Beethoven: Anguish and Triumph (62 page)

Beyond all that, Mozart's letters document a man fascinated with people and their doings, full of arch, catty, earthy observations of parties and musicales and their denizens. That sensitivity to character and behavior flowed into Mozart's operas, along with his innate comic and theatrical instincts that Beethoven did not possess. Beethoven mastered instrumental music quickly because that was where his gifts and his instincts lay. He could shape a gripping dramatic line in a string quartet or a piano sonata, but the pacing and the arc of a story in words and actions onstage were nearly a closed book to him. Likewise, other people, their passions, their lives, their ideals and quirksâalso virtually closed to him.

What is emotionally profound and universal in Beethoven's music is what he observed in himself. He approached opera the same way. In the story of

Leonore

he was interested in ideas, ideals, feelings, not so much in behavior or in characters, though he knew he had to portray those elements and he did, with spotty results. In the first act he resorted to Mozartian conventions of comic opera that hardly suited the story. Still, from the beginning he kept his eye on where the opera's dramatic climax lay and knew what would express it. The whole story would turn on a single transformative moment: a bugle call.

Meanwhile he always had more trouble writing vocal music than instrumental. In a sketchbook for

Leonore

there are eighteen different beginnings to Florestan's aria “In des Lebens Frülingstagen” and ten for the chorus “Wer ein holdes Weib.”

25

From choosing a key to shaping a melody, he struggled with setting words. Partly for just that reason, as with counterpoint, he attacked the problem with implacable determination. When all was done, his commitment to write opera, for reasons both careerist and personal, was one more decision he made and stuck to wherever it took him and whatever it cost him. Like other such decisions in his life, it cost him a great deal.

To translate and adapt the French libretto of

Leonore

, Beethoven recruited a friend he judged to be a reliable collaborator. Joseph von Sonnleithner was a lawyer and son of a lawyer who had also been a composer; this son was a diplomat and music lover interested in composers of the past. He had made a nearly three-year tour of Europe gathering rare old scores for study and publication. Besides his profession as a bureaucrat, Sonnleithner was a founding partner in a music-publishing firm with the anomalous name of Bureau des arts et d'industrie, which published a good deal of older music by J. S. Bach and others, and by 1814, forty-four works by Beethoven.

26

Just as usefully, as he worked with Beethoven customizing the libretto of

Leonore

, Sonnleithner served for several months as artistic director of the Theater an der Wien, after that for ten years as secretary of the court theaters.

27

In a country where everything in life and art was of concern to the censors, and arts involving words, with their infinite capacity for subversion, were of most special concern to the censors, a high-level bureaucrat like Sonnleithner was a good man to have on one's side. That weighed as heavily as his skills as a librettist, which at that point were largely untested anyway.

Sonnleithner's short tenure as director of the Theater an der Wien resulted from a shake-up that resolved Beethoven's sticky contract situation with his nominal employer and ex-librettist Schikaneder. In the beginning of 1804, Baron Peter Anton Braun, who managed both court theaters, bought the Theater an der Wien. Shortly after, Braun fired Schikaneder as director of the theater, whose statue as Papageno presided over the entrance. At that point Beethoven's contract with Schikaneder for an opera was terminated, and he had to move out of the theater. That solved the friction over

Vestas Feuer

, but it was a setback for

Leonore

. Beethoven had been going at the opera full tilt, composing scenes as fast as he could get words from Sonnleithner.

Beethoven had already had run-ins with Baron Braun over performance venues and considered him an enemy. He wrote Sonnleithner, “I know in advance that if everything depends again on the worthy

Baron's

decision, the answer will be

no

. . . his treatment of me has been persistently unfriendlyâWell, so be itâ

I shall never grovel

âmy world is the universe . . . I do not want to spend another hour in this wretched hole.”

28

Soon after, he moved out of the theater and into a flat in the building where his childhood friend Stephan von Breuning lived, known as

das rothe Haus

(the Red House) and belonging to the Esterházy estates. Before long he moved in with Stephan. At that point the two hotheaded Rhinelanders began to work out whether they could get along as roommates.

29

Â

By around April 1804, the score of

Bonaparte

was copied and ready. Prince Lobkowitz had given Beethoven a splendid 1,800 florins for exclusive access to the symphony for six months and made his house orchestra available for trial run-throughs to be heard by invited guests. Beethoven had to have been concerned about the fate of a symphony he knew tested so many boundaries. He was becoming resigned to the deterioration of his hearing and the steady drain of illness. As for

Leonore

, he was uncertain about its performance possibilities as he continued desultorily to work on it.

At the same time, publishing was going well and likewise his reviews, so he had reason to be hopeful about the reception of the symphony. In nearly the whole of an issue with Beethoven's picture on the cover, the

Allgemeine Musikalische Zeitung

hailed the publication of the

Prometheus

Variations in these kinds of terms: “inexhaustible imagination, original humor, and deep, intimate, even passionate feeling are the particular features . . . from which arises the ingenious physiognomy that distinguishes nearly all of Herr v. B's works. This earns him one of the highest places among instrumental composers of the first rank.”

30

When the Second Symphony appeared the journal called it “a noteworthy, colossal work, of a depth, power, and artistic knowledge like

very

few . . . it demands to be played again and yet again by even the most accomplished orchestra, until the astonishing number of original and sometimes very strangely arranged ideas become closely enough connected, rounded out, and emerge like a great unity.” More and more the elements that were special, unusual, even bizarre about his music were becoming the things most admired about it, at least in progressive circles. In other words, critics were beginning to let Beethoven be Beethoven, to sense the unity that lay under the bewildering diversity of his surfaces.

If his musical enemies were fading in strength, his body remained his greatest enemy. Around the time Beethoven moved in with BreuÂning, he became frighteningly ill. When he recovered from the worst of it, he was left with a fever that lingered for months. He began to be attacked by abscesses in his jaw and finger, and a septic foot; eventually the finger problem nearly led to an amputation.

31

To be so physically beset in the middle of preparing for the symphony readings and trying to keep

Leonore

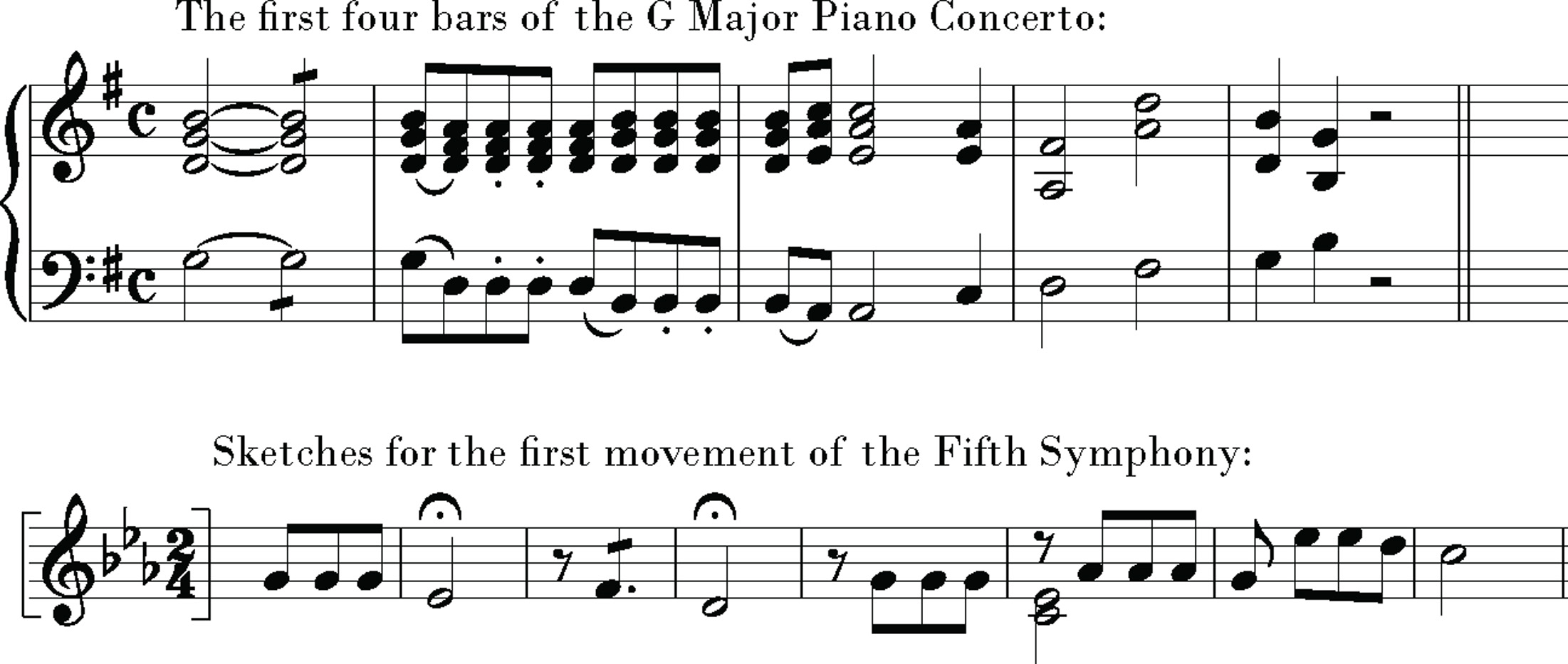

afloat made him more brittle than usual. And there were other projects demanding attention. In the middle of sketches for the opera he jotted down two ideas, one the beginning of a piano concerto and the other the beginning of a symphony, one idea gentle and the other dynamic but sharing a common rhythmic motif. Here he found the leading ideas for his greatest concerto and eventually his most famous symphony.

Â

Two Beethoven Sketchbooks

Â

As plans heated up for readings of the new symphony and other new pieces with Lobkowitz's orchestra, in late May of 1804, Ferdinand Ries turned up at Beethoven's flat with stunning news: the puppet French Senate had just declared Napoleon Bonaparte to be emperor of France. For Beethoven this was not just an interesting or shocking piece of information; it concerned him intimately. Ries had seen the copyist's score of the new symphony lying on a table in his room, with its title page: at the top,

Bonaparte;

at the bottom,

Luigi van Beethoven

.

Now Beethoven heard that the hero he had admired as a liberator, so much that he shaped his most ambitious work around him, had made himself an emperor. Beethoven did not stop to think about the practical questions, did not try to gloss over the import of this news. He grasped quite clearly what it meant. Napoleon was no liberator but was in it for his own power and glory. In a transport of rage, Beethoven cried to Ries, “So he too is nothing more than an ordinary man! Now he also will trample all human rights underfoot, and only pander to his own ambition. He will place himself above everyone else and become a tyrant!” He snatched up the title page of the symphony, ripped it in two, and threw it to the floor.

32

If that was said and done as Ries remembered it years later, Beethoven was correct in every respect. In his response, the news hit him in terms of ideals and history. He understood that now the revolutionary dreams of the 1780s were finished, because Napoleon had been the only man able to realize them. The Revolution is dead; long live the Revolution.

But of course, Beethoven did not throw out the Third Symphony. When the parts were published in 1806, the title would read

Sinfonia eroica, composta per festeggiare il sovvenire d'un grand'uomo:

“Heroic symphony, composed to celebrate the memory of a great man.” It was a finely considered title. The great man in memory was the beau ideal Beethoven and so many others had taken Napoleon to be. That imaginary hero was dead and buried, while Napoleon himself continued to triumph on the battlefield. More than the death of a hero, now the symphony marked the death of a dream.

But the vanished title did not erase the connection of the symphony to Napoleon in its foundation and in Beethoven's mind. It did not even fully erase his name from the manuscript. In August 1804, offering the symphony and a pile of other new works to Breitkopf & Härtel, Beethoven noted, “[T]he title of the symphony is really

Bonaparte

. . . I think that it will interest the musical public.” A title page of the symphony survived, with a date of that same month in another hand. On the top of the page, the words

Intitulate Bonaparte

have been erased so violently that some of it has chewed right through the paper. When Beethoven was enraged at a thing or a person, he hated to see the very name or word. Yet at the bottom of the page, in pencil in Beethoven's own hand, are the words

Geschrieben auf Bonaparte

, “written on Bonaparte,” and that has not been erased. Here is a graphic representation of the ambivalence that was seen all over Europe. Napoleon himself defined it: “Everybody has loved me and hated me,” he said. “Everybody has taken me up, dropped me, and taken me up again.”

33

His enthronement, the central symbolic event of Napoleon's career, elevated to myth the day it happened, came on December 2, 1804. Amid stupendous pomp and ceremony in the Cathedral of Notre Dame in Paris, in the presence and with the blessing of Pope Pius VII, Napoleon placed the Charlemagne Crown on his head as emperor of France.

34

That he crowned himself was the ultimate symbol of this self-made conqueror, now a self-made emperor. With that he declared himself Charlemagne's successor, and thereby symbolically erased the thousand-year succession of emperors of the Holy Roman Empire down to the present Emperor Franz II. Napoleon was no longer the dictator of a nominal republic; he was the founder of a new hereditary line of sovereigns, on the model of the ancien régime that the Revolution believed it had annihilated once and for all.

Among the French government's decrees of the next months was an Imperial Catechism, which the church was directed to teach to all children of the soi-disant republic that was in fact a dictatorship. This new catechism included these responses:

Â

Q. Why are we obliged to all of these duties to our Emperor?

A. First, because God, who created empires and distributes them according to His will, in heaping on our Emperor gifts, both in peace and war, has established him as our sovereign and rendered him the minister of his power and image on earth. To honor and serve our Emperor is thus to honor and serve God himself.

Q. What should one think of those who fail in their duty to the Emperor?

A. According to the Apostle Saint Paul, they would be resisting the order established By God Himself, and would render themselves worthy of eternal damnation.

Q. What is forbidden to us by the Fourth Commandment?