Belinda's Rings (2 page)

That mother needs to learn a thing or two about discipline, she said.

Oh I know, I said. I shook my head, and so did she. I was surprised how easy it was to play the part. At that moment, I was just some random girl shopping by herself. Another stranger, eyeing that bad mother's abandoned shopping cart with the gummy bears and Chef Boyardee and cheap bologna.

It boggles the mind, she said. I held her coat by the shoulder-pads as Grape Nuts lady swiped at it with balled-up napkins. I wondered what âit' was exactly that boggled the mind â Squid or Mum.

What did you feed him, Grace? Mum asked me when we got to the van. She smeared a baby wipe between Squid's fingers, bunching and folding.

I don't know, I said. Cheerios. One of those cans of creamed corn?

The Heinz ones? Mum asked, huffing out one of her it's-all-your-fault sighs. You know the Heinz ones give him diarrhea.

I thought it was just the beans ones that made him do that, I said. Besides, it's not my fault. He's a baby, last time I checked.

Mum plonked Squid into his car seat and buckled him in, didn't bother to readjust his scrunched-up hood behind his neck. I climbed in next to him, pulled his hood out from under the seatbelt. Mum heaved the door shut so hard the whole van shuddered, like she always told me never to do.

It was the first time I knew â really knew â I was alone. Me, separate from Squid and Mum. Mum drove home like a zombie, arms limp and back hunched. Even from the back seat of the van I could tell she was making movements she'd memorized from driving this route again and again, week after week. The sound of the brakes at the stop sign, the rhythm of the engine, the timing of the turn signal, left here, then right there, familiar as a song that gets overplayed on the radio. I watched a few raindrops river down the window and imagined us underwater, all separate, in our own little bathyspheres, roving around the deep ocean. We were trapped inside, looking for the same route to the surface.

Back then, Squid was going through a vegetarian phase. If we tried to hide a little morsel of sliced ham in his mashed-up squash, he'd just suck off all the squash and eject the cleaned ham chunk neatly like a tiny VHS tape.

The funny thing is that squid â the giant kind, with eyes the size of dinner plates â are carnivorous. When I first read that in one of Wiley's

National Geographic

s â

giant squid have eyes the size of

dinner plates

â I imagined being eaten by a squid. I don't know why. Maybe it was the mention of âdinner.' But I imagined the tentacles shooting out, all of them at once, and cinching around me, wrapping around and around. And for some reason I wasn't wearing any clothes, so I could feel the slimy tentacles slithering all over my body. I felt the suction cups sucking great big purple rings into the skin of my arms and legs, my naked back. My cheek squishing into an enormous black eye, my mouth filling with jelly flesh. I imagined it like a great big squiddy hug, except the squid squeezed so tight that my ribs broke and my lungs burst like balloons.

I found out later, when I really got into marine biology, that it wouldn't happen that way. Squid actually only use two of their tentacles â the two longest ones, shaped like spears at the ends â to grab their prey. The other eight tentacles are really just for show. It's only because they look so different from us â foreign, like they belong to another world â that we find them so threatening. It's like that old saying goes: we fear what we don't understand.

THE MAN SITTING NEXT

to her on the plane was dressed in a suit.

Idiot, Belinda thought. Only an idiot would wear a suit on a nine-hour flight. Belinda had worn her pajama pants and an old t-shirt, but she still felt restless after the first hour. She'd taken her shoes off and wrapped her feet in a blanket. She'd tried curling up in a ball and taking a nap, but her feet kept slipping off the seat. Every few minutes she'd feel her back slumping, her bum creeping to the edge of her seat, and would promptly shimmy herself upright. It had been so long since she'd flown; Belinda wondered if this discomfort was an indication of her aging body. But the man next to her hadn't moved. He had his headphones on, and he'd been staring blankly at the headrest in front of him.

Belinda wondered if perhaps the man was crazy. She'd recently learned that there were a lot of crazy people in the world, and many of them could mask it very well. Belinda herself had even married one. Several of the mental disorders she'd been reading up on sounded just like people she knew. She was convinced that one of her coworkers, Sabrina, had Histrionic Personality Disorder. In fact, Sabrina's ploys to get attention were almost sociopathic. She'd once stolen a cupcake from the supermarket at the mall, and when the security guards caught her she told the manager some sob story about being so poor she was starving. Later that week, Belinda had seen Sabrina sitting on a restaurant patio downtown, drinking martinis with a strange man. She had met Sabrina's husband before and it definitely wasn't him. Sabrina saw her walking by, but she didn't smile or wave or pretend not to notice. Her eyes followed Belinda down the street as if to say, I'm glad you saw me, I hope you tell. That kind of behaviour wasn't normal.

She thought that the man next to her might have Obsessive Compulsive Disorder. That would explain the suit and the rigid posture. It seemed to her that OCD had been running rampant in the last couple of years. The effect of a reactionary society on impressionable minds.

He glanced over when Belinda took out her magazine. It was the latest issue of

The Circular Review

. Belinda got a subscription for the eyewitness accounts. The first issue she received in the mail included one from an English woman named Velta Parr, who claimed to have witnessed a crop circle in the making. The account was written with such elegance that Belinda felt she could hear Velta's voice through the pages, the story thrumming like a melody. She still remembered the details: Velta had been walking around Bryony Hill with her husband on a humid and still day. It was early in the season and the corn was stiff and light green. The air felt so thick they were having trouble breathing as they walked up the hill, which she noted was highly unusual. All of a sudden the stillness broke with several huge gusts of wind rolling over the fields, turning the corn into a sea of turbulent waves. A pillar of light pierced through the grey sky and shone directly on the cornfield. It was so bright that the field became a mirror of undulating white light. The trees at the edge of the field were leaning, bowing to the ground under the force of the wind, and then a band of mist came charging between them, eddying into a shimmering whirlwind. The wind began to whistle above her head; she could feel its pressure pushing down upon her. Her body was covered in pins and needles and when she turned to her husband his hair was standing on end like the bristles of a broom.The grain stalks around them were bending into smooth arcs as the wind raked over them. Under their feet, a spiral began to grow out of the field, beginning in the centre and whorling outwards. It took only a matter of seconds to form, and then the gust swept off into the distance, leaving miniature whirlwinds in its wake. Velta and her husband watched the small whirlwinds comb the grains into pristine concentric circles for several minutes. By the time the winds had dissipated and died off, the sun had almost set. At dusk they returned home, silent and enraptured by their strange encounter.

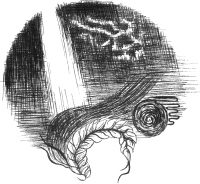

The words flowed through Belinda like scripture. But it wasn't only the words she remembered. Velta had included four illustrations drawn with hundreds of thin, delicate ink lines layered on top of each other. It amazed Belinda that the drawings looked realistic and three-dimensional, and yet when she examined them closely, all she could see were haphazard lines like stray horsehairs. Up close the drawings appeared wild and spontaneous, but the picture in its entirety was most definitely exact and intentional. The vigourous precision infused in each scratchy line told Belinda that this account was the real thing. No person could put herself into a drawing with that level of intensity if she didn't truly believe in it.

Belinda decided to take a painting class after admiring Velta's drawings. Painting seemed easier than drawing; painters could get away with splashing colour all over a canvas and calling it a masterpiece. But she wanted to represent her own encounter with the same careful passion as Velta, and she always felt that her words were insufficient. For the first time in her life, she felt that she had something profound to express.

In the first few classes they had to learn about colour theory. They did a paint-by-number colour wheel with acrylics, and the students, all Belinda's age or older, struggled to keep their brushes from crossing the laser-jet-printer lines. Belinda managed to mix a perfect orange, which her teacher told her was fit for a pumpkin. But when it came to painting actual pictures, Belinda might as well have been a three-year-old with finger paint. Every form she tried to render â a house, a tree, a sky â ended up looking disproportioned and flat, cartoonish. And she didn't want to bother taking the time to mix her own tints, so she laid down blobs of bright red, blue, and yellow and swished them around the canvas. She painted a few scattered circles and squares to practice controlling her shaky lines. Abstract, she called it.

Her teacher stood at her easel and cocked his head to the side as if there were actually a recognizable form embedded somewhere in her painting.

Kandinsky, he announced. Your style is reminiscent of Kandinsky. You should look him up.

Belinda had never heard of Kandinsky but was flattered anyway. After class she went to the library and asked the librarian if she'd heard of Kandinsky, the painter.

Ah yes, the librarian said. Kandinsky, first name Va-silly. He's very famous â you've probably seen his paintings.

Concentric Circles?

Excuse me? Belinda sputtered. She'd never encountered this librarian before. This librarian could not have known that she had seven books on crop circles and other unexplained phenomena checked out from the library.

Here, the librarian said, I'll find the call number for you.

WASSILY KANDINSKY, the cover said. Beneath the text was a picture of a painting: a grid of twelve circles made up of rings in rainbow colours. The inside jacket named the painting

Squares with Concentric Circles.

Wiley had said, Huh, how 'bout that, when Belinda told him about the coincidence. He said the painting looked like a kid had done it.

That's beside the point, Belinda said.

Oh, he said. So what's the point? Wiley was never quite on the same level. But then most men weren't.

WHEN SQUID STARTED SCHOOL

, Mum said it wasn't a proper name to be calling him anymore. But I don't care, I still call him it, even though Jess nags me,

all the kids are gonna make

fun of him

. All the kids make fun of him anyway, and besides, Mum cheated when she named him, just stole the name Sebastian from her sister. I have a cousin back in England named Sebastian, who's older than me. Older than Jess, even.

It doesn't

matter,

Mum said when I reminded her, rolling her eyes.

But what if Auntie Prim comes to visit, I asked.

Oh for Chrissakes, Grace, she won't, was all Mum said. I could tell by the way she tried to shut me up so quick that Wiley didn't know about the cousin. But Wiley didn't seem to care about names, anyway. All he cared about was that his firstborn child inherited his long piano-player fingers.

Unlike Mum and Wiley, I think names are pretty important. When I get married and change my last name, I figure I might as well change my first name too, while I'm doing all that paperwork. Grace is such a boring, geriatric-sounding name. Mum even admits she wouldn't have called me that if it weren't for Da. He wanted to name me the Chinese word for Grace, and Mum told him she absolutely refused to name me anything that people couldn't pronounce. Lo and behold, I got stuck with Grace. I thought about changing it to something cool and unique like Phoenix, but then I figured it'd be hard to get used to being called something so different. So I decided to make just a little change. Gray. Yep. Scratch the âc-e' and add a ây.' I think it fits 'cause it could be for a boy or a girl, and I used to be kind of a tomboy. Also, the sea looks gray when you swim in it. The gray sea â sounds like something from a poem.