Beggars of Life

Authors: Jim Tully

Beggars of Life

Jim Tully, 1886â1947

by Jim Tully

Edited by Paul J. Bauer and

Mark Dawidziak

Black Squirrel Books

KENT, OHIO

© 2010 by The Kent State University Press, Kent, Ohio 44242

All rights reserved.

Library of Congress Catalog Card Number 2010008637

ISBN 978-1-60635-000-3

Manufactured in the United States of America

First published by Albert & Charles Boni, Inc., New York 1924.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Tully, Jim.

Beggars of life / by Jim Tully.

p. cm.

“Edited by Paul J. Bauer and Mark Dawidziak.”

ISBN 978-1-60635-000-3 (pbk. :alk. paper) â

1. Tully, Jim.

2. TrampsâUnited StatesâBiography. I.Title.

HV4505.T8 2010

305.5â²68âdc22

[B]

2010008637

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication data are available.

To

RUPERT HUGHES

A Friend

and

CHARLIE CHAPLIN

A Mighty Vagabond

TRAVEL

The railroad track is miles away,

And the day is loud with voices speaking,

Yet there isn't a train goes by all day

But I hear its whistle shrieking.

All night there isn't a train goes by,

Though the night is still for sleep and dreaming,

But I see its cinders red on the sky,

And I hear its engine steaming.

My heart is warm with the friends I make,

And better friends I'll not be knowing,

Yet there isn't a train I wouldn't take,

No matter where it's going.

âE

DNA

S

T

. V

INCENT

M

ILLAY

PAUL J. BAUER AND MARK DAWIDZIAK

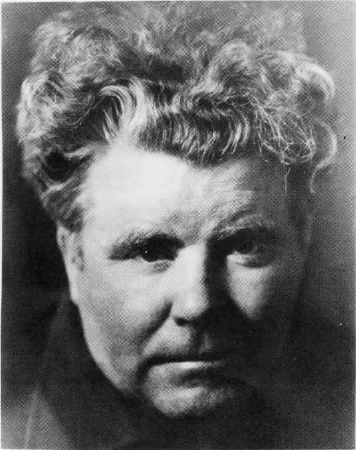

Jim Tully (June 3, 1886âJune 22, 1947) was an American writer who won critical acclaim and commercial success in the 1920s and '30s. His rags-to-riches career may qualify him as the greatest long shot in American literature. Born near St. Marys, Ohio, to an Irish immigrant ditch-digger and his wife, Tully enjoyed a relatively happy but impoverished childhood until the death of his mother in 1892. Unable to care for him, his father sent him to an orphanage in Cincinnati. He remained there for six lonely and miserable years. What further education he acquired came in the hobo camps, boxcars, railroad yards, and public libraries scattered across the country. Finally, weary of the road, he arrived in Kent, Ohio, where he worked as a chainmaker, professional boxer, and tree surgeon. He also began to write, mostly poetry, which was published in the area newspapers.

Tully moved to Hollywood in 1912, when he began writing in earnest. His literary career took two distinct paths. He became one of the first reporters to cover Hollywood. As a freelancer, he was not constrained by the studios and wrote about Hollywood celebrities (including Charlie Chaplin, for whom he had worked) in ways that they did not always find agreeable. For these pieces, rather tame by current standards, he became known as the most-feared man in Hollywoodâa title he relished. Less lucrative, but closer to his heart, were the books he wrote about his life on the road and the American underclass. He also wrote an affectionate memoir of his childhood with his extended Irish family, as well as novels on prostitution, boxing, and Hollywood and a travel book. While some of the more graphic books ran afoul of the censors, they were also embraced by critics, including H. L. Mencken, George Jean Nathan, and Rupert Hughes. Tully, Hughes wrote, “has fathered the school of hard-boiled writing so zealously cultivated by Ernest Hemingway and lesser luminaries.”

With the publication of

Beggars of Life

in 1924, Jim Tully found his voice as a writer. It was a voice that carried the echoes of many sounds: the hum of the railroad lines, the rumble of boxcars, the roar of the chain factories. The voice that had sometimes wavered in his first book, the autobiographical novel

Emmett Lawler

(1922), reached full-throated expression in

Beggars of Life

.

Pounding out the first draft over a six-week span in 1922, Tully poured what he had learned about the road and about life into the book's thirty-one lean chapters. The white-heat of creation had taken his writing to a dynamic new level. Something stronger, harder, and tougher had been forged. Seared away were the weaker elements of his writing so evident in

Emmett Lawler

. Discarded, too, was popular novelist Harold Bell Wright's foolish advice to never write in the first person. Accordingly, Tully had written

Emmett

in the third person, but

Beggars

was Jim Tully's story, written in his own crisp voice. So the descriptions are less sentimental, even though, as the writer himself observed, there are moments of high sentiment.

With

Beggars of Life

, subtitled

A Hobo Autobiography

on the front cover by the publisher, Tully learned how to bring his hard-boiled form of writing to the boiling point. Indeed, it's the book that defines his style, setting the pattern for the twelve books that would follow over the next two decades.

Tully never liked the subtitle, considering it inaccurate and misleading. He would take pains in print and in conversation to point out that the book largely detailed his years as a road kid, not a hobo. Few bothered to make the distinction. He did not, it is worth pointing out, object to the publisher labeling the book an autobiography. And when he began writing his memoirs in the late 1930s, he omitted his road years, letting

Beggars of Life

stand as his account of that period.

Jim Tully just wanted to be known as a writer. The success of his second published book put him on a road to fame as “hobo writer Jim Tully.” Wherever he would go for the remaining twenty-three years of his life, this two-word title would follow him. It was the sort of typecasting that haunted so many who found their way to Hollywood.

Still, at least there was finally a measure of celebrity to be enjoyed, and Tully had

Beggars of Life

to thank for it. There had been too many years of struggle not to savor this delightful turn of literary events. He would write better books, but none would become better known or open more doors for him than

Beggars of Life

. Before the decade was out, there would be a Broadway version of

Beggars of Life

(adapted by no less than playwright Maxwell Anderson) and a film version (directed by William “Wild Bill” Wellman). The book would enjoy several printings, editions, and translations.

Published by Albert & Charles Boni in mid-1924 at a price of three dollars,

Beggars of Life

established the writer as a gritty Gorky-like chronicler of America's so-called “underclass.” At the same time that the Princeton-educated F. Scott Fitzgerald was turning out finely polished tales of Jazz Age wealth, the road-wise Tully was using his raw prose to tell readers about those at the other end of the spectrum.

From the opening conversation on a railroad trestle,

Beggars of Life

rattles along like the Fast Flyer Virginia that Jim boards midway through the book. Chapter after chapter in

Beggars of Life

, one finds Tully sharpening the skills that will carry him through the rest of his writing life. And perhaps the most significant advance over

Emmett Lawler

is his ability to vividly describe an individual or scene with a few tersely worded sentences.

His devotion to such authors as Twain and London had taught him the importance of giving the reader a sense of place, and this he does brilliantly, again and again, throughout

Beggars of Life

.

When we meet a hobo or railway detective in

Beggars of Life

, we are convinced that he is the genuine article, not some romanticized refugee from a cheap melodrama. Tully makes you feel the cold and hunger of a bleak winter ride. He makes you hear the train whistle and the sound of a skull cracking under the snap of a blackjack. He makes you see the tramps and the wanderers with a tenuous grip on the lowest rungs of the social ladder.

Beginning with

Beggars of Life

, when Tully wishes to transport the reader to a time and place, he accomplishes the trick with ease. What was it like waiting in the dark for a train? “Great clouds of steam and smoke fell all around us,” he tells us. “A faded yellow moon would now and then shine through the vapor.”

It's typical of the visual sense Tully displays in

Beggars of Life

. A Hollywood cinematographer could do no better.

In two finely crafted paragraphs, he gives us the sights, sounds, and smells of waking up near a hobo jungle:

The sun climbed early over a wood nearby and threw its rays upon our faces. We sat erect and sleepily watched the peaceful scene around us. Some geese were swimming in circles in the middle of the river. A passenger train thundered over the railroad bridge on its way to Chicago. The frogs still croaked along the bank as we left the boat.

We walked away from the railroad tracks for several hundred feet. Smoke curled through the air at the edge of a wood. As we drew near, we smelt the odour of frying meat and boiling coffee.

Tully could move effortlessly from such straightforward detail to scenes that are evocative, even poetic. His recollections of a spring sunset are reminiscent of Twain's deft handling of hues and colors when describing a river sunrise in

Life on the Mississippi

. Tully is standing near a viaduct after being rousted out of a boxcar by an armed train crew:

The sun soon sank, and the sky faded to a dull grey. Then a blood red cloud line appeared along the horizon, and grey clouds, resembling cement castles with turrets, rested upon it. Yellow clouds rolled above the castles, like immense butterflies unable to find a bush upon which to light.

In a short time all turned scarlet, then purple black, then mauve. At last dark shadows crept over the earth, and all colours merged into blue, through which the stars shone.

The influences of Tully's traveling companions, borrowed or pilfered from libraries across the country, are evident throughout

Beggars of Life

.

The wryly matter-of-fact humorous observation, a Dickens specialty, for instance, becomes a Tully weapon of choice in

Beggars of Life

. “She had either been born tired, or become tired soon after birth,” he says of a farm woman. “No woman could have become so tired without years of experience.”

It is Tully's depiction of sudden violence, however, that brings him into his own as a writer. Here he surpasses his literary heroes, and this will be a hallmark of his best books. Nowhere is this more evident than in

chapter 23

and his riveting account of the hobo-jungle battle between Oklahoma Red and another vagabond.

Like the other aspects of hobo life, the violence is not romanticized. It's treated as a natural part of an overall pattern. Tully's approach is sometimes so casual, that it drifts into the grimly humorous.

Before 1925 was a month old, Tully's sophomore book had collected more than its share of rave reviews.

The New York Times

set the tone.

Jim Tully's book is autobiography naked and unashamed. His story is pitiful and brave, tooâthe story of a boy who at 15 knew more of evil and the black pits of human nature than most men know when they die. Nobody can read it and question its truth.â¦

The men and women that Tully knew in his impressionable years must have brutalized him beyond recovery. But there was something too strong and too fine in him for that to happen.

“How this man can write?”

International Book Review

critic R. A. Parker exclaimed. “Words that are like mountain breezes fresh from wild-flower fields. Words that leap, sing, crawl, explode. Always there is a beautiful rhythm.”

“If all men wrote as honestly as Jim Tully,” critic S. Martin wrote in

The Saturday Review of Literature

, “setting forth their goodness and their nastiness equally, with no attempt at exaggerating either, books would be better and fewer.”

And from Mencken's

The American Mercury

: “The best book of its kind I have ever encountered. Thirty-one strange chapters and all of them good.”

Two reviews must have been particularly pleasing. The first appeared courtesy of Nels Anderson, a sociologist whose pioneering work on vagabondage,

The Hobo

, had appeared the previous year.

In his effort to portray hobo life Tully has torn away the veil of mystery and convention thrown about the hobo by Yankee cartoonists and fiction artists ⦠The hobo is brought before us with all his faults and virtuesâ¦.

Besides being a faithful picture of the road,

Beggars of Life

is an excellent display of hobo slang, morals, ethics, and above all, the philosophy of the underworld. In this respect Tully has not been excelled.

Tully must also have been thrilled with the wildly enthusiastic review

Beggars

received back in Kent, Ohio, where the local paper boosted the book as “the most lively and entertaining autobiography written by an American in many years.” Indeed, “if this book is not awarded the Pulitzer Prize for being the best autobiography of the year, then the judges who award this prize are incapable of recognizing good stuff when they see it.” Those in the town who had known Tully as a chainmaker, boxer, and a tree surgeon must have been amused or amazed. The ex-vagabond was making good on his dream of becoming a writer.

Not that all of the reviews were favorable. Glen Mullin, the critic for the

New York Tribune

, led the attack against

Beggars of Life

. “In craftsmanship the book is crude,” he wrote. “The style is marred by mannered processions of short sentences thrown loosely together and constructed on the same plan. This style is particularly irritating in the expository passages. Possessed as he is of power, intelligence and excellent materials, Mr. Tully should have written a better book.”

Across the Atlantic, the

Manchester Guardian

was equally hostile to

Beggars of Life

. The review caught the attention of

Los Angeles Times

writer Henry Carr, who told his readers that the “highly respectable” English newspaper had been shocked by Tully's book, dismissing it “in cold and cutting words.” Carr quoted those words in his regular column, “The Lancer,” which the

Times

ran on page one: “The life of an American hobo appears to consist mainly of stealing rides on goods trains, with a little fisticuffs and area-sneaking to vary it.” Goods trains? Fisticuffs? Area-sneaking? It was all too tempting for the columnist to resist. “Doubtless Mr. Tully's grief and dismay will be tempered,” Carr suggested, “by his scorn for any reviewer who could call an overland fast freight a âgoods train.'”

Tully may have been even more amused by the critic for

Outlook

magazine. “The âraw stuff,' both in incident and conversation,” this reviewer noted, “is presented absolutely raw; which certainly makes for vividness. But is the life, even of the hobo, quite so consistently hideous as we have it here?”

Life had given him the experiences to fill many more books. He'd known for a while what he wanted to write about; now, at last, he knew how to write about it.

One of the more informed reviews arrived from San Quentin. Johnny Backus, a hobo known as the Flying Tramp, was temporarily grounded in the famous prison. The mighty vagabond wrote Tully to say how much he enjoyed

Beggars of Life

, but added that he had once clung to a mail train farther and longer than the “world's record” described in the book. It was the sort of review that must have made an old road kid smile.