Big Sex Little Death: A Memoir (4 page)

Read Big Sex Little Death: A Memoir Online

Authors: Susie Bright

She was the first in the family to marry outside of the faith, to divorce, to bear only one child. More important, she didn’t die bearing children — the number one cause of death among Halloran women.

She played footsie with my father in Greek class. She was the first girl he ever kissed. She and he agreed, in separate conversations with me, that he was the only straight man studying classical languages and anthropology at the University of California. When I “came out” to my parents, it was anticlimactic — together, they’d had far more of a gay social life and witnessed more emerging queer history after World War II than I’d seen in my lifetime. They preferred gay life, intellectually, socially, but were really relieved to find each other, an erotic and intimate connection in an otherwise

lavender universe. My dad would say, “I wondered if I was gay. But I dreamed about Rita Hayworth, Esther Williams, and your mom.”

My mom would never have described herself as a fag hag: first of all, because she would never, ever use an epithet, no matter how good-natured; and second, because she really thought of herself as Lucy Van Pelt, completely fed up with virtually everyone.

When my aunt Molly died, the one sister who didn’t let my mother disappear altogether, I found out that Molly had collected what was left of the family scrapbooks. I was amazed to find a “baby book” for my mom and her brother, which their mother, Agnes, had kept until the first two kids were toddlers. I was shocked at the prosperity the little book implied. How could they have kept a lovely illustrated diary like this when a few years later my mom was on the street collecting rice from relief wagons with her head hanging down?

My grandmother Agnes died in my twelve-year-old mother’s arms while the little ones screamed. Her family’s farm had been foreclosed on, and her husband had abandoned her.

But in her teens, my grandmother had had another life. She was the glamorous Nickelodeon piano player, Fargo’s one-and-only. When Agnes was first married, things were … okay. She had the time and good health to make a baby book. Her husband Jack’s writing was beautiful and filled some of the pages with their first two children’s accomplishments. Jack was selling tractors for John Deere, and he would send perfectly fountain-penned postcards from the road: “Wish you were here; kiss the babies.”

“Yes, he was famous for his hand,” my mom admitted when I showed her the evidence that her father once had been something more than a complete basket case.

She looked at the postcard I showed her as if it was a museum piece, not connected to her. How could this be the same guy who hid out and let the orphanage come pick up the children when his wife died, the man whose hands shook in photographs, the one who looked like Ichabod Crane in his black duster?

The baby book was composed before the crash, in the mid-twenties, before the banks took Grandmother Halloran’s farm, before skid row claimed my grandfather’s allegiance. The baby books were full of promise. On the page where the doting parents record Baby’s First Word, instead of “Da” or Mama,” Elizabeth first word was: “Bud.” Written in that beautiful cursive pen.

When my mom was dying a few years ago, she was on a lot of morphine, and she gaily told stories I’d been waiting to hear all my life. I wasn’t ready for it; I’d given up so long ago ever hearing anything from her lips.

When I was a child in Berkeley, I would make the mistake of asking, “What was it like when you were my age?” She’d cry as if I’d stuck her with a pin, her face accusing me, as if she was the little one and I was too cruel. I didn’t ask her again after I was old enough to read.

When my mother died, cancer protruding all over her body in giant lumps and bumps, she wasn’t grieving. She could recite a chapter of her life without blinking, even laughing at it. She didn’t cry at all, except when she was looking for her grandmother, in bouts of sleepwalking.

I realized after one of her nocturnal walks that my mom could barely remember her birth mother, because her only childhood memories were of a sick and dying woman who kept getting pregnant. “Mama” was a saint, not a person.

Instead, my mom looked to her real mother figure, her grandmother. “My grandma,” she told me, during one of her loquacious Fentanyl-patch moments, “was the only person in my family who ever praised me or told me I was good. She told me I was smart and I could do anything.”

Forty-plus years it took to hear that.

My mother was a star; when I meet people who still remember her, they shake their heads and remember an incandescent anecdote, where she burned hot, either in temper or passion or blistering empathy. She felt things so deeply, and she could bury them just as long.

Elizabeth told me a story one morning, when we were meditating on the plum blossom outside her window. “When Grandma still had the farm,” she said, “there was a fence at the edge of the property right on the highway, where the Greyhound bus passed every day on its way west.

“There was a song on the radio I liked then — it was Jules Verne Allen, that Texas cowboy — “The Red River Valley.”

I’ve been thinking a long time, my darling

Of the sweet words you never would say

Now, alas, must my fond hopes all vanish

For they say you are going away

“I would sit on that fence post every afternoon!” She laughed as if the memory of her legs swinging on the fence was a comic newsreel. “I was waiting for the bus to come by, bawling out ’The Red River Valley’ at the top of my lungs — because I knew that one day, th

e bus driver would hear me, and everyone on the bus would clap their hands and they’d stop the bus and pick me up and take me out to Hollywood, where I would be a big star!”

I can see the plow behind her, and our California destiny — way, way out, in front of those wheels.

Way Out West

W

hen I was a little girl and asked Grandma Bright, my dad’s mother, where the Brights came from, she said one word: “Kansas.”

I was hoping for a thrilling immigrant experience, like my mother’s — but no, it was the Bright story, an undramatic yawn.

I appreciate my grandmother Ethel now. I’d give anything to sit next to her at my sewing machine or eat one of her egg salad sandwiches. But as a child, although I didn’t see her very often, I thought the lives she and my grandfather Ollie led were dull. My dad, Bill, had me for school vacation visits a couple times a year, and we would always visit Oxnard to see his folks. Oxnard, at the time, was like the Wichita of California.

We had cottage cheese and peaches for lunch. Grandma wouldn’t eat spaghetti because it was a “foreign” food. She made enormous quilts and braided rugs from scraps, all day, every day, plus dozens of aprons and potholders perfectly stitched with rickrack. No store-bought clothes, ever. She canned everything; and since most of the Brights were farmers, there was a lot to can. She let me put on her big smock and go out and pick berries, or take a hoe and make rows in the garden beds. It was the same thing, every day, every visit. Her peanut butter and jelly sandwiches were mitered as neat a

nd perfect as every square on one of her quilts.

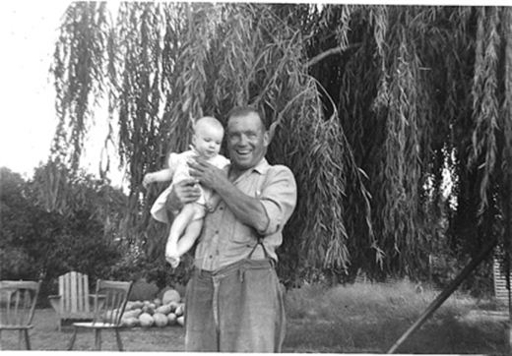

My grandpa was a butcher and ran a chicken ranch. They had meat on the table every day during the Depression. Ollie was the one who gleefully called me “Susie,” first thing from the hospital, ruining my parents’ intentions to call me “Susannah” in all its three-syllable glory. “Susie” stuck. You can see photos of him lifting me in the air, under the big willow tree in their back yard, his dirty suspenders and dungarees fit to burst, a huge smile on his face.

I would love to remember that smile, and I do feel it when I look at the old snapshots. But by the time I could remember visiting my grandparents, my grandpa didn’t say a word — he had been rendered mute by Parkinson's disease — and he sat in a living room La-Z-Boy, his mouth a thin tight line. I was afraid of him. His hands trembled all the time, and when Grandma helped him to the kitchen to eat, his fingers clattered on the formica tabletop. Grandma would heat paraffin wax every morning and evening for him to soak his fingers and feet in.

He spent a decade in this condition before his death, which was my introduction to the cruelty of “being kept alive whether you like it or not.” Why would no one talk about it? I knew that my grandpa — who’d loved life so much, who’d sing “Golden River” and drive a plow, who couldn’t wait to get a Model T and drive to the seashore — had never wanted to be in a chair watching Lawrence Welk reruns. But that’s how everyone acted in Oxnard — you kept going because you had to keep going and you did not question the rules.

My stepmother Lise said to me once that she had never met anyone who had as much enthusiasm for life as my dad.

I think he got that from Ollie. There’re pictures of my grandpa as a young soldier during World War I in Paris, grinning from ear to ear and feeding a flock of birds in the plaza. He always wanted to travel, be on the move. Bill said that when he went into grad school and stored all his college books back at his folks’ home in Oxnard, his father read every single one and would call him at night, peppering him with questions.

My dad didn’t have the nerve to admit he hadn’t read every page of every book in his collection. After all, Ollie had bought the family a red-leather forty-volume set of the Encyclopedia Britannica and actually read it — the whole thing. He couldn’t imagine buying a book without devouring it. And besides, it would be a waste of money.

My grandpa was the oldest living son in a clan of eight surviving kids, the valedictorian of his high school. But he wasn’t able to look forward to college. His parents were ill and he went to work, along with his other siblings, until he was drafted.

Oliver was determined that his son Bill become a scholar, a traveler — and that he never, ever be involved in the family trade. My dad didn’t know a steak from a chop — he was never allowed behind the counter of the butcher store. “Go do your homework, Billy,” they’d say, leaving him to his books and the radio and the Nickelodeon and the record player.

At the time, he had no complaints because he loved those things. Every nickel went to the movies; every recording and magazine was treasured. But when I was a teenager and Bill talked to me about his life, he said he regretted feeling so physically inept in a family of big men, powerful men, who used their hands for everything.

He told me the worst mistake his parents made, unwittingly, was skipping him a grade and a half, putting his prepubescent self among the older and more jaded upperclassmen.

“I didn’t fit in at all with the older kids — it was a disaster. I was beat up every day in gym; it was torment. I couldn’t play their games or hold my own — my only friend was your godfather, Bob Thiel, who grew up across the street from me.

We would listen to opera and classical music and swear we were going to get out of Oxnard … someday.”

Two generations later, my daughter had the same assignment in third grade that I’d received at her age: “How did your family come to California?” I was determined to pierce the “Kansas” cul-de-sac, and so I encouraged her to press my dad for more information on his side of the family.

Bill told Aretha a different story, alright, the oldest story I’d ever heard of our ancestors. Just think: All those Bright people, all those dusty photographs of characters whose names I don’t know, so much life in them, and this is the one story that survived, passed only in the oral telling.

Aretha’s great-great-great-grandfather, William Riley Bright, took his family to California from Kentucky in the 1800s, by wagon train. They faced every peril and deprivation along the trail.

William Riley was a tough old bird, and he almost met his match. One day on their travels, climbing the Rockies, an eagle swooped out of the sky and plucked Bill Riley’s right eyeball clean out of his head!

Did that stop him? Of course not. He arrived with his family, one-eyed, on the central California coast, in Ventura County.

I think a lot about that toughness. My dad regretted losing a piece of it, although he treasured the soft intellectual fields he was let loose in. He got to do everything his father every dreamed of, and more. And he kept more of his connection to California than he even recognized. Sometimes we’d go backpacking in the Sierras — and he knew how to do everything in the mountains, it seemed to me. He knew how to live in the desert. There wasn’t a patch of California he hadn’t explored, often first with his dad. He wasn’t a city person like my mother, who had grown up in an urban ghetto.

I’d say, “You’re a mountain man; you know every plant and animal here — you did fall closer to the tree than you think.” It pleased him to hear that.

When I first settled with my daughter and partner in Santa Cruz in 1994, where I live now, I took my dad to the Boardwalk. It’s like a small, West Coast version of Coney Island … games of chance, a huge wooden roller coaster. Bill told me he had been on this same roller coaster in the 1930s, that his whole family had jumped in an Edsel and tooled up to Santa Cruz, a two-day journey from Oxnard. “I loved it here,” he said.