Beethoven: Anguish and Triumph (125 page)

For the summer of 1823, Beethoven was invited to stay at the house of a Baron von Prony at Hetzendorf. Perennially disgusted that his noble patrons were not more generous with him and did not treat him as an equal, he found this patron annoyingly worshipful, bowing and scraping and following him around. Beethoven took to playing as loudly as he could above the baron's bedroom at night, until his victim regretfully sent him packing.

95

From there, in mid-August Beethoven headed for Baden. Now, he was suffering from a painful and dangerous eye infection. In Baden his friends worried about that, and also that he was eating too much of his favorite fish with eggs and macaroni. His irritability with life in general and with Anton Schindler in particular led to a stern letter to Schindler in May: “When you write to me, just write in exactly the same way as I do to you, that is to say, without giving me a title, without addressing me, without signing your name . . . And you need not use figures of speech, but just say precisely what is necessary.” Soon he was back to teasing Schindler as “Samothracian scoundrel!,” sending him on errands, reporting his health: “I have to bandage my eyes at night and must spare them a good deal, for if I don't, as Smetana [his doctor] writes, I shall write very few more notes.”

96

More dissonance was on the way in the form of a new disaster from brother Johann and family. But amid the contrapuntal miseries, Beethoven had to have been satisfied that after so much trouble, so much illness, so much pain, near complete deafness, and years of rumors that he was crazy and written outâtheories he at times had come close to believing himselfâhe had in a few months completed the mass and the

Diabelli

Variations, which he knew were among the crowning works of his life. The first was his magnum opus so far, the second the summit of his piano variations and somewhere near the summit of all his piano music. Both works involved old heroes and models. With the mass, he had put himself on the plane of Handel, with the op. 120 Variations on the plane of J. S. Bach.

Â

The long genesis of op. 120 had begun in 1819, with Diabelli's little waltz and an invitation to join a collection of fifty composers in writing a single variation on it. This was a scheme to advertise Diabelli's new publishing house with miniatures composed by a row of famous names. For Beethoven, writing the requested variation could have been a throwaway or a source of quick cash. So why did he decide to make what he called this

Schusterfleck

, “cobbler's patch,” the foundation of the most elaborate piano work of his life, one that, like the

Missa solemnis

and the

Hammerklavier

threatened to become unwieldy, impractical, hard to sell?

Â

Â

No matter how desperate Beethoven was, his artistic goals came first. With serious works, he wrote what he wanted, how he wanted, and then worried about how to sell it. Some of what lay behind the

Diabellis

seems simple enough. He had written variations since childhood, starting with his first published piece at age ten. Now if he was going to write a set, it was going to have the epic quality of most of his serious pieces in these years. As usual, this one was involved with models. To take something simple and inconsequential in itself and in a set of variations make it into something rich and unexpected was Haydn's game. Once again Beethoven took up his model and amplified it. As he became more concerned with the transcendent and sublime, he was also more concerned with the ordinary and everyday, like the raunchy folk tunes that followed the exquisite first movement of op. 110.

The ideal of simplicity had been with him from early on, something he learned from Handel and Haydn and Mozart, and from the folk music he had known from childhood and worked with later in his dozens of folk-song arrangements. “Please please please keep it simple,” he wrote on a sketch for the Mass in C. The simple bass line in

The Creatures of Prometheus

represented the creatures unenlightened by art and feeling, mere moving clay. Like that commonplace bass line that became the germ of the

Eroica

, the creatures of Prometheus had infinite potential. Schiller said that every artist aspires to create form that transcends content.

Prometheus

and the

Eroica

exemplify that principle, using form to give meaning to the meaningless.

At times there is another side to Beethoven's concern with simplicity, pushing that concern a degree further into irony, parody, even a kind of aesthetic cynicism: the implication that the fundamental material of a piece is not so important, that it may as well be one thing as another. It was in this spirit that once in a soiree Beethoven took a cello part of his would-be rival Daniel Steibelt, turned it upside down, picked out a few notes at random, and on that foundation proceeded to improvise with his usual brilliance. In that same spirit of irony and bravado he seized Diabelli's

Schusterfleck:

I can take anything at all, parody it, laugh at it, and still make something magnificent out of it, far beyond anything anybody including its originator could imagine doing with it

. Here he is close to mainstream Romantic irony, like those writers who in their works turned around to look at their material and themselves as if in a mirror, reminding the reader of the artifice before them, the artist grieving and laughing over his own creation.

There is a still-deeper layer to Beethoven's interest in taking up the ordinary and raising it toward the sublime. Apart from the grandfather he was named for, a first-rate musician, he came from ordinary people with ordinary jobs, ordinary troubles, ordinary tragedies. In the popular myth, so did Napoleon Bonaparte. Beethoven understood that, like Napoleon, he had on the foundation of his natural gifts lifted himself from the ordinary to the extraordinary by the forces of his labor, discipline, and vision. Both of them were men like the creatures of Prometheus, rising from the common clay of humanity, but in their case the rise was self-willed.

So Beethoven took up Diabelli's rattling little barroom tune with a certain cynical delight in its trashiness, and proceeded to transmute this ordinary dreck into gold. Ultimately, after all, as with Steibelt's cello part it didn't much matter where he startedâand he wanted the world to understand that. The piece begins with nothing, just as he entered history as a mewling infant of a struggling family in a freezing church baptistery. What made the difference was what he did with his life, and in this piece what makes the difference is what he does with a meaningless waltz, to transmute it into meaning.

So parodistic intentions were part of the game from the beginning. The fundamental tone of the work, like other of his piano variations including the

Prometheus

set, is ironic and comic. Call the

Diabelli

Variations a kind of sublime prank, in the sense of what Goethe called

Faust:

“a very serious joke.”

He sketched twenty-two variations in 1819, in the first burst of fervor for the work, but laid aside the piece to take up the

Missa solemnis

, some new bagatelles, and the last three piano sonatas.

97

In 1819, a big set of variations had been an ideal project for him, trying as he was to get past years of relative inactivity by his standards, past his creative uncertainty and struggles with health and courts. The

Hammerklavier

had been a major sustained effort. The

Diabellis

were to be a series of miniatures that could be discovered in improvisation, sketched quickly, revised and polished in bits and pieces, arranged and rearranged like a collection of gems. Alone at the keyboard he probably improvised dozens if not hundreds more variations that never reached paper.

There is one metaphor for the

Diabellis:

a string of multicolored gems. Or a parade of bagatelles, a galaxy of tiny worlds, a collection of poems on a common theme. Or portraits of Beethoven himself, who contained worlds. Or all of life and music in a series of lightning flashes: here wistful, here absurd, here dancing, laughing, remembering, weeping. Improvisation and variation had always been his wellspring, his engine. In the

Diabelli

Variations he made those intertwined arts the substance of the music. Perhaps more than anything else, his first work on the project got his creative engine up to speed again.

In the

Diabellis

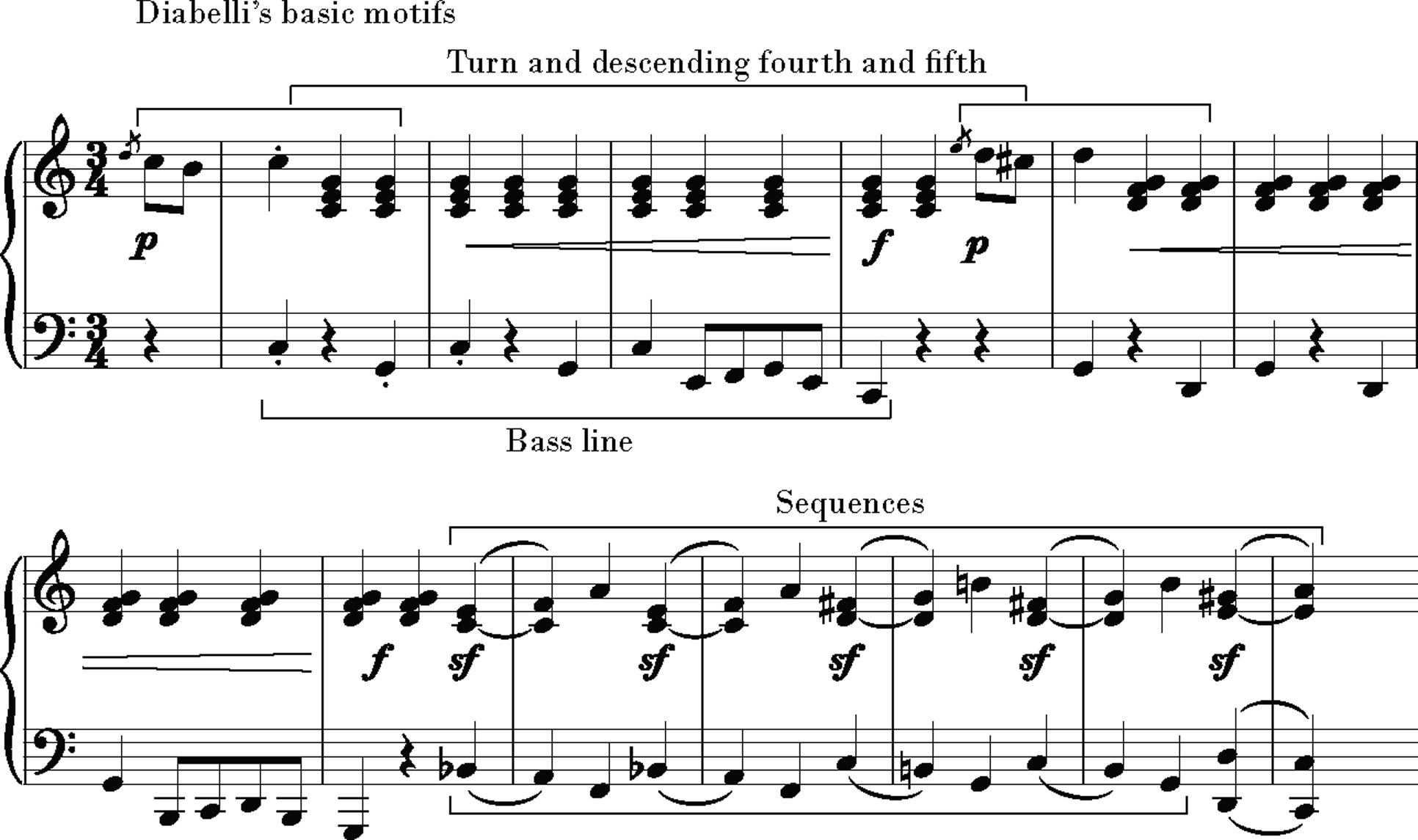

we see a fundamental aspect of Beethoven's technique in a nutshell.

The beginning is central

, every part of that beginning: melodic, harmonic, rhythmic, coloristic, emotional. Now the fundamental material is somebody else's tune, but the handling is the same, carried to a new level. While every aspect of Diabelli's theme is going to be grist for the mill, some elements will be steady leading motifs:

Â

Diabelli Variations

Â

All Beethoven's variations have an overarching plan. The plan here is among his loosest but is still consistent, and it is made evident in the first three variations: Variation I is comically pompous, no. II light and mercurial, no. III lyric and pensive. As established in those first variations, the principle is going to be constant kaleidoscopic contrast. For the purpose of establishing that idea, the mercurial second variation was one of the last he composed, as he finally closed in on how to lay out the elements.

98

Beethoven surely knew Bach's

Goldberg

Variations, already famous and called a summit of the genre, likewise founded on a simple dance tune. The

Goldbergs

âand

The Well-Tempered

Clavier

âwere further models for the

Diabellis

in their conception and sometimes in their sound.

Beethoven was not interested in a structure like the

Goldbergs'

systematic one of groups of free variations regularly marked off by canonic ones. Here and there in the

Diabellis

two variations are joined, here and there one seems to be an answer to the previous, but mostly the order is loose, founded on contrasts calculated to sustain an impression of capriciousness and play.

99

All but two variations are in the C major of the theme (also including the familiar

minore

, a turn to C minor), but within each variation he went for maximum harmonic contrast, much chromaticism, internal modulations.

100

For one example of the tonal variety he injected into the theme, the C-minor ÂVariation XIV has a passage in D-flat major, which is nowhere hinted in the theme.

When Beethoven returned to the piece in 1823, he added eleven more variations, including the first two.

101

The final Variation I solved a problem he had left hanging in 1819, when the set started with the lyrical no. III: to follow the garishness of Diabelli's waltz with that quietly pensive and entirely Beethovenian variation was too big a jump. Instead, his new addition follows the theme with a faux-majestic march, forming a parody of the theme.

102

That march of Variation I is unlike anything else in the genre, in which the theme is always the beginning and, in a way, sole proprietor. Here Beethoven's first variation is more weighty, a second beginning, in which he lampoons the theme in his own voice.

Then the poems, the variegated gems, tumble out one after another, some breathlessly short like the scampering Variation II, some broad and inward, like no. III, some parodistic. Each of Beethoven's piano sonatas had been a distinctive individual with a distinctive handling of the instrument. Here that quality is boiled down to brief moments, each of them memorable. In this period Beethoven wrote Ferdinand Ries that the ideal for art was the combination of the beautiful and the unexpected. Here every moment is beautiful and unexpected.

Flowering and dancing and jumping, sparkling and singing, introverted and extroverted, the little worlds unfold. Variation XIII, with its jumpy starts and stops, is the most broadly comic yet in its parody of the theme. Next comes one of the surprises: no. XIV is in a richly chordal C minor with an ornamented melody marked Grave e maestoso, recalling the style of a Bach prelude.

103

For Beethoven, to write variations looks back to his first pieces, back to how he learned to compose by writing variations: taking a single piece of material through the most varied avatars. To pay homage to Bach is to look back at his childhood as well, when he grew up playing the

WTC

. It is also to look back at music itself. Here is another feature of Beethoven's late work: often it is

music about music

.

104