Better Than Before: Mastering the Habits of Our Everyday Lives (2 page)

Read Better Than Before: Mastering the Habits of Our Everyday Lives Online

Authors: Gretchen Rubin

Tags: #Self-Help, #Personal Growth, #Happiness, #General

There are surprisingly few of these patterns of events in any one person's way of life, perhaps no more than a dozen. Look at your own life and you will find the same. It is shocking at first, to see that there are so few patterns of events open to me.

Not that I want more of them. But when I see how very few of them there are, I begin to understand what huge effect these few patterns have on my life, on my capacity to live. If these few patterns are good for me, I can live well. If they are bad for me, I can't.

In the area of health alone, our unthinking actions may have a profound effect.

Poor diet, inactivity, smoking

, and drinking are among the leading causes of illness and death in the United Statesâand these are health habits within our control. In many ways, our habits are our destiny.

And changing our habits allows us to alter that destiny. Generally, I've observed, we seek changes that fall into the “Essential Seven.” Peopleâincluding meâmost want to foster the habits that will allow them to:

1. Eat and drink more healthfully (give up sugar, eat more vegetables, drink less alcohol)

2. Exercise regularly

3. Save, spend, and earn wisely (save regularly, pay down debt, donate to worthy causes, stick to a budget)

4. Rest, relax, and enjoy (stop watching TV in bed, turn off a cell phone, spend time in nature, cultivate silence, get enough sleep, spend less time in the car)

5. Accomplish more, stop procrastinating (practice an instrument, work without interruption, learn a language, maintain a blog)

6. Simplify, clear, clean, and organize (make the bed, file regularly, put keys away in the same place, recycle)

7. Engage more deeply in relationshipsâwith other people, with God, with the world (call friends, volunteer, have more sex, spend more time with family, attend religious services)

The same habit can satisfy different needs. A morning walk in the park might be a form of exercise (#2); a way to rest and enjoy (#4); or, in the company of a friend, a way to engage more deeply in a relationship (#7). And people value different habits. For one person, organized files are a crucial tool for creativity; another finds inspiration in unexpected juxtapositions.

The Essential Seven reflect the fact that we often feel both tired and wired. We feel exhausted, but also feel jacked up on adrenaline, caffeine, and sugar. We feel frantically busy, but also feel that we're not spending enough time on the things that really matter. I wasn't going to bed on time, but I wasn't staying up late talking to friends, either; I was watching a midnight episode of

The Office

that I know by heart. I wasn't typing up my work notes or reading a novel, but mindlessly scrolling through the addictive “People You May Know” section on LinkedIn.

Slowly, as my research proceeded, my ideas about habits began to take a more coherent shape. Habits make change possible, I'd concluded, by freeing us from decision making and from using self-control. That notion led to another key issue:

If habits make it possible for us to change, how

exactly

, then, do we shape our habits?

That enormous question became my subject.

First, I settled on some basic definitions and questions. In my study, I would embrace a generous conception of the term “habit,” to reflect how people use the term in everyday life: “I'm in the habit of going to the gym” or “I want to improve my eating habits.” A “routine” is a string of habits, and a “ritual” is a habit charged with transcendent meaning. I wouldn't attempt to tackle addictions, compulsions, disorders, or nervous habits, or to explain the neuroscience of habits (I was only mildly interested in understanding how my brain lights up when I see a cinnamon-raisin bagel). And while some might argue that it's unhelpful to label habits as “good” or “bad,” I decided to use the colloquial term “good habit” for any habit I want to cultivate, and “bad habit” for one I want to squelch.

My main focus would be the

methods

of habit change. From my giant trove of notes about habitsâdetailing the research I'd examined, the examples I'd witnessed, and the advice I'd readâI'd discern all the various “strategies” that we can use to change a habit. It's odd; most discussions of habit change champion a single approach, as if one approach could work for everyone. Hard experience proves that this assumption isn't true. If only there were one simple, cookie-cutter answer! But I knew that different people need different solutions, so I aimed to identify every possible option.

Because self-knowledge is indispensable to successful habit formation, the first section of the book, “Self-Knowledge,” would explore the two strategies that help us to understand ourselves: Four Tendencies and Distinctions. Next would come “Pillars of Habits,” the section that would examine the well-known, essential Strategies of Monitoring, Foundation, Scheduling, and Accountability. The section “The Best Time to Begin” would consider the particular importance of the time of

beginning

when forming a habit, as explored in the Strategies of First Steps, Clean Slate, and Lightning Bolt. Next, the section “Desire, Ease, and Excuses” would take into account our desires to avoid effort and experience pleasureâwhich play a role in the Strategies of Abstaining, Convenience, Inconvenience, Safeguards, Loophole-Spotting, Distraction, Reward, Treats, and Pairing. (Loophole-Spotting is the

funniest

strategy.) Finally, the section “Unique, Just like Everyone Else” would investigate the strategies that arise from our drive to understand and define ourselves in the context of other people, in the Strategies of Clarity, Identity, and Other People.

Once I'd identified these strategies, I wanted to experiment with them. The twin riddles of how to change ourselves and how to change our habits have vexed mankind throughout the ages. If I was going to try to figure out the answers, I'd have to fortify my analysis with my own experience as guinea pig. Only by putting my theories to the test would I understand what works.

But when I told a friend that I was studying habits, and planned to try out several new habits, he protested, “You should fight habits, not encourage them.”

“Are you kidding? I

love

my habits,” I said. “No willpower. No agonizing. Like brushing my teeth.”

“Not me,” my friend said. “Habits make me feel trapped.”

I remained firmly pro-habits, but this conversation was an important reminder: Habit is a good servant but a bad master. Although I wanted the benefits that habits offer, I didn't want to become a bureaucrat of my own life, trapped in paperwork of my own making.

As I worked on my habits, I should pursue only those habits that would make me feel freer and stronger. I should keep asking myself, “

To what end

do I pursue this habit?” It was essential that my habits suit

me

, because I can build a happy life only on the foundation of my own nature. And if I wanted to try to help other people shape their habitsâa notion that, I had to admit, appealed to meâtheir habits would have to suit

them

.

One night, as we were getting ready for bed, I was recounting highlights from my day's habit research to Jamie. He'd had a tough day at work and looked weary and preoccupied, but suddenly he started laughing.

“What?” I asked.

“With your books about happiness, you were trying to answer the question âHow do I become happier?' And this habits book is âNo,

seriously

, how do I become happier?'Â ”

“You're right!” I replied. It was really true. “So many people tell me, âI know what would make me happier, but I can't make myself do what it takes.' Habits are the solution.”

When we change our habits, we change our lives. We can use

decision making

to choose the habits we want to form, we can use

willpower

to get the habit started; thenâand this is the best partâwe can allow the extraordinary power of habit to take over. We take our hands off the wheel of decision, our foot off the gas of willpower, and rely on the cruise control of habits.

That's the promise of habit.

For a happy life, it's important to cultivate an atmosphere of growthâthe sense that we're learning new things, getting stronger, forging new relationships, making things better, helping other people. Habits have a tremendous role to play in creating an atmosphere of growth, because they help us make consistent, reliable progress.

Perfection may be an impossible goal, but habits help us to do better. Making headway toward a good habit, doing

better than before

, saves us from facing the end of another year with the mournful wish, once again, that we'd done things differently.

Habit is notoriousâand rightly soâfor its ability to control our actions, even against our will. By mindfully choosing our habits, we harness the power of mindlessness as a sweeping force for serenity, energy, and growth.

Better than before! It's what we all want.

T

o shape our habits successfully, we must know ourselves. We can't presume that if a habit-formation strategy works for one person, it will work just as well for anyone else, because

people are very different from each other

. This section covers two strategies that allow us to identify important aspects of our habit nature: the Four Tendencies and Distinctions. These observational strategies don't require that we change what we're doing, only that we learn to see ourselves accurately.

The Four Tendencies

It is only when you meet someone of a different culture from yourself that you begin to realise what your own beliefs really are.

âGeorge Orwell,

The Road to Wigan Pier

I

knew exactly where my extended investigation of habits would begin.

For years, I've kept a list of my “Secrets of Adulthood,” which are the lessons I've learned with time and experience. Some are serious, such as “Just because something is fun for someone else doesn't mean it's fun for me,” and some are goofy, such as “Food tastes better when I eat with my hands.” One of my most important Secrets of Adulthood, however, is: “I'm more like other people, and less like other people, than I suppose.” While I'm not much different from other people, those differences are

very important

.

For this reason, the same habit strategies don't work for everyone. If we know ourselves, we're able to manage ourselves better, and if we're trying to work with others, it helps to understand

them

.

So I would start with self-knowledge, by identifying how my nature affects my habits. Figuring that out, however, isn't easy. As novelist John Updike observed,

“Surprisingly few clues are ever offered

us as to what kind of people we are.”

In my research, I'd looked for a good framework to explain differences in how people respond to habits, but to my surprise, none existed. Was I the only one who wondered why some people adopt habits much more, or less, readily than other people? Or why some people dread habits? Or why some people are able to keep certain habits, in certain situations, but not others?

I couldn't figure out the patternâthen one afternoon,

eureka.

The answer didn't emerge from my library research, but from my preoccupation with the question my friend had asked me. I'd been pondering, yet again, her simple observation: she'd never missed practice for her high school track team, but she can't make herself go running now. Why?

As my idea hit, I felt the same excitement that Archimedes must have felt when he stepped into his bath. Suddenly I grasped it. The first and most important habits question is:

“How does a person respond to an expectation

?” When we try to form a new habit, we set an expectation for ourselves. Therefore,

it's crucial to understand how we respond to expectations

.

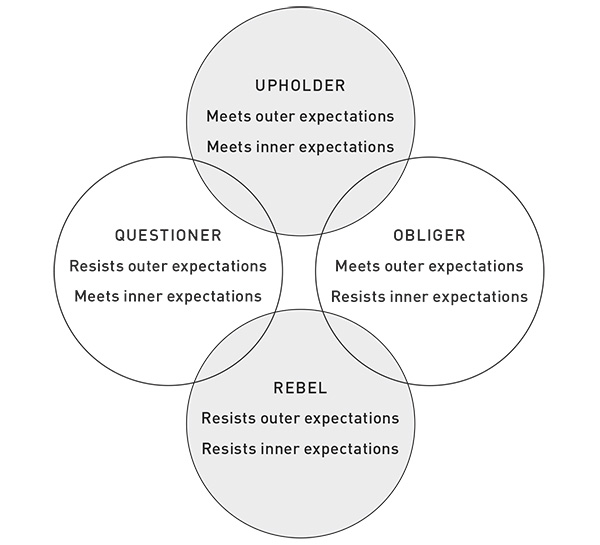

We face two kinds of expectations:

outer expectations

(meet work deadlines, observe traffic regulations) and

inner expectations

(stop napping, keep a New Year's resolution). From my observation, just about everyone falls into one of four distinct groups:

Upholders

respond readily to both outer expectations and inner expectations.

Questioners

question all expectations, and will meet an expectation only if they believe it's justified.

Obligers

respond readily to outer expectations but struggle to meet inner expectations (my friend on the track team).

Rebels

resist all expectations, outer and inner alike.

As I struggled to find a name for this framework, one of my favorite passages, from Sigmund Freud's “The Theme of the Three Caskets,” popped into my head. Freud explains that the names of the three goddesses of fate mean “the accidental within the decrees of destiny,” “the inevitable,” and “the fateful tendencies each one of us brings into the world.”

The

fateful tendencies each one of us brings into the world.

I decided to name my framework the “Four Tendencies.” (The “Four Fateful Tendencies,” though accurate, sounded a little melodramatic.)

As I developed the framework of the Four Tendencies, I truly felt as though I were discovering the Periodic Table of the Elementsâthe elements of character. I wasn't making up a system; I was uncovering a law of nature. Or perhaps I'd created a habits Sorting Hat.

Our Tendency colors the way we see the world and therefore has enormous consequences for our habits. Of course, these are

tendencies,

but I've found, to a degree that surprises me, that most people do fall squarely into one camp, and once I identified the Tendencies, I got a kick from hearing the people within a given Tendency make the same kinds of comments, over and over. Questioners, for example, often remark on how much they hate to wait in line.

Upholders respond readily to outer expectations and inner expectations. They wake up and think: “What's on the schedule and the to-do list for today?” They want to know what's expected of them, and to meet those expectations. They avoid making mistakes or letting people downâ

including themselves

.

Others can rely on Upholders, and Upholders can rely on themselves. They're self-directed and have little trouble meeting commitments, keeping resolutions, or meeting deadlines (they often finish early). They want to understand the rules, and often they search for the rules beyond the rulesâas in the case of art or ethics.

One friend with an Upholder wife told me, “If something is on the schedule, my wife is going to do it. When we were in Thailand, we'd planned to visit a certain temple, and we wentâeven though she got food poisoning the night before and was throwing up on our way there.”

Because Upholders feel a real obligation to meet their expectations for themselves, they have a strong instinct for self-preservation, and this helps protect them from their tendency to meet others' expectations. “I need a lot of time for myself,” an Upholder friend told me, “to exercise, to kick around new ideas for work, to listen to music. If people ask me to do things that interfere, it's easy for me to tell them âno.'Â ”

However, Upholders may struggle in situations where expectations aren't clear or the rules aren't established. They may feel compelled to meet expectations, even ones that seem pointless. They may feel uneasy when they know they're breaking the rules, even unnecessary rules, unless they work out a powerful justification to do so.

This is my Tendency. I'm an Upholder.

My Upholder Tendency sometimes makes me overly concerned with following the rules. Years ago, when I pulled out my laptop to work in a coffee shop, the barista told me, “You can't use a laptop in here.” Now

every time

I go to a new coffee shop, I worry about whether I can use my laptop.

There's a relentless quality to Upholders, too. I'm sure it's tiresome for Jamieâsometimes, it's even tiresome for meâto hear my alarm go off

every

morning at 6:00. I have an Upholder friend who estimates that she skips going to the gym only about six times a year.

“How does your family feel about that?” I asked.

“Well, my husband used to complain. Now he's used to it.”

Although I love being an Upholder, I see its dark side, tooâthe gold star seeking, the hoop jumping, the sometimes mindless rule following.

When I figured out that I was an Upholder, I understood why I'd been drawn to the study of habits. We Upholders find it relatively easy to cultivate habitsâit's not

easy

, but it's easier than for many other peopleâand we embrace them because we find them gratifying. But the fact that even habit-loving Upholders must struggle to foster good habits shows how challenging it is to form habits.

Questioners question all expectations, and they respond to an expectation only if they conclude that it makes sense. They're motivated by reason, logic, and fairness. They wake up and think, “What needs to get done today, and why?” They decide for themselves whether a course of action is a good idea, and they resist doing anything that seems to lack sound purpose. Essentially, they turn all expectations into inner expectations. As one Questioner wrote on my blog: “I refuse to follow arbitrary rules (I jaywalk, as long as there are no cars coming, and I'll go through a red light if it's the middle of the night, and there's no other traffic in sight) but rules that I find based in morality/ethics/reason are

very

compelling.”

A friend said, “Why don't I take my vitamins? My doctor tells me I should, but usually I don't.”

She's a Questioner, so I asked, “Do you believe that you need to take vitamins?”

“Well, no,” she answered, after a pause, “as a matter of fact, I don't.”

“I bet you'd take them if you thought they mattered.”

Questioners resist rules for rules' sake. A reader posted on my blog: “My son's school principal said that kids were expected to tuck in their shirts. When I expressed surprise at this seemingly arbitrary rule, the principal said that the school had many rules just for the sake of teaching children to follow rules. That's a dumb reason to ask anyone, including children, to follow a rule. If we know of such rules we should seek and destroy them, to make the world a better place.”

Because Questioners like to make well-considered decisions and come to their own conclusions, they're very intellectually engaged, and they're often willing to do exhaustive research. If they decide there's sufficient basis for an expectation, they'll follow it; if not, they won't. Another Questioner said, “My wife is annoyed with me, because she really wants us both to track our spending. But we're not in debt, we spend within our means, so I don't think that getting that information is worth the hassle. So I won't do it.”

Questioners resist anything that seems arbitrary; for instance, Questioners often remark, “I can keep a resolution if I think it's important, but I wouldn't make a New Year's resolution, because January first is a meaningless date.”

At times, the Questioner's appetite for information and justification can become overwhelming. “My mother makes me insane,” one reader reported, “because she expects me to need tons of information the way she does. She constantly asks questions that I didn't ask, wouldn't ask, and generally don't think I need to know the answers to.” Questioners themselves sometimes wish they could accept expectations without probing them so relentlessly. A Questioner told me ruefully, “I suffer from analysis paralysis. I always want to have one more piece of information.”

Questioners are motivated by sound reasonsâor at least what

they believe

to be sound reasons. In fact, Questioners can sometimes seem like crackpots, because they may reject expert opinion in favor of their own conclusions. They ignore those who say, “Why do you think you know more about cancer than your doctor?” or “Everyone prepares the report one way, why do you insist on your own crazy format?”

Questioners come in two flavors: some Questioners have an inclination to Uphold, and others have an inclination to Rebel (like being “Virgo with Scorpio rising”). My husband, Jamie, questions everything, but it's not too hard to persuade him to uphold. As an Upholder, I doubt I could be married happily to someone who wasn't an Upholder or a Questioner/Upholder. Which is a sobering thought.

If Questioners believe that a particular habit is worthwhile, they'll stick to itâbut only if they're satisfied about the habit's usefulness.

Obligers meet outer expectations, but struggle to meet inner expectations. They're motivated by

external accountability

; they wake up and think, “What

must

I do today?” Because Obligers excel at meeting external demands and deadlines, and go to great lengths to meet their responsibilities, they make terrific colleagues, family members, and friendsâwhich I know firsthand, because my mother and my sister are both Obligers.

Because Obligers resist inner expectations, it's difficult for them to self-motivateâto work on a PhD thesis, to attend networking events, to get their car serviced. Obligers depend on external accountability, with consequences such as deadlines, late fees, or the fear of letting other people down. One Obliger wrote on my blog, “I don't feel a sense of accountability to my calendar, just to the people associated with the appointments. If the entry is just âgo for a jog' I'm not likely to do it.” Another Obliger summarized: “Promises made to yourself can be broken. It's the promises made to others that should never be broken.” Obligers need external accountability even for activities that they want to do. An Obliger told me, “I never made time to read, so I joined a book group where you're really expected to read the book.” Behavior that Obligers sometimes attribute to

self-sacrifice

â“Why do I always make time for other people's priorities at the expense of my own priorities?”âis often better explained as

need for accountability

.

Obligers find ingenious ways to create external accountability. One Obliger explained, “I wanted to go to basketball games, but I never went. I bought season tickets with my brother, and now I go, because he's annoyed if I don't show.” Another said, “If I want to clean out my closet this weekend, I call a charity now, to come and pick up my donations on Monday.” Another Obliger said, with regret, “I signed up for a photography course, because I knew I needed assignments and deadlines. I took several classes, then thought, âI love it, so I don't need to take a class.' Guess how many photos I've taken since? One.” Next semester, he's taking a class.