Bill O'Reilly's Legends and Lies (15 page)

Read Bill O'Reilly's Legends and Lies Online

Authors: David Fisher

Technological advances in printing in the 1840s had made it possible to inexpensively produce numerous copies of a book. Cheap and easily carried, dime novels were extremely popular among Civil War soldiers looking for any diversion, and soon people everywhere were seeking them out.

The initial success of Beadle’s books caused competitors to rush to publish their own, which often were stories that previously had been

serialized in three-penny dailies or story newspapers. Although these books were called dime novels, some of them sold for a nickel or less. The character of the virtuous cowboy fighting vicious Indians and ruthless outlaws grew out of the early stories of heroic frontiersmen, in particular, James Fenimore Cooper’s Leatherstocking Tales. To compete, authors had to continuously up the ante, putting their characters into increasingly dangerous situations and then giving them the almost superhuman skills needed to survive for another book. These sensationalized action-adventure stories often were based extremely loosely on real events and used real names—and turned men and women such as Buffalo Bill, Wild Bill Hickok, Bat Masterson, Calamity Jane, and even Belle Starr into American celebrities.

Although inexpensive “yellow-backed” paper books had been published earlier, dime novels—and the nickel or “half-dime” novels that followed—generally were published as numbered volumes in series that featured recognizable characters. More than 40,000 different titles were published, many of them by Beadle and Adams, who warned potential authors, “We prohibit what cannot be read with satisfaction by every right-minded person—old and young alike.”

These books were the original pulp fiction, written to be devoured in one gulp and quickly forgotten. Millions of copies were sold. Edward Judson, writing as Ned Buntline, could write a book in a few days and published more than four hundred of them, transforming Buffalo Bill into a legendary figure. The most successful dime novelist was probably Edward Ellis, whose

Seth Jones; or, the Captives of the Frontier,

sold six hundred thousand copies in six languages.

By the time dime novels disappeared early in the twentieth century, the character of the valiant cowboy defeating evil at the last possible moment was forever enshrined in our culture and had become the symbol of the Old West recognized throughout the world. The movies picked it up from there, and the rest has become history!

WILD BILL HICKOK

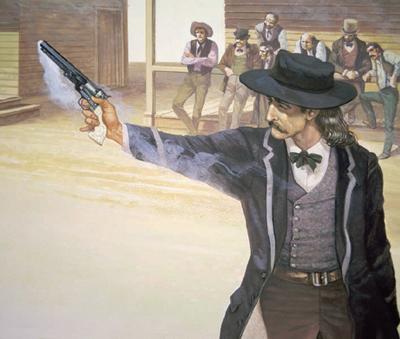

In the settling heat of an early summer evening, at six o’clock on the twenty-first of July, 1865, Wild Bill Hickok stood calmly in the center of the Springfield, Missouri, town square, his Colt Navy revolvers resting easy in a red sash tied around his waist, their ivory handles turned forward. About seventy-five yards away, the gambling man Davis K. Tutt stepped out of the old courthouse, where he’d been settling some fines. The two men stared at each other. Even at that distance, Wild Bill could see the old Johnny Reb Tutt slowly pull a gold watch out of his vest pocket and glance nonchalantly at the time—the very watch that Hickok had warned him not to display. Hickok yelled to him, “Don’t you cross the square with my watch!” Tutt responded by slipping the watch back into his pocket and stepping out into the middle of the square. Neither man was the type to back down from a challenge. They faced each other: Dave Tutt turned to his side; Wild Bill squared his shoulders and stood facing straight ahead. For a few seconds, nothing happened. Then they went for their guns.

This story of the first showdown in the Old West has been carried by the winds for one hundred fifty years, and in all that time the details tend to get a bit murky. According to legend, the two men had met the night before at the Lyon House Hotel, where Tutt had demanded that Hickok settle a $35 debt. Hickok insisted that he owed the man only $25, but until the debt could be settled, Tutt took Hickok’s gold watch as collateral. Hickok accepted the deal but warned Tutt not to embarrass him by flaunting that watch in public. There was nothing wrong with losing at the table and paying your debts, he knew, but he was not a man who stood by quietly when held up for ridicule.

Legend has it that Tutt wasn’t too interested in the correct time when he pulled it out of his vest; he was instead calling Hickok’s bluff.

But others claim that the real reason for this feud was lady troubles. Some said that when Hickok had a falling-out with a woman he was courting named Susannah Moore, Dave Tutt had taken advantage of the situation and waltzed in between them. In response, Hickok had struck up a relationship with Tutt’s sister. Whatever the reason, there was bad blood

between the two men and it was going to end that afternoon. Contrary to the movies and TV Westerns, quick-draw showdowns on main streets were very rare. This was the first one, and it appears that a lot of the townspeople turned out to watch it.

Most reports claim that both men pulled their guns evenly, but, rather than firing wildly, they took their time to aim—then fired simultaneously, their respective volleys sounding like a single shot. “Tutt was a famous shot,” said an observer, known in those parts as Captain Honesty, “but he missed this time; the ball from his pistol went over Bill’s head … Bill never shoots twice at the same man, and his ball went through Dave’s heart.”

Tutt shouted to bystanders, “Boys, I’m killed!” then fell dead.

After he’d fired, Hickok whirled to face Tutt’s men, who were standing nearby and looked ready to draw. “Put up your shootin’ irons,” he warned, “or there’ll be more dead men here.”

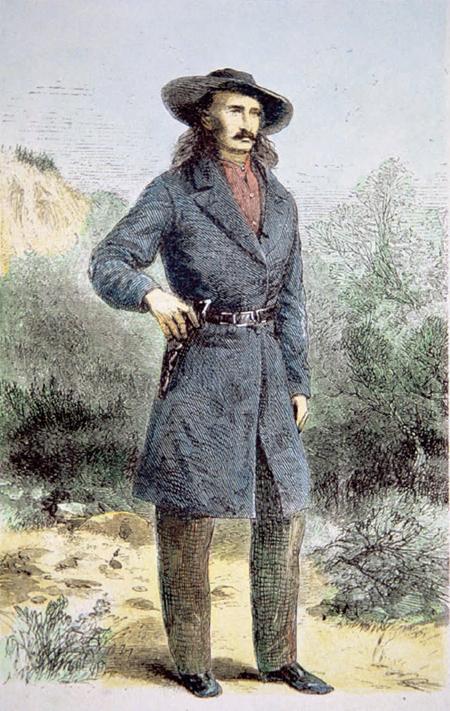

They reluctantly put down their weapons. And the legend of Wild Bill Hickok, “the Prince of Pistoleers,” already well established, began to grow. James Butler Hickok was the most famous gunslinger of the Old West; a man known to be reluctant to shoot, but when it became necessary, his draw was “as quick as thought” and his aim was always true. He was the man boys grew up wanting to become; a man of courage and honor whom other men proudly stepped aside for, then bragged they’d met; a man of such grace and bearing that he made women swoon. The fetching Libbie Custer, General Custer’s widow, with whom Hickok may have dallied, wrote of him,

Physically, he was a delight to look upon. Tall, lithe and free in every motion, he rode and walked as if every muscle was perfection, and the careless swing of his body as he moved seemed perfectly in keeping with the man, the country and the time in which he lived…. [H]e carried two pistols. He wore topboots, riding breeches and dark blue flannel shirt, with scarlet set in front. A loose neck handkerchief left his fine firm throat free [and] the frank, manly expression of his fearless eyes and his courteous manner gave one a feeling of confidence in his word and in his undaunted courage.

Fame sometimes has a lot of sharp edges and has to be handled carefully. Hickok’s reputation as a deadly gun followed him throughout his life, wherever he traveled, and brought with it some heavy challenges. And some people wonder if, on his last day, it was that fame that caused his demise.

In his lifetime, Hickok became the embodiment of all the virtues attributed to the great men who fought to settle the West, a man who stood up for what was right. He was born in 1837, in the frontier town of Homer, Illinois. His parents, William Alonzo and Polly Butler Hickok, were abolitionists who risked their lives by turning their home into a station on the Underground Railroad. The Hickok family often hid slaves in cubbyholes dug out under their floorboards and, when necessary, carried them to the next station in their wagon. It was said that the Hickoks provided for dozens, maybe even hundreds, of escaping slaves.

This was the image of the gunfighter Wild Bill Hickok that thrilled Americans: “'Wild Bill’ Hickok (1837–76) demonstrates his marksmanship with his Colt Navy model revolver.”

Even as a young man, Hickok was known to be a sure shot, and when he was still a teenager he rode with the Jayhawkers, an antislavery militia fighting in the Kansas Territory. There he became known as Shanghai Bill because of his height and his slim frame, but the name didn’t stick. It was there that he purportedly first met his lifelong friend William Cody,

a twelve-year-old boy who years later would gain fame as Buffalo Bill, but who was then scouting for the army. The way Cody told the story, he was being bullied by some local toughs and Hickok stepped into the situation and walked him out.

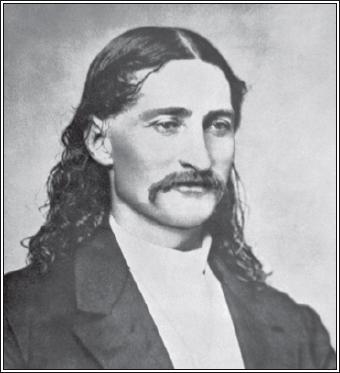

This was the first published image of Wild Bill Hickok, Alfred Waud’s lithograph, as it appeared in

Harper’s Magazine,

1867.

William Hickok’s legend had its origins in the summer of 1861 at the Pony Express station in Rock Creek, Nebraska. Speculation abounds concerning what actually happened there, and over time the tales have gotten taller. The twenty-four-year-old Hickok had been driving freight wagons and coaches along the Santa Fe Trail for Russell, Majors, & Waddell, the parent company of the Pony Express, until he got into a tussle with a bear; when his shot ricocheted off the bear’s head, Hickok rassled it and cut its throat, but not before that bear inflicted some serious damage. While recuperating, Hickok did odd jobs at the relay station, tending to horses and wagons for station manager Horace Wellman. Hickok lived with Wellman and Wellman’s wife, Jane, in the station’s small cabin, which had been built on land Wellman purchased from a local rancher named David C. McCanles. McCanles was an ornery fellow, who insisted on derisively calling Hickok “Duck Bill,” supposedly a reference to his large, narrow nose and protruding lips—and another name that didn’t stick. Naturally, being made fun of did not sit well with Hickok. One day McCanles showed up at the station with his son, Monroe, and two members of his gang, demanding his land back because Wellman was late on his payments. But, once again, another version of the story says that the real reason McCanles showed up concerned the affections of a young woman who had taken a liking to Hickok.