Belisarius: The Last Roman General (50 page)

Read Belisarius: The Last Roman General Online

Authors: Ian Hughes

Camping at the village of Chettus, near to the Huns at Melantias, Belisarius had the peasants and civilians dig a large trench around his camp before lighting a large number of campfires to exaggerate the size of his force and sending out spies to keep an eye on Hunnic movements (Agathias,V.15.2–16.4–5). At first the Huns were subdued by the threat, but once they learned of the true composition of Belisarius’ forces they prepared to attack. Zabergan with 2,000 Huns detached himself from the main force and advanced towards Chettus (Agathias, V. 19.3). In the meantime, Belisarius was having trouble with the raw levies. They had become overconfident and were totally unprepared for a real battle. As a result, Belisarius made a speech that sobered the men, leaving them more cautious but still confident in eventual victory (Agathias, V.17.1–11).

Learning from his scouts of Zabergan’s approach, Belisarius deployed his forces. Judging that the Huns’ approach would lead them through a nearby wooded glen, he split his 300 veterans into three groups of 100. Two of these divisions were sent into the woods on either side of the glen, and ordered to wait for a signal from Belisarius before emerging to attack the Huns in the flank and rear. In this way, Belisarius hoped to constrict the enemy within a very tight space, so negating the advantage of their superior numbers. Belisarius remained in the centre with the remaining 100 veterans, and he deployed the untrained men behind him, with orders to shout and make a lot of noise (Agathias. V. 19.4–5).

When the enemy saw Belisarius’ small force they advanced to meet him in the glen. Belisarius led the charge with his men, with the main force of peasants and citizens holding their ground and causing as much noise as they could. He also gave the signal for the troops in the woods to charge into the flanks and rear of the Huns. Agathias relates that the noise and the confusion caused by the swirls of dust created by the peasants was out of all proportion to the size of the battle. The Huns now did exactly what Belisarius had anticipated; they drew together ‘so tightly that they could not defend themselves, since there was no room to use their bows and arrows or to manoeuvre with their horses’. Stunned by the noise and dust, the Huns were finally broken by Belisarius’ frontal assault and, as the peasants and citizens advanced, they fled in disorder. Even now, Belisarius retained control; the pursuit was orderly and did not allow the Huns to regroup and counterattack, since the Byzantines retained their order and so did not present a target vulnerable to such a move. The nature of the attack and their defeat so terrified the Huns that they did not even use the ‘Parthian-shot’ tactic for which they were famous, instead fleeing without any attempt at resistance (Agathias,V.19.7 – 20.1).

Retreating to Melantias, Zabergan immediately broke camp and the Huns withdrew. At the same time, the Huns that had advanced to the Chersonese had started their assaults. However, Germanus the son of Dorotheus defeated their attempts to take the city, even destroying an attempt by the Huns to attack the city from the sea by using small skiffs against their hastily-made armada of reed boats (Agathias. V.22.3–8).

Both groups of defeated Huns now came together under Zabergan, and learned that the assault on Greece had also failed. Yet Zabergan refused to leave Byzantine territory without something to show for his efforts, so he ransomed the captives they had previously taken before returning to their homes north of the Danube.

According to Agathias, the episode served to highlight the difference between Justinian and Belisarius: the population of Constantinople lauded Belisarius for saving them in their hour of need and defeating the Huns when heavily outnumbered (V.20.5); they castigated Justinian for his seemingly cowardly action in ransoming the captives and so ‘buying’ peace (V.24.1). Yet Agathias saw further than this, and relates that Justinian now stopped the tribute to a separate group of Huns, led by Sandilch, claiming that the money that was due to them had instead been paid to Zabergan and his horde; if they wanted the money, they needed to get it for themselves. As a consequence, the Huns of Zabergan and Sandilch spent a long time in a war against each other, so leaving the empire free from attack and so weakening the two groups that by Agathias’ time they had fallen under the control of other barbarians and no longer existed as separate entities (V.25. 6).

Belisarius as general

This last battle shows that Belisarius had lost none of his ability to motivate and control his men and ensure that they followed his plans for engagement. Furthermore, the manner of the ambush and the reasoning behind the decision to use it illustrate that he had lost none of his strategic or tactical ability after such a long time taking part in only civilian affairs. As a final observation, his deployment of the large number of civilians and the manner in which they contributed to the battle with only a little risk to their lives show that he had retained his desire to keep casualties amongst his own forces to a minimum. The battle was a model for those who are outnumbered and outclassed by the enemy.

The last acts

Sadly, Belisarius victory was later used against him. Men of rank remained jealous of his abilities and his influence with the emperor and so began a rumour that he was aiming at the throne; as a result, he was not given any recognition for his deeds against the Huns (Agathias, V.20.5-6).

Furthermore, when another group of Huns invaded the Balkans in 562, Belisarius was overlooked for command against them (as noted by Norwich,

Byzantium,

1989, p.261). It is possible that, in this instance, a younger general could be trusted to lead the fight against the Huns: after all, Belisarius was by now aged around 60. Instead of military glory, Belisarius was embroiled in conspiracy. In November of that year a plot against the emperor was uncovered and two of Belisarius’ staff implicated. Under torture, one of the men named his master as conspirator. Belisarius was formally accused in December 562, when Justinian removed his dignities and privileges and began an inquiry. Under house arrest, Belisarius accepted the situation without protest and waited for the judgement of the emperor.

After a full investigation, Belisarius was found not guilty of plotting to kill Justinian and was restored to favour with all of his previous titles in July 563. The later story that Justinian had Belisarius blinded and forced him to sit in the Lausus Palace with a begging bowl is a complete fabrication.

In Italy, Narses was forced to defend the country from two rebellions. The first was in 563, led by Amingus the Frank and Widin the Goth. The rebellion was defeated and both men were killed. The second was in 565, led by Sindual the Herul. Again, the rebellion was defeated and Sindual was captured and hanged. These would be the last consequences of Belisarius’ invasions of which he would have been aware. He died in March 565 aged around 60 years. Antonina survived him, but it is not known when she died. Only eight months later, in November 565, the Emperor Justinian also died. It was the end of an era.

Chapter 14

Conclusion

Epilogue

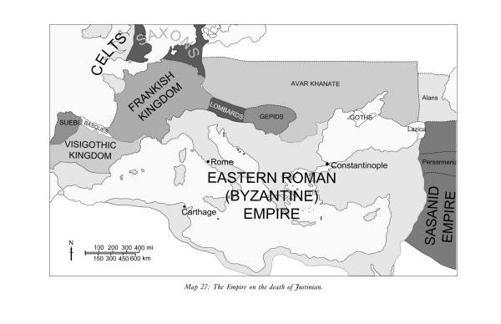

The Byzantine reconquests were not destined to last. In Spain, a revival of Visigothic power gradually reduced the Byzantine possessions until, in the year 631, they were eliminated from the peninsula.

In Italy, events were much more complicated. In 568, only three years after the death of Belisarius, the Lombards invaded Italy, disrupting the province, annexing the north of Italy and establishing the duchies of Benevento and Spoleto in the centre and south. Although control of the remainder remained in Byzantine hands, the long, tortuous border with the Lombards remained a constant threat and siphoned away much needed revenue and manpower. This unsatisfactory arrangement would last until the eleventh century, when the Byzantines were finally expelled from Italy.

The almost-constant warfare on these two fronts would be a drain on the empire when facing its two greatest crises of the seventh century. The first of these was the Persian invasion led by Khusrow II, which, in a series of campaigns over 10 years (607–616), conquered Syria, Armenia, Lazica and Iberia, before culminating in 616 with the capture of Egypt. The Emperor Heraclius was only able to overcome the danger by first forming an alliance with the Khazars (recently established in the Caucasus) and then invading Persia. After the capture of his capital by Heraclius, Khusrow II was deposed by his nobles and a peace agreed that ceded all of the conquered territories back to the Byzantines.

The second crisis came shortly after the Persian War. This was the eruption of Islam. Without warning, a major new military force was unleashed on the world. Within a very short space of time the armies of the Prophet conquered Syria, Egypt, Mesopotamia and Tripolitania from the Byzantines. The Byzantines were lucky: at the Battle of al-Qâdisiyyah in 636 the Sasanids suffered a major defeat at the hands of the Arabic forces. Sasanid Persia came to an end shortly afterwards. As the Byzantines grimly held on in Asia Minor, the Muslims seized the province of Africa in 696, and swept along the North African coast before overrunning Visigothic Spain by 711.

Due to these upheavals, secure control of the western provinces retaken during the reign of Justinian varied considerably. Complete control of Italy lasted for only three years – although partial control of Italy remained for a further 300 years; whilst in Africa the empire continued to reign for a little less than 150 years.

The ultimate loss of the provinces of Spain, Africa and Italy could make all of Justinian’s campaigns seem futile, and it is possible to claim that the manpower used would have been better withheld in reserve and saved against the upcoming Sasanid and Islamic assaults. Yet it should be remembered that Justinian had no warning of the coming crises and that some of the results of the reconquest were both beneficial and long lasting. The province of Africa, along with Sicily and the Balearic Islands, seems to have slowly recovered and been an asset to the empire, contributing taxes and (possibly) manpower whilst being an integral part of the empire’s trading network.

This gives a clue as to what may have been possible had Justinian’s conquests lasted. A fully integrated Italy – including Rome, the major focal point of the earlier imperial trading network – is likely to have seen a slow re-emergence of a more varied trade under imperial sponsorship. It is also possible that Italy itself would have recovered financially and agriculturally from the wars and become a valued member of the provincial system. The consequence of the Lombard invasion was that recovery and integration would not happen. The long border with the Lombards prevented northern Italy from ever being truly stable. This made it impossible to promote either the levels of trade needed by the empire or the agricultural recovery needed to fulfil the potential Italy could have had under sole Byzantine rule. Therefore, Justinian’s conquests might have worked rather than being a drain on imperial resources and could, in the long term, have contributed to the strength and durability of the Empire. We know now that it was not to be, but to suggest that the attempt was futile and a waste because of events Justinian could not have foreseen is inappropriate.

Justinian’s policy

We might now consider how much of Justinian’s western reconquests were a premeditated attempt to restore the ‘Glory of Rome’ and how much was opportunism in the face of events.

In Chapter 6 the causes of the invasion of Africa and the intense diplomatic exchanges needed to give the offensive a chance of success were analysed in detail. The main conclusion that can be drawn from the analysis is that there is little evidence for a long-term plan for imperial recovery. It would appear more likely that the invasion was only considered after the coup of Gelimer, the imprisonment of Hilderic and Gelimer’s refusal to send him to Constantinople. It may be that Gelimer’s refusal to submit to Justinian’s demands, even when threatened with war, forced Justinian’s hand: a failure to act would have undermined his authority, both at home and abroad. As a consequence, it is possible to see the war against the Vandals as a political act made in response to immediate events rather than the calculated act of an emperor determined on a Byzantine revival.