw trail.