Belisarius: The Last Roman General (29 page)

Read Belisarius: The Last Roman General Online

Authors: Ian Hughes

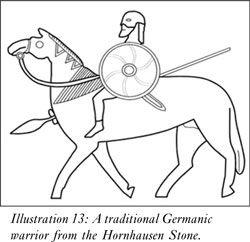

One of these is that held by E A Thompson. In his book,

Early Germanic Warfare

(1982), he claims that the Goths remained armed much as they had in the years before their entry into the Roman Empire. Therefore, they continued to be lightly-armoured horsemen, armed with spear and javelin. He proposes that there had been little change over the previous 2–300 years, but he allows that their entry into the Roman sphere may have allowed them to equip more men as cavalry and to rearm many of their infantry as foot archers.

Unfortunately, much of his argument revolves around the fact that there are few mentions of Goths wearing armour in the sources, it being restricted to named individuals in specific deeds. However, as Boss has noted

(Justinian’s Wars,

1993), the same methodology results in the Romans and Persians being, on the whole, unarmoured, since many of the references to these armies also only state that individuals ‘wear armour’. Yet it cannot be deduced from this that the Roman and Persian rank and file went into battle without body armour.

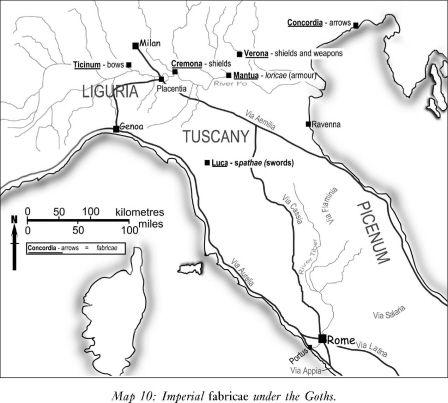

There is a further factor to take into account. When they came into possession of Italy, the Goths inherited some of the

fabricae

listed in the

Notitia Dignitatum,

namely: the

fabrica

at Concordia for making arrows; the one at Verona for making shields and weapons; the one at Mantua for making armour; the one at Cremona for making shields; the one at Ticinum for making bows; and the one at Luca for making swords. It is almost certain that the Goths maintained these

fabricae

and arsenals for their own use, with a consequent upgrade in the number of troops having access to the types of armour previously restricted to the nobility and their immediate followers.

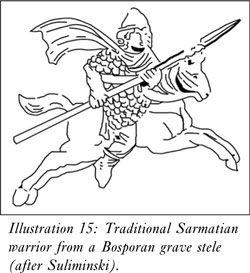

The second theory is outlined by Herwig Wolfram in his book

History of the Goths

(1990). Here, he claims that the Goths’ proximity to the Sarmatians earlier in their history led to their adoption of Sarmatian tactics and equipment.

This ‘sarmaticising’ influence resulted in the Goths using a

kontos

(a heavy lance) two-handed to charge at the enemy rather than using javelins for skirmishing activities.

Supporting evidence can be found in Procopius, where he states that the Goths in Roman service against the Sasanids terrified the Persians ‘with long spears in close array’ (Procopius,

Wars,

II.xviii.24). Although possibly suggesting that the Goths were armed with a lance, the episode concerns the Goths arriving to support a group of fleeing troops. Further, the wording follows classical historical patterns, and may simply be a way of emphasising the cohesion and formation of the Goths as opposed to the disorganisation and lack of formation of the pursuing Persians. It should not, therefore, be used as evidence unsupported.

There is a further distinct problem with the theory. The Sarmatian cavalry had also tended to be equipped with weak bows alongside their

kontos.

It is difficult to accept that the Goths would have adopted the lance used by the Sarmatians without similarly adopting the bow, since the two weapons were an integral part of Sarmatian tactics. Furthermore, there is no mention of Gothic cavalry using bows in Procopius: during the battle of Rome the Goths remained stationary under the storm of Byzantine arrows – hardly likely if they had had the ability to strike back at the enemy, however poorly in comparison to Byzantine practice. Moreover, it would have been difficult to convince the Goths to remain stationary unless they had the additional protection afforded by a large shield, which was not a normal part of the Sarmatian panoply. There is also the categorical statement in Procopius (

Wars,

V.xxvii.15) that the Goths and the Romans were armed completely differently, which would not have been the case had the Gothic cavalry likewise been armed with a bow. Consequently, the interpretation is open to doubt.

As further evidence that the Goths had not changed their methods, Boss (1993, p. 30) uses as confirmation the fact that a fourth-century historian, Ammianus Marcellinus, describes the Quadi as ‘Sarmaticised’ (Ammianus Marcellinus, xvii.12.1) but nowhere claims that the Goths had been similarly influenced. This argument, relying on negative evidence, is by its very nature unreliable and so must be used with extreme caution.

The third theory is that given by Phil Barker in

The Armies and Enemies of Imperial Rome

(1981), in which he claims that the Goths were armed with spear/javelin in continuation of earlier practice, but used the Italian

fabricae

to extend the use of armour to all of the cavalry. There is also the single line in Procopius where Belisarius notes that the Goths had no practice in mounted archery, were only accustomed to fighting with spear and sword, and had no means of defending themselves against mounted archers (Procopius,

Wars,

V.xxvii.27-8). Furthermore, also according to Procopius, Gothic cavalry threw their javelins at Ricilas, one of Belisarius’ guards, as he was scouting, killing him in the process

(Wars,

VII.xi.24). Although, as Boss notes (1993, p.31), the javelin may have been retained either as a secondary weapon or merely have been used by the rear ranks of the cavalry, this is the only attested use of a specific weapon and should, therefore, take precedence over modern theories.

One factor that is not mentioned in the arguments outlined above is that of personal choice. In Chapter 3 it was seen that, even in the ‘regimented’ Roman army, personal choice of equipment had a large part to play. In the Gothic army, choice of weapon would have been an even more unregulated exercise. Therefore, it is likely that some Goths, especially any who had served in the east, may have chosen to change to the

kontus

under the influence of the Persians and of some of the

bucellarii

in the

comitatus

of the Roman generals (see Illustrations 14 and 15). As a consequence, it is reasonable to assume that there was a mixture of weapons and equipment throughout the Gothic army, although, given the literary and pictorial evidence, the use of the shorter spear is likely to have remained the dominant weapon of choice. It should be noted, however, that troops armed with the

kontos

are likely to have been grouped together in ‘specialist’ units, since the

kontus

is a more specialised weapon and its use may not have been suited to such troops fighting alongside spear armed cavalry. It should also be remembered, however, that the sparse nature of the evidence cannot lead us to a definite conclusion concerning the general arming of the Gothic cavalry.

It is also reasonable to claim that the Gothic cavalry wore chainmail armour and either the more traditional patterns of western helmets or possibly new forms of the spangenhelm type produced by the Italian

fabricae.

As a supplement to their traditional spear/javelin and large round shield, they are likely to have carried a Roman-pattern

spatha,

again produced by the Italian

fabricae.

The idea that the Goths maintained production from the Roman

fabricae

is reinforced by the statements in Procopius that the Gothic army was equipped from arsenals controlled by the king

(Wars,

V.xi.28 and V.xvi.ll). In the first of these references, both arms and horses were distributed amongst the troops; in the second, Witigis led horsemen and infantry, ‘the most of them as well as their horses were clad in armour’. Although it is uncertain that the majority of the cavalry had armour on the front of their horses, the fact that this is mentioned by Procopius does suggest that at least some of them were so equipped.

The latter quote also gives us evidence for the nature of the infantry. Barker (1981) suggests that the infantry was composed largely of unarmoured archers, there to give supporting fire to the cavalry. However, Procopius’ wording suggests the majority of the army was armoured, so implying that at least a large proportion of the infantry were heavy spearmen. The latter is reinforced to a degree by Belisarius’ statement to his friends during the siege of Rome that the Goths had no answer to the Byzantine horse archers (Proc V. xxvii. 27). If the Goths had been able to deploy very large numbers of foot archers, Belisarius would not have been able to employ the hit-and-run tactics used during the siege of Rome, as the small numbers of Byzantine cavalry would have been very exposed in the face of the ensuing large volumes of infantry missiles.

In conclusion, it is possible to describe the Gothic army as based largely upon heavily-armoured cavalry using their traditional spears and javelins, with perhaps a few troops armed instead with the longer

kontos.

The infantry appears to have been dominated by heavily armoured spearmen, with an auxiliary force of archers to give supporting fire when needed. This army was very different to the totally-mounted Vandal armed forces, yet, as Belisarius was to quickly ascertain, they shared a major flaw when pitted against the Byzantines.

Belisarius recaptures Rome

Learning of the Byzantine invasion, the new king, Witigis’ took steps to counter the offensive, proceeding to Rome with a large force of Goths and ordering the arrest of Theodegisclus, son of Theodahad. However, he was faced with a dilemma. Belisarius was expected to move north from Naples, but Constantinianus was in a strong position in Illyricum and could easily march into the north of Italy. Furthermore, the Franks were in a threatening position to the northwest of Italy.

Witigis decided to play for time. Leaving a garrison of 4,000 men under Leuderis in Rome, taking many senators as hostage and urging Pope Silverius and the Roman citizens to remain loyal, he moved to Ravenna. The city was strategically placed at the focus of the three possible avenues of attack. From here, he could move to repulse either the Franks or Constantinianus, or he could advance upon Rome should it be threatened by Belisarius.