Betraying Spinoza (20 page)

Authors: Rebecca Goldstein

Tags: #Philosophy, #General, #Modern, #Biography & Autobiography, #Jewish philosophers, #History, #History & Surveys, #Jewish, #Heretics, #Biography, #Netherlands, #Philosophers

S

pinoza names the ecstasy his system delivers

Amor dei intellectualis

, the intellectual love of God. This love, as its name suggests, is at once a cognitive and an emotional state, and it is the very highest state achievable, whether measured on the scale of cognition or emotional well-being.

It is, first of all, maximally knowledgeable, constituting the third, and highest, level of knowledge,

scientia intuitiva

, or intuitive knowledge. (Below intuitive knowledge lies

ratio

, or scientific knowledge, which involves the explanation of finite things by their necessary connections to their finite causes. Using

ratio

, [configurations of] bodies are derived from other [configurations of] bodies via the mathematically expressed laws of nature. And below scientific knowledge lies imagination, which, for Spinoza, includes all the passively received data of the senses, devoid as they are of any inkling of the necessary connections that constitute reality. For Spinoza, unlike Descartes, the distinction between the imaginative and the veridically perceptual is no consequential distinction at all.) In intuitive knowledge, the highest level of knowledge, each thing is grasped in the context of the infinite explanatory system,

Deus sive natura

, that is, the world, the details of which cannot—precisely because they are infinite—be exhaustibly grasped in their inexhaustible entirety but can nevertheless be holistically intuited. In intuitive knowledge, the whole entailed system—for each implicated thing entails the whole implicative order—is made palpably, if intuitively, present. We can only approach this third level asymptotically. We can never achieve it fully, since to do so would be to possess the mind of God, the thinking with which the infinite order of necessary connections thinks itself.

In addition to being the highest cognitive state, the intellectual love of God is an emotional state (for Spinoza the cognitive and emotional are constantly, necessarily, merged), and, again, it ranks as the highest state possible, this time judged in terms of one’s emotional well-being. This outward absorption of the self into a vision of

Deus sive natura

, being maximally expansive, is also maximally pleasurable. The very activity of explanation, the exhilarating sense of expanding one’s ideas to take in more of the world, and thus the exhilarating sense of one’s own outward expansiveness into the world, is, in itself, a sort of love, only now with the explanation of the world—which is the world—as its object. And the exhilaration is aided and abetted by the sense of firm control, the activity of loving expansiveness not to be cut short by the loved object’s independence of (finite) mind and fickleness of spirit. The painful urgency and insecurity of love are eliminated when it no longer seeks to complete itself in another person but rather in the understanding of God, that is, of the vast infinite system of implications from which we ourselves are implied.

Conatus

, our essence, which dictates that all of our intentions derive from our concerns with our own selves, leads us, if we truly attempt to fulfill ourselves, to see ourselves from the outside, as it were, from the point of view of the infinite system that explains all. True devotion to ourselves will lead us to an objectivity so radical that even our own demise can be contemplated with equanimity. “A free man,” Spinoza tells us in Part IV of

The Ethics

, “thinks of death least of all things; and his wisdom is a meditation not of death but of life.”

One of Spinoza’s uncompleted manuscripts is called

The Treatise on the Emendation of the Understanding

. Its subject is knowledge—what it is and how we acquire it—and Spinoza presumably left off completing it because he realized that his hierarchical theory of knowledge would have to be shown to follow—as all else, for him, follows—from the infinity of necessary connections that is the world.

But the interrupted

Treatise

is of special interest because of its opening paragraph, which is often cited to be the most revealingly autobiographical passage Spinoza ever gave us:

After experience had taught me that all the usual surroundings of social life are vain and futile; seeing that none of the objects of my fears contained in themselves anything either good or bad, except in so far as the mind is affected by them, I finally resolved to inquire whether there might be some real good having power to communicate itself, which would affect the mind singly, to the exclusion of all else; whether, in fact, there might be anything of which the discovery and attainment would enable me to enjoy continuous, supreme, and unending happiness.

This is the only place in his writings where he seems to reveal to us something of the person who stands behind the formidably impersonal system, seeming to share the motive that lay behind its production. Spinoza tells us that he, like all of us, was searching for happiness. He even appears to confess that he had a normal appreciation for the sorts of goods that are commonly supposed to bring us happiness: riches, fame, and sensual pleasure. The problems with the three goods, he discovers, is that they fail to deliver maximum pleasure. They fall far short of yielding continuous, supreme, and unending happiness.

The problem, for example, with sensual pleasure is that, while we desire it, it so enthralls us that it blocks our vision of all other goals, but once the pleasure is sated “it is followed by extreme melancholy, whereby the mind, though not enthralled, is disturbed and dull.”

(This observation raises a question that I will parenthetically raise merely to parenthetically drop, namely, on what was Spinoza’s knowledge of sexual experience based? I think it’s fair to say that none of us has the slightest idea. It could have involved another person—maybe a prostitute? maybe the Clara Marie who might have rejected him for the suitor with the pearl necklace?—or maybe not. Having another person present isn’t required in order to experience that extreme melancholy that follows sexual satiety. The third part of

The Ethics

seems to demonstrate some familiarity with the misery of sexual jealousy: for example, the scholium to Proposition XXXV reads: “He who thinks of a woman whom he loves as giving herself to another will not only feel pain by reason of his own appetite being checked but also, being compelled to associate the image of the object of his love with the sexual parts of his rival, he feels disgust for her.” However, since this is a deductive system, this scholium, like any other proposition in

The Ethics

, might in principle have been inferred a priori, with no experience necessary.)

Then, too, if this sensual pleasure involves another person it exposes one to the problems that likewise plague the pursuit of riches and fame, namely making one vulnerable to factors beyond one’s control. “If our hopes are frustrated, we are plunged into the deepest sadness.” Fame has “the further drawback that it compels its votaries to order their lives according to the opinions of their fellow-men.” And we have seen what Spinoza thinks of the opinions of the multitude. Given that these opinions are, according to his theory of knowledge, basically worthless, since their ideas remain on the level of

imagination

, why should the esteem of the many, which is what fame is, constitute a good?

The ecstatic rationalism that Spinoza works out for us in

The Ethics

claims not only to deliver us a world woven out of the very fabric of logic, unlike any that we could perceive by way of our so-called experience of the world, or even by way of our scientific explanations of our experience; it also claims to provide us with an ecstatic experience, the intellectual love of God, unlike any that we could have arrived at in any other way. It is the desire for that continuous, supreme, and unending happiness which Spinoza cites as his motive for his system.

But though this opening paragraph of the unfinished treatise might seem to speak in Spinoza’s most personal voice, the desire for “happiness” to which he confesses is blandly impersonal, a one-size-fits-all motivation for what is the most rigorous project of rationalism in the history of Western thought. The motivation Spinoza was prepared to put to paper was as universal and impersonal as the finished system it supposedly provoked. What he does not tell us—what he cannot tell us—is that his ecstatic rationalism is a solution to a far more particular problem.

It is the problem of Jewish history.

I

f the supposedly most autobiographical passage in Spinoza’s writings—the opening paragraphs of the unfinished

Treatise

—yield precious little of the person behind the system, where then can we find him? Certainly not in the sculpted formalism of

The Ethics

. Here is the View from Nowhere, still and calm, ordered as reality itself is ordered, a matrix of logical entailments, timeless as mathematics and just as impersonal.

T

he

Tractatus Theologico-Politicus

, however, is a slightly different story. Spinoza interrupted his work on

The Ethics

to compose the

Tractatus

, which—as Mrs. Schoenfeld rightly suggested—scholars believe was partly based on the apologia he composed in Spanish immediately after his excommunication. Perhaps that explains the somewhat less guarded tone that pervades it. His anti-clerical denunciations palpably tremble with outrage. Spinoza somehow or other hoped that this work, which argues against the existence of miracles—

So those who have recourse to the will of God when there is something they do not understand are but trifling; this is no more than a ridiculous way of avowing one’s ignorance

5

—and against the special role of the Jews—

Therefore at the present time there is nothing whatsoever that the Jews can arrogate to themselves above other nations

6

—and that the Bible was written by many authors, whose gifts for prophecy resided not

in their more perfect mind, but with a more perfect power of

imaginations,

7

would convince his contemporaries to give him a clean bill of theological health so that he might be allowed to publish his philosophical masterpiece.

8

(There is probably a falsifying optimism that accompanies any ambitious writer’s undertakings. A realistic assessment of the chances that one’s labors will produce the desired response would advise one to give up before beginning.)

The

Tractatus

is far more informal and far less controlled than

The Ethics

, and in it the first-person voice of Spinoza sometimes speaks, as in this passage, which comes after Spinoza has been arguing that the many chronological inconsistencies and repetitions of the Scriptures argue compellingly that they were authored by several writers, not one, and certainly not by Moses, who could not have had access to many of the facts related:

Indeed, I may add that I write nothing here that is not the fruit of lengthy reflection; and although I have been educated from boyhood in the accepted beliefs concerning Scripture, I have felt bound in the end to embrace the views I here express.

I read these words and my imagination is engaged. The sense of his boyhood world, in certain ways quite similar to my girlhood world, rises up in the phrase “I have been educated from boyhood up in the accepted beliefs.” His life unfolds in the words “I have felt bound in the end to embrace the views I here express.” Spinoza would advise me to disengage my imagination, but I think not.

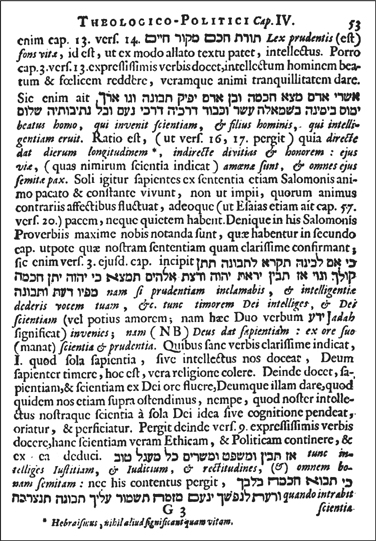

A page from the

Tractatus Theologico-Politicus

To indulge in an imagined sense of his life would count perhaps as one more betrayal of Spinoza. If the personal point of view—that substance of one’s mental life that is the accumulated effects of one’s contingently lived history—are intellectually and ethically negligible, then what value can be placed on a novelist’s attempt to imagine her way into another’s life? Of what redeemable value is such an exercise even when it is his life, Benedictus Spinoza’s, the architect of radical objectivity itself, that one is attempting to inhabit? It is the personal point of view, only once removed, blurring the line between truth and fiction (such blurring is of the essence of the art), mixing the actual thoughts of the philosopher (however conscientiously italicized and marked with endnotes) with mere imaginings.

Spinoza argues that the highest level of reason amounts to a sort of love. I would argue that the highest level of imagination also amounts to a sort of love. I would further argue that the imaginative acts by which we try to grasp the substance of others, that specific singularity of them that resists universalizing into the collective rational im-person, are a necessary component of the moral life. Spinoza, of course, would disagree. Spinoza’s proofs were aimed at inducing only an impersonal love in us,

Amor dei intellectualis

, love for the infinite system that is reality. He does not approve of forsaking philosophy’s proofs, the eyes of the mind, for imaginative sight, no matter how love-infused the sight might be.