Bill O'Reilly's Legends and Lies (39 page)

Read Bill O'Reilly's Legends and Lies Online

Authors: David Fisher

Whatever chance Billy Bonney might have had for a decent life ended when he was fourteen years old and his mother died of tuberculosis. He stayed in Silver City for a short time after that, cleaning and washing dishes for neighbors who owned a hotel. His life was pretty much a scuffle; he didn’t appear to have any particular destination. Although he didn’t show much promise, he also didn’t appear to be a bad sort. He fell in with the Mexican community and fully embraced its vibrant culture. Like most young men, he loved to dance and party. On occasion, he displayed a temper. The Mexicans called him El Chivato, “the Rascal.” He committed the sort of minor offenses that have long been associated with teenagers: Once he was caught stealing cheese; another time, he was arrested for holding shirts a friend of his known as “Sombrero Jack” had stolen from the Chinese laundry run by Charley Sun and Sam Chung. Sheriff Harvey Whitehill put him in jail for that, figuring he’d give him a good scare, but instead he shimmied up and out of the jailhouse chimney and took off for a sorry future.

He kicked around the area, finding work as a ranch hand and shepherd until he fell in with John R. Mackie, a small-time criminal whose gang consisted mostly of teenage boys. Mackie might have recognized the possibilities in the young man: Billy Bonney had a slight build and a winning way about him. People took to him easily; his smallish stature was nonthreatening, and his easy smile was reassuring. But when it was necessary, he was quick on the draw and known to be an accurate shot. The gang stole horses and cattle from the government in Arizona and sold it to the government in New Mexico; then they would steal stock in New Mexico and take it to Arizona. However, on the night of August 17, 1877, seventeen-year-old Billy Bonney’s life of crime took a more dangerous turn.

He was playing cards in George Atkin’s cantina in Camp Grant, Arizona, with a blacksmith named Frank Cahill. Cahill’s big mouth, which had earned him the nickname Windy, was working hard that night, throwing a string of insults at Bonney. Cahill was a small man with blacksmith’s muscles and a mean temper. In some stories, the fight started because of a gambling disagreement; in others, as the result of drink; and in still others, Cahill called Billy a pimp, and Bonney responded by calling him a son of a bitch. Whatever the cause, suddenly Windy Cahill grabbed Bonney and threw him hard to the floor. The Kid got up, and Cahill pushed him down again. Billy got up once more, and Cahill shoved him a third time, but this time Cahill jumped on top of him and pinned his shoulders to the floor. Then he started punching him, again and again. The Kid had no chance of winning this fistfight, but somehow he managed to pull out the peacemaker he carried, a Colt .45, and fired one shot into Cahill’s chest. Cahill slumped over and died the next day. Billy was locked up in the camp’s guardhouse.

William Henry Bonney likely earned his nickname Billy the Kid after this shooting. It obviously was based on his youthful appearance. Fully grown, Billy Bonney stood five-foot-seven and weighed no more than 135 pounds; he was described by newsmen as “slender and slight, a hard rider and active as a cat.” Other reports described him as “quite a handsome looking fellow, the only imperfection being two prominent front teeth slightly protruding like a squirrel’s teeth.” Although the shooting of Cahill appeared to be a case of self-defense, the Kid didn’t wait around for the law’s decision. Instead, he slipped out of the guardhouse and took off for New Mexico. That turned out to be the right move. After hearing the evidence, a coroner’s jury ruled that because Cahill wasn’t armed, the shooting was “criminal and unjustifiable.” Billy the Kid was wanted for murder.

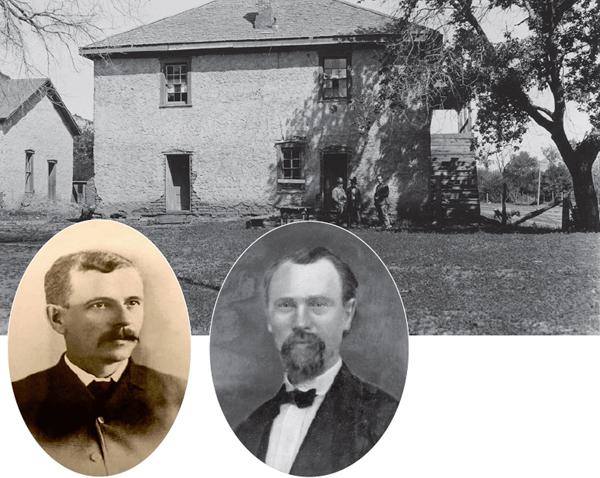

He stopped running when he reached Lincoln County and hired on with merchants and cattle ranchers Major Lawrence G. Murphy and James J. Dolan. Lincoln County consisted of thirty thousand square acres of some of the best cattle-grazing land in the country. Murphy and Dolan ran a large mercantile business, known as “the House” in honor of the mansion that served as their office. They were in fierce competition with newcomers Alexander McSween and John Tunstall, who were backed by the legendary cattle baron John Chisum. Their rivalry involved much more than money: The Irishmen Murphy and Dolan did not take kindly to the Englishman Tunstall trying to cut into their business. The fight between these two factions was known as the Lincoln County War, and Billy the Kid found himself right in the middle of it.

Initially he joined a gang of mostly teenage cattle rustlers run by gunman Jesse Evans; they called themselves “the Boys.” It was a rough group, known to have committed several

murders. The Boys had been hired by the House to steal cattle from Chisum’s Jinglebob Ranch, which would then be sold to Mexicans and Indians. At first, McSween and Tunstall tried to fight back legally, but when the law failed them, they hired their own guns.

Somehow John Tunstall recruited Billy onto his side; one story claims that Billy was caught stealing a horse or cattle belonging to Tunstall and was arrested. Rather than put him in prison, Tunstall offered him a choice. If he agreed to testify against other members of the Boys, Tunstall would give him a job. It was a chance to make an honest living. Tunstall wasn’t much more than a kid himself, being about twenty-four, and most reports indicate that he and Billy took a strong liking to each other. Apparently Tunstall once said, “That’s the finest lad I ever met. He’s a revelation to me everyday and would do anything to please me. I’m going to make a man out of that boy yet.”

When William Bonney reached Lincoln County, he hired on as a hand with merchants and cattlemen James Dolan and Major Lawrence Murphy, who ran their operation out of this mansion, known as the House.

Eventually Billy went to work for John Tunstall, whose efforts to compete with the House led to the Lincoln County War. When Tunstall was murdered, the Kid declared his own personal war on the House.

He never got the chance to do that. On February 18, 1878, Tunstall and several hands—Billy might have been among them—were driving nine horses to Lincoln on the Rio Feliz when they were cut off by a posse that had been deputized by Lincoln sheriff William Brady and included several members of the Boys. These killers now had the law backing their moves. At first, the Boys claimed the horses had been stolen, but clearly that was only a ruse. Three of them managed to isolate Tunstall in the brush, and when the shooting stopped, Tunstall’s body was found lying in the dirt next to his buckboard, one shot in his breast and a second shot in the back of his head.

When Billy the Kid learned of the murder, he said, “He was the only man that ever treated me kindly, like I was born free and white,” and then vowed, “I’ll get every son of a bitch who helped kill John if it’s the last thing I ever do.”

Lincoln County justice of the peace “Squire” John Wilson swore in a posse of special constables, headed by ranch owner—and Tunstall’s foreman—Dick Brewer, to arrest Tunstall’s killers. Billy the Kid joined this group, “the Regulators,” as they became known, when they set

off to dispense justice. It was a very strange situation, two legally deputized posses hunting each other. The Regulators struck first, arresting two of the House’s men and then killing them, allegedly as they tried to escape. The escalating war reached a new level about a month later, when Billy the Kid and five other Regulators ambushed and killed Sheriff Brady and his deputy as they walked down the street in Lincoln. Billy was slightly wounded in the gunfight. Although Brady was known to be sympathetic to the House, killing a lawman was serious business, even in a lawless environment, and people turned away from the Regulators, believing them to be no different than Murphy and Dolan’s men.

Over the next months, both sides lost men. Dick Brewer was killed during a shoot-out at Blazer’s Saw Mill, in which House man Buckshot Roberts also died. Frank McNab, who replaced Brewer as captain of the Regulators, was killed a month later; in return, Manuel Segovia, who was believed to have murdered McNab, was tracked down and killed, again allegedly trying to escape. The US cavalry joined the fight on the side of the House, giving their gunmen both legal cover and added firepower. Although nobody knows if Billy the Kid actually did any of the killing, it was agreed that he never held back.

Although there is a lively market in Billy the Kid Wanted posters, most of them were created to take advantage of his fame after his death. The facts here are accurate, but the only verified “poster” was a reward notice published in the

Las Vegas Gazette.

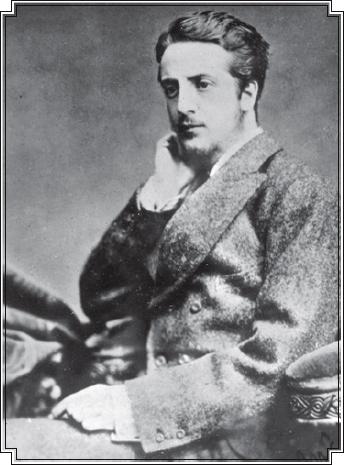

This 1880 illustration from the

Police Gazette

portrays Billy the Kid killing a man in a saloon, probably referring to the shooting of Joe Grant. The

Police Gazette

was known for its illustrations and photographs of popular criminals and scantily clad women.

The Lincoln County War came to a head at the five-day-long battle of Lincoln. On July 15, about forty of Dolan’s men laid siege to McSween’s house, where he was holed up with at least fifteen men. Supposedly, during a lull in the fighting, a House man called out to Billy to surrender, claiming he had a warrant for his arrest for the murder of Sheriff Brady and his deputy. Billy was said to reply, “We too have warrants for you and all your gang which we will serve on you hot from the muzzle of our guns!”

For three days, the town was a battlefield; then a column from Fort Stanton under the

command of Colonel Nathan Dudley joined the fight on the side of the Dolans. Two days later, McSween’s house went up in flames. McSween stepped out into his yard and was shot nine times. Several Regulators were killed attempting to escape the fire. But Billy Bonney was among the Regulators who slipped out the back and made it across the river.

News of the Lincoln County War was reported throughout the nation, and Billy the Kid—the murderous teenager—quickly caught the fancy of the public. In those stories, he was given credit for even more killings than he was known to be responsible for, ensuring his reputation while selling newspapers and novels.