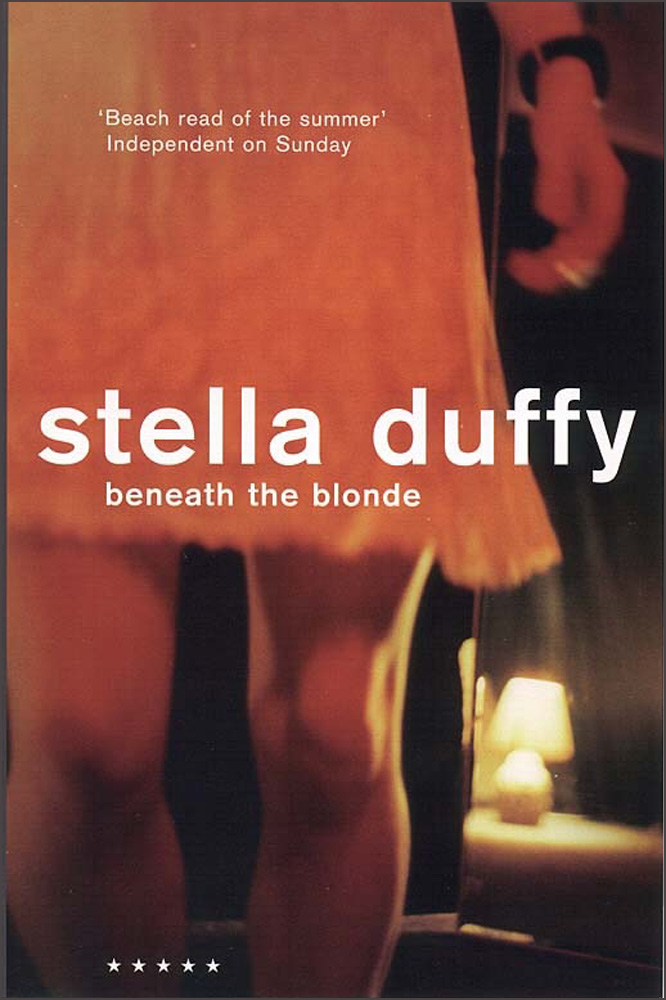

Beneath the Blonde

Read Beneath the Blonde Online

Authors: Stella Duffy

| Beneath the Blonde |

| Saz Martin [3] |

| Stella Duffy |

| Profile Books Ltd (1997) |

Siobhan Forrester, lead singer of Beneath the Blonde, has everything a girl could want - stunning body, great voice, brilliant career, loving boyfriend. Now she has a stalker too. She can cope with the midnight flower deliveries and nasty phone calls, but things really turn sour when intimidation turns to murder.

Saz Martin, hired to seek out the stalker and protect Siobhan, embarks on a whirlwind investigation, travelling with the band from London to New Zealand with plenty of stop-overs. As jobs go, this one shouldn't be too hard, except Siobhan is economic with the truth and Saz isn't sure she wants to keep the relationship strictly business.

Praise for

Beneath the Blonde

“Saz Martin is … an ebullient heroine of courage and wry wit … Duffy’s third novel removes her from the category of ‘promising’ and confirms without doubt that she’s very near the top of the new generation of modern crime writers” Marcel Berlins,

The Times

“Stella Duffy’s writing gets better with each book” Val McDermid,

Manchester Evening News

“Always a pleasure to find a new Stella Duffy novel … a good read and highly recommended”

Diva

Stella Duffy

was born in London and brought up in New Zealand. She has lived in London since her early twenties. She has written thirteen novels, ten plays, and forty-five short stories. She won the 2002 CWA Short Story Dagger for her story Martha Grace, and has twice won Stonewall Writer of the Year in 2008 for The Room of Lost Things and in 2010 for Theodora. In addition to her writing work she is a theatre performer and director. She lives in London with her wife, the writer Shelley Silas.

Stella Duffy

Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 99-63597

A full catalogue record for this book can be obtained from the British Library on request

The right of Stella Duffy to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places and incidents are either the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously.

Copyright © 1997 Stella Duffy

First published in 1997 by Serpent’s Tail 4 Blackstock Mews, London N4 2BT Website:

www.serpentstail.com

First published in this 5-star edition in 2000

Printed in Great Britain by Mackays of Chatham, plc

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3

For my sister Veronica, with love and thanks for all the Marvellous Bumps.

Thanks to Bev Fox and Ian McLaughlin for practical inspiration, location scout Mandy Wheeler, sanity specialists Shelley and Yvonne, and the legal team: Graeme Austin, Claire Bonnet and Steve Harris. Special kihinui to Sandra Morris, kuia-in-waiting and Dave Perese, writer-in-residence.

I would sit in your mother’s kitchen and watch the sun come up. The kitchen is blue. I remember when your dad painted it. He is dead now. They both are. You killed them. Like you killed me. Like you killed everyone in your past. You do not know your mother and you do not know your father and you do not know me. Because that would mean them all knowing who you were. But I remember.

I know enough to conjugate the tense into who you are.

I remember when this was fun, easy. When the long summer holidays were six weeks that seemed like years, punctuated by the melting chocolate peanut slabs at the school pool and the warm Fanta and trips to the beach and the sweltering turkey of a midsummer Christmas afternoon. And it always rained on Christmas afternoon.

And then not many years after that the changes began. The small town grew constricting, the black and white two-channel TV became a symbol of how much you needed to run away, how far we both needed to go. You went further than most.

At eleven you wanted to leave. Told me where you’d go—and why. I didn’t believe it, I called you a liar. We fought, didn’t talk for half a year. By which time our seven-year friendship had faded. You had been leaving me for a long time. You had been leaving everyone. But I never left you.

I helped your dad paint this room. We were almost friends, he and I. Some work together, a beer in the garage. By then it was just postcards from you. They shared them

with me. The scribbled writings from New York, London, Amsterdam, Rio. Your parents shared you with me. Their generosity knows no bounds. That was their choice. I have never chosen to share you with anyone.

Then you killed yourself and the postcards stopped.

And now you say crisps instead of chips and off-licence instead of bottle store and sweets when you really mean lollies. But I know what they’re really called. And I know your name.

You say it was a phoenix reinvention. Say you created yourself new. Recreation. And was it fun? I know all about it. You told your mum and she told me. Neither of us believed it. And anyway, who gave you permission to be reborn? Not me. You’re the Catholic. Resurrection and transubstantiation are foreign words to me. They stick on my tongue like the wafers of dry Jesus you smuggled me one day after Mass. It tasted of nothing.

I’m doing this in memory of you.

A pigeon shat on Saz as she left St Pancras Station. She climbed from the train tired, still slightly hungover from the excesses of the day and within four paces, one of London’s lesser creatures deposited its multi-textured blessing on her front. Her whole front. The tip of her chin, the flare of bare flesh just below her collarbone and the top of her black wool Bloomingdales cardigan. The dark yellow and white crap ran down her left breast and into the top of her bra, leaving an egg yolk stain across her skin. She shifted her old suitcase into the other hand and hurried even faster out to the street, slimy pigeon droppings sliding from her underwired breasts down the ridges of her scarred stomach. Molly hooted from behind a taxi rank and Saz opened the car door, flung the case in the back, herself into the front seat and burst into tears.

Molly said nothing until the sobbing had subsided, just passing Saz a box of tissues and stroking her right leg whenever gear changes allowed. At Camden Lock, a dated blackclad youth holding hands with two baby goth girls skinned his shins on Molly’s new Renault and a drunken old man grinned into the passenger window. Saz finally held back the tears and snot long enough to wind down the window and shout at the pedestrians, “Fuck off, you bunch of complete wankers, this is a road not a fucking shopping mall, use the fucking pedestrian crossing.” The drunk man jumped back in surprise and narrowly missed being run over by a black cab.

When the congestion cleared a little Molly took her eyes off the traffic long enough to look clearly at Saz. She took in the almost dried bird shit in all its glory. “It’s supposed to be lucky, you know.”

Saz snarled, “Being obliged to attend the wedding of your brother-in-law’s homophobic sister and her fascist army husband where the only conversation possible is one in which you tell all present that they’re nasty Tory bigots for whom shooting is too good and then get kicked out of the reception and unceremoniously dumped on the next train home?”

“No. Bird shit is supposed to be lucky.”

“Must be great being a lion in Trafalgar Square.”

“Are you going to tell me what happened or don’t you remember?”

“I remember, I just don’t think I want to. Anyway, it’s your fault, if you’d have been there I wouldn’t have drunk so much.”

“If I’d have been there we’d probably both have been dumped on the next train home and then we’d both be covered in bird shit.”

“It’s still your fault.”

“You knew all along I couldn’t come.”

“Wouldn’t come.”

“I’m not going to argue with you, Saz. I was already committed to working this shift months ago, I’d promised Jim I’d cover for him—for his own wedding I might add—and much as I love your family, there’s no way that my respect for the extended family concept extends all the way out to your brother-in-law’s sister.”

Saz grunted and blew her nose, Molly slowly joined the uphill out-for-dinner traffic in Hampstead High Street.

“And you still haven’t told me what happened.”

“The best man, Jonathan the soldier, is a racist, sexist pig

who didn’t realize I was gay when he started slagging off queers.”

“I guess he didn’t know it was a reclaimed word then either?”

“It’s not reclaimed the way he uses it. Nor are nigger, paki or not—in his mouth—girl.”

“So you had a go at him?”

“No, I should have but I didn’t. I was being ‘good’. I was being the quiet sister.”

“Must have been hard.”

Saz ignored Molly and continued with her description of the day’s events. “I sat quietly listening to his bigoted ranting until Tony had a go at him and then Cassie joined in. I just sat there like an idiot, thinking it was only my family by marital extension and Emily Anne couldn’t help being so stupid and I really shouldn’t interfere and I’d had too much to drink anyway and I was so angry that I’d only talk rubbish—”

“Or burst into tears.”

“Exactly. So I sat there and listened to my brother-in-law and my sister try to reason with him, telling all those pathetic placatory stories, you know—‘Molly’s Asian and she’s wonderful…’”

“All absolutely true.”

“That’s not the point, Moll, and you know it. Anyway, he’s probably the kind of bloke who has one friend in every shade just so he can prove he’s not racist. So finally he turns his attention to me, telling Tony and Cassie, ‘Your sister’s no better, even if she is a dyke she should still have the decency to wear a dress to a formal occasion.’ Tony was about to hit him and so I just stood up, climbed on to the table—by this time we were all sitting at the bridal table itself—and I took off the trousers and the jacket of my beautifully cut and incredibly expensive deep-red raw silk suit to show him and the rest of the assembled guests just

exactly why I wasn’t wearing dinky little mini skirts so often this season.”

Molly pulled the car up outside their flat. “Oh, I see.”

“They certainly did.”

“And then?”

“Then, while no doubt one or two people were enjoying the sight of my Janet Reger underwear, everyone else was gasping in shock at my horrifically scarred legs and stomach.”

“They’re not that bad.”

“Not to you, darling. You love me, you’re used to them. Anyway, you’re a doctor.”

“So what happened next?”

“Well, it got even juicier after that. Tony swiftly hit the bastard best man—causing his nose to bleed copiously all over the chief bridesmaid’s lemon taffeta dress and Cassie retrieved the kids and bundled us all back to the bed and breakfast before the remaining guardsmen took it into their tiny heads to see to Tony. They stayed the night and I got the first train home to you.”

“So you didn’t exactly get kicked out?”

“Not as such. But I’m tired, hungry, hungover, furious with myself for letting him get to me and … oh God, you know. This.”

She hit her right thigh in frustration and Molly took Saz’s scarred hand to stop her hitting herself again.

“Yeah, babe, I know.”

That night Molly lay in bed beside her girlfriend, stroking the heavy lines the burn scars had left on Saz’s stomach and legs. The scars from a job that had gone badly wrong. Scars that, although they were slowly fading, could never be removed completely, either from Saz’s body or her mind. Molly let her hand travel up the thick ridge of burned skin

along Saz’s thigh, gently easing pressure where scar tissue turned to sex tissue. After more than a year of various treatments and painfully slow healing, Saz was almost used to what she referred to as her “branding”, but there were still many times when she reached her hands down her own body and felt disgust, when she looked at her newly mottled body and longed for the smooth single-coloured skin she’d grown up with and had loved to both feel herself and have others discover. Saz’s physical strength and a large dose of body image politics had steered her through much of the pain of healing, but Molly knew that her lover’s defiant, drunken gesture at the wedding would no doubt leave its own scabby residue to pick over in the coming weeks.