BELGRADE (38 page)

Authors: David Norris

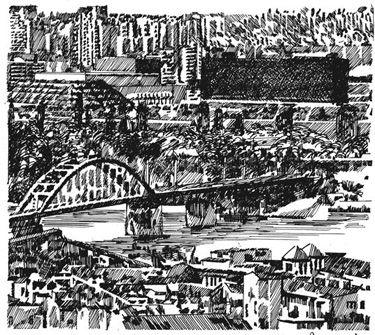

This part of Belgrade has many different faces. What was intended to be the new Yugoslavia’s representation of a collective utopia has become for many a wasteland of sub-standard housing that cannot cope with the pressures put on it in the years since the Second World War. The population of Belgrade has grown beyond all original expectations, and this part of town has become a vast dormitory district whose inhabitants commute each day to work over the Sava, return home from work and go again to the old town for entertainment in the evening. The bridges cannot handle the volume of traffic and they have become notorious bottlenecks. At the same time, New Belgrade contains examples of strikingly modern architectural design and in recent years some parts have become desirable residential addresses. Older buildings have been renovated and some demolished to make way for more solid constructions, especially in the area around the recent Belgrade Arena. These developments are on the road linking the old town with the airport, convenient for today’s business community and close to the new business park developed in the vicinity. Well-heeled incomers are hence providing a stimulus for change, which has led to the first hypermarkets opening in this part of town.

New Belgrade is experiencing a renaissance, but not in the direction that Macura and his colleagues intended in the post-war period, not least because the expectations of the people of Belgrade in the twenty-first century have moved on significantly from those of 1945.

OPULAR

M

USIC AND

Y

OUTH

C

ULTURE

As capital of socialist Yugoslavia, Belgrade was regarded as a Mecca for young people from Eastern Europe who wanted to taste the fruits of the decadent West. It was much easier to travel from Poland, Czechoslovakia and Hungary to Yugoslavia than to capitalist countries. The authorities in other countries with communist governments regarded Yugoslavia with suspicion. It was a mono-party state like them, but with some undesirable features—one of which was a vibrant youth culture. Youth movements representing different fashions in clothes and music such as rockers, hippies and later punks walked the streets, created their rebellious anthems and gathered in their favourite haunts like nowhere else in Eastern Europe.

The regime considered that a policy towards the arts in general that tolerated diversity would be more astute than repression, as Sabrina Ramet remarks in her book

Balkan Babel

: “Hence, although almost from the beginning the party’s cultural commissars were sensitive to rock’s potential for stirring rebellious sentiments, they opted for cooptation rather than repression. Astutely, they made it worthwhile for rock musicians to cooperate. The result was a pronounced sycophantic streak in Yugoslav rock beginning at an early stage.”

Ramet offers an early example of such sycophancy: “The group

Indeksi

, for example—prominent in the mid–1960s—penned a song ‘Yugoslavia,’ which included the lines, ‘We knew that the sun was shining on us, because we have Tito for our marshal!’” Other examples include the veteran Đorđe Balašević’s songs “Count on us” (1978) and “Three Times I saw Tito” (1981), although he has not performed them since the break-up of Yugoslavia.

Teenagers had more of an opportunity to be who they wanted, choose a style of make-up and stand out from the crowd. Uniformity was not enforced on a population wanting to experiment and produce something as a mark of their generation. Belgrade had its own bands and music which really came to the fore in the late 1970s and early 1980s. Writing of this period in his book

The Culture of Power in Serbia

, Eric Gordy comments,

Increasingly open to the West since the middle 1960s and still relatively prosperous, Belgrade youth generated a rock and roll culture that, at least in the minds of local fans, was on a par with the pop scenes of Western Europe. In 1981, the British music magazine

New Musical Express

listed the Belgrade art students’ club

Akademija

as one of the finest music clubs in Europe. It also rated Belgrade’s punk-pop group

Električni orgazam

as one of the finest bands in Europe.

Gordy captures more of the atmosphere of those years and the increasingly critical stance of musicians and singers when he turns to another group founded at the end of the 1970s, Riblja čorba, and its founder Bora Đorđević. He writes of them:

Bora Đorđević achieved tremendous popularity with the band

Riblja čorba

(literally, Fish chowder, although the name also contains an implicit obscene connotation) in the first several years of the band’s existence, mostly through his comic songs, which were principally about his own drunkenness and oafishness. At the same time, several of

Riblja čorba

’s early songs became anthems of anti-Communist rebelliousness.”

Their song “I Won’t Live in Block 65” is about the reality of life in New Belgrade, while “Member of the Mafia” is a thinly veiled attack on the communists: “What’s a piece of paper to me, where it’s written that I’m a member of the mafia.”

One of the influential bands from that time was Partibrejkers, who are still performing over 25 years later. They have an official website now where their music is described in the following terms:

Musically they are some kind of punk version of early 70s Stones style. Blues or better rhythm and blues influences are very strong. There are a lot of bands in ex-Yugoslav countries who sing that way. Try to imagine The Rolling Stones from the early 70s playing punk. It’s not exactly the sound that the New York Dolls had—it’s rawer and faster and more bluesy.

The bands and their fans were Yugoslavs and international in their orientation, so it is no surprise that most of them reacted against the chauvinist euphoria of the late 1980s. There were some notable exceptions, such as Bora Đorđević, who gave their services to nationalist regimes. On the Partibrejkers’ website one of their fans refers to this period, “But there was big shit going on in Yugoslavia. Garage punk was in some way our protest against nationalistic politics.” Bands from Belgrade, Zagreb, Sarajevo, Ljubljana and other major towns travelled and performed to large crowds in all parts of the country. They began touring again as soon as hostilities were over and it was possible to travel. The reception given to groups from other towns, now capital cities of different countries, shows no sign of animosity or hostility. If young people like the music it seems unimportant where the performers come from or if they speak in a slightly different dialect. Perhaps the indifference of youth to playing the card of identity politics produced an ambiguous and dangerous passivity during the wars in former Yugoslavia, but it may now be one of the most positive factors in bringing about reconciliation.

The 1990s saw the rise of a neo-folk brand of music known as “turbofolk”, which combined the oriental rhythms of traditional folk music with a strong disco beat. Intended to appeal to young people, it evoked nostalgia for a false past of national heroics and the simple virtues of a patriarchal code, while promising the contradictory shallow rewards of success today with fast cars and money. On the surface it offered an authentic Serbian alternative to the decadent internationalism of rock and roll.

Belgrade became divided as loyalties in populist politics and popular music cut across each other. Turbofolk in Serbia was associated by default with village life and rural identities, but it slid into Belgrade via the social phenomenon of the urban peasant. The population of the city increased fast after the war from about 400,000 in 1951 to just over 1,400,000 in 1981, with newcomers arriving from the villages and small towns around Yugoslavia. Many families retained strong ties with their original homes fostering a ready environment in which to receive the electronic neo-folk melodies accompanied by kitsch parades of glamorous girls. The music was despised by those who preferred the anarchic defiance of punk or rock and roll. But the internationalist side was rapidly marginalized.

The market for popular music was relatively small and fairly easily controlled, a topic that Gordy discusses in some depth:

Visibly staking out a cultural position that carries clear political implications—for urban culture, for the decadence of the West, against folk nostalgia and nationalism—Belgrade rock and roll narrowed its own cultural space. As the scene took its cultural importance and cultural mission seriously, the borders of the rock and roll genre hardened. With production and distribution of recordings nearly impossible and press runs down to a minimum, media access also minimal, and only a few performance venues, most of them small, commercial success in rock and roll was out of the question.

Pop music was caught up in the nationalist policies of the Milošević government. It has also proven to be one of the factors that connect people from all over the cultural space of former Yugoslavia. The Serbian entry won the 2007 Eurovision song contest largely because of votes from neighbouring countries recently at war. Plans are to host the 2008 competition in the Arena building in New Belgrade.

OOTBALL AND

N

ATIONALISM

Belgrade has many sporting venues and has hosted a variety of international events. At the beginning of the Second World War King Peter sponsored the Belgrade Grand Prix held on 3 September 1939. It was won by the famous Italian driver Tazio Nuvolari. The race had the dubious distinction of taking place just two days after Germany invaded Poland and was the only Grand Prix to be staged during the war. It was watched by some 100,000 spectators, almost a quarter of the city’s population at the time. There has been no Belgrade Grand Prix since then as the communists considered the sport a bourgeois amusement.

In Velmar-Janković’s novel

Dungeon

the narrator, Milica Pavlović, compares the number of those watching the race with those, like her, attending the opening of an exhibition by the painter Sava Šumanović:

There were two main events. The more important one, judging by the number of spectators, was the international automobile and motorbike race round Kalemegdan Park; the lesser one, attracting a small attendance, was the opening of the exhibition of Sava Šumanović, in the New University building, on Prince’s Square. (If I’m not mistaken, that is now the Philological Faculty building, on Students’ Square.) Thirtythree racing cars were to take part in the race, six international aces of the track led by the famous Nuvolari (at least I think that’s what that Italian was called: I didn’t read the headlines referring to the international motor car races again) and 66 motorbikes; after a gap of eleven years, Sava Šumanović was exhibiting more than 400 oils, watercolours, drawings, sketches in the seven large rooms of the New University.

Since the second half of the twentieth century other sports have been more popular than motor racing in Belgrade: basketball, water polo and football. The national teams for Yugoslavia and later Serbia have been very successful in the first two disciplines. In basketball the Yugoslav team took the gold medal at the 1980 Olympic Games. They have been world champions five times, three as socialist Yugoslavia and twice as the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia in 1998 and 2001, and have won gold eight times in the European Championships, most recently in 1995, 1997 and 2001. Some Serbian players have moved to the United States and had very successful playing careers there including Vlade Divac and Predrag Stojaković.

The national water polo team has also enjoyed international success taking in total eight Olympic medals; three gold, four silver and one bronze. Only Hungary has won more medals in this sport. The team beat the USSR in the final of the 1968 Olympics, then in 1984 and 1988 beat the United States. The Partizan Water Polo Club has been European champions six times, most recently in 2006, and once took the Super Champions cup. Games are watched with great passion and a win at international level is generally followed by a cavalcade of cars through the city centre, with horns blaring, drivers and passengers cheering and waving scarves from windows.

The main football clubs in Belgrade are Partizan and Red Star (Crvena zvezda), although they are more correctly names of sporting associations covering a number of disciplines. Red Star was founded on 4 March 1945 and played its first match that day against a team from one of the Partisan battalions. Its second game was held a week later against some British soldiers serving with the military mission. Red Star won. In 1958 they played in the final of the European Cup. Their opponents were Manchester United who flew to Belgrade to play in Red Star’s stadium. The result was a 3–3 draw, but Manchester won the tie 5–4 on aggregate. Their departure was delayed because one of the United players, Johnny Berry, could not find his passport. Their plane stopped for refuelling at Munich as scheduled, but on take-off there was an accident and the plane crashed with many dead and injured. Eight United players were amongst the fatalities resulting from the tragedy. Red Star is the only Serbian club to have won a UEFA competition, taking the European Cup in 1991 against Marseille in Bari. The same year they won the Intercontinental Cup in Tokyo.