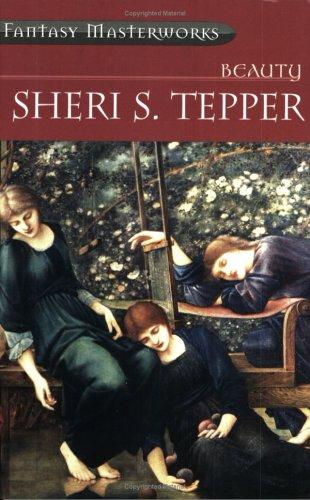

Beauty

Authors: Sheri S. Tepper

Tags: #Epic, #General, #Fantasy, #Masterwork, #Fiction, #Science Fiction

Beauty

Sheri S. Tepper

Fantasy Masterworks Volume 14

eGod

FOREWORD

In the pages that follow, there are certain interpolations written by me, Carabosse, the fairy of clocks, keeper of the secrets of time. When I stand on the bridge above my Forever Pool, I see all past and future things reflected, near or far, dim or plain. If I invite others to stand beside me, they too may see.

That which we do, we do because we see.

This journal is written by Beauty, daughter of the Duke of Westfaire, recipient of many pleasant gifts. Though it is regrettable that no one gave her the gift of intelligence (a gift not highly valued in Faery) she has a practicality that often makes up for that lack.

Intelligent or not, she is the coffer that hides our treasure.

Intelligent or not, Beauty is all our hope.

THE JOURNAL OF BEAUTY

the daughter of

THE DUKE OF WESTFAIRE

Getting started on this writing, I cut five different quills and ruined them all. Father Raymond finally cut this one for me. I told him he must, since he gave me the book as a reward for good progress in Latin, rhetoric, and composition, and for going a whole month without complaining. Now I have a place to write all the things I cannot say to anyone, except to Father Raymond, and sometimes he is too busy to listen. It is my intention to tell the story of my entire life so when I am aged I can read it and remember everything. Old people often do not remember things. I know because I have asked them, at least the ones around here, and they usually say something like, "Beauty, for heaven's sake, child, I just don't remember."

If I had a mother I would ask her. I never knew my mother. That is probably as good a place to start as any.

1

MY LIFE IN WESTFAIRE

ST. RICHARD OF CHICHESTER'S DAY, APRIL, YEAR OF OUR LORD 1347

I never knew my mother. My father never speaks of her, though my aunts, his half sisters, make up for his silence with a loquacity which is as continuous as it is malicious. The aunts speak no good of her, whoever she was and whatever has happened to her, specifics which they avoid, however much ill they find to mutter about else. I have always thought they would not waste so much breath on her if she were dead, therefore she is probably alive, somewhere.

De mortuis nil nisi bonum,

Father Raymond says, but that only applies to dead people.

When I was very young I used to ask about her. (As I think any child would. It wasn't wickedness.) First I was hushed, and when I persisted, I was punished. Nothing makes me angrier or more intent upon finding out things than having people refuse to tell me. I don't mind when people don't know, not really, but I hate it when they just won't tell. It's not practical, because it just makes others more curious. It was the aunts whispering about things that started me upon the habit of listening behind doors and dallying outside open windows. Father Raymond reproaches me for this when I confess it, though he admits it is not a very great sin. It was my own idea to confess it because it felt slightly wicked, but perhaps curiosity is not really a sin at all and I need not feel guilty about it. I will try not confessing it for a while, and see.

Sometimes I hear my mother's name, Elladine, and references to "the Curse," or "the Curse on the Child." The Child is presumably me. If I had known what a curse was during my more tender years, I might have been irremediably warped or wounded. As it was, I knew no more what a curse was than what a mama was, except that most children had not the one, but had the other, and that I had had both without getting any discernable good out of either. Now that I am older and know what a curse is, though not the particulars as they may relate to myself, I am used to the idea and I do not find being cursed as frightening as I probably should.

(I know I am being loquacious. Father Raymond says I am very loquacious and affected. I don't really think I am affected, unless it is by the aunts, and if it is by the aunts, how could I help it? All these words are something I was born with. Words bubble up in me like water. It is hard to shut them off.)

I have resolved to find out all about Mama (and the curse) as soon as I can. So far I have not found out much. I do know that Mama was very beautiful, for one of the older men-at-arms said so when he told me I look much like her around the eyes though the rest of me seems to be purely Papa. Papa is an extremely handsome man, and therefore I am very beautiful. It is not conceit which makes me say so. It is a fact. One must face facts, or so the aunts are fond of saying, though they don't do it at all. They say many things they don't do. I've noticed that about people. The fact is that I shall be ravishing when I grow up if I continue in good habits and do not take to drink.

Aunt Lovage, I regret to say, is a tippler, though the other aunts are quite abstemious.

Father Raymond took over teaching me when I was ten or eleven years old, but my earliest memories are of an education supervised by the aunts. I learned cookery from Aunt Basil and wines from Aunt Lovage, sewing from Aunt Marjoram (who was herself educated by the Sisters of the Immediate Conception at St. Mary of Perpetual Surprise) and music from Aunt Lavender who, though tone deaf, plays upon the lute with great brio and a blithesome disregard for accuracy. She refers to her style as "spontaneous," and urges me to emulate it.

I have found I can play the right notes quite as easily as the wrong ones, though to satisfy Aunt I do flap my arms rather more than the music requires. I am quite talented in music. I am told I sing nicely.

When I was four or five, Aunt Tarragon taught me my letters in order that I could read improving works and be confirmed in the faith. Some of the writings I like best do not feel very improving, though whenever Aunt Terror is around I pretend I am reading religious books. I was confirmed when I was nine, rather late in life, truly, though Father Raymond considered it soon enough. Even then I thought some bits and pieces of doctrine were unlikely at best. Aunt Tarragon is very pious. The other aunts call her the Holy Terror-a play upon her name. They say things like, "Where's the Holy Terror gone?" and collapse in silly laughter.

It was my grandfather's notion to name his seven daughters after herbs, a black mark in the heavenly score book which was no doubt wiped clean by his death or enslavement at the age of seventy-four while on his way to Rhodes to offer his services to the Knights Hospitaler of St. John. We are a long lived family, so Papa says, and Grandfather was still very hale and fervent at that age. Grandfather's ship was blown off course in a storm and was taken subsequently by Mamluks, so Grandmama was informed by an escaped survivor. From what Papa and the aunts say about him, I doubt Sultan al-Maluk an-Nazir had any pleasure of Grandfather.

Luckily, Grandfather's demise or disappearance came long after he brought home the builders who saw to the reconstruction of Westfaire Castle. Some say the architects were pagans from the Far East, and some say they were inheritors of the Magi, but they could not have been anything evil to have built so beautiful a place. There is no other castle like it in England; there may be no building like it in the world. Westfaire is without peer. Even those who have traveled to the far corners of the earth, as Father Raymond did in his younger years, say it is of matchless beauty.

Grandfather's first wife had no sons and two daughters. They are eldest of my aunts, Aunt Sister Mary Elizabeth and Aunt Sister Mary George, who are nuns at the Monastery of St. Perpituus in Alderbury. The sisters do not visit us often. I believe they took holy orders simply to escape being called Tansy and Comfrey, though it is possible they were summoned by God. Sister Mary Elizabeth was rather infirm when I last saw her, though it is likely Sister Mary George will go on forever, getting a little leaner and drier with every passing year.

Grandfather's second wife had no sons and five daughters. Aunt Lavvy, at fifty-eight, is the youngest of them. Aunt Love is sixty. Aunt Terror is sixty-two. Aunts Bas and Marj are twins of sixty-five. I am almost sixteen, and the difference in our ages (as well as their reticence about things I want to know) seems an impenetrable barrier between us. They often fail to perceive the things I perceive, and this makes communication between us exceedingly difficult. I cannot say that there is more than a superficial affection on either side of our relationship. Father Raymond talks about filial duty, but it seems to me there should be something more in a family than that.

Grandfather's third wife, my father's mother, died soon after Grandfather vanished, of grief it is said, though in my opinion she died of simple exasperation. I sometimes imagine what it would be like to be wife to a man and mother to a son who are always off on pilgrimage, as well as being stepmother to seven daughters, all of them considerably older than I. I would die of it, I think, just as Grandmama did. She was only fifteen when she married Grandfather, after all, and about thirty-five when he was killed. What had she to look forward to but decades more of the herbal sisters, all of them dedicated to eccentric celibacy? Buried among all those stepdaughters, Grandmama would have been unlikely to find a second husband, especially since there was nothing left of either her dowry or her dower. Grandpapa used everything rebuilding Westfaire: all the dowries of his three wives, all his own money, and all the considerable fortune he had somehow obtained in the Holy Land, about which people say very little, making me believe Grandfather may not have been quite ethical in amassing the treasure. Grandmama was left with nothing to attract suitors, and death might have seemed a blessed release. At least, so I think.

I spend a lot of time thinking about people. If one leaves out religion, there is very little to think about

except

people. People and books are just about all there is. I don't have anyone much to talk with and only Grumpkin to play with, so ... so I spend a lot of time thinking. It comes out in words. I can't help that.

I do read everything I can get hold of. Books and my own writings are a comfort to me in the late hours of the night when all in Westfaire are asleep but me, and I am awake for no reason that I know of except that my legs hurt (Aunt Terror says it is growing pains) or the owls are making a noise in the trees, or my head is full of things I have do not have enough words for yet-there must be such things!-or my chest burns as it sometimes does, as though I had swallowed a little star. It burns and burns, just behind my collar bone, as though it were trying to hollow me out to make a place for itself. I do not know what it is, but it has always been there.

So, I sit up in my bed with the bed curtains drawn tight, the candle on one side and Grumpkin snoring into his paws on the other, and make lists of new words I have heard that day or write pages to myself about all the things I do not understand. Grumpkin lies on his back with his tummy up, his front feet folded over his chest or nose and an anticipatory smile on his face, as though he is dreaming of mice. I wish I could sleep like cats do.

2

DAY OF ST. PATERNUS, BISHOP, CONVERTER OF DRUIDS, APRIL, YEAR OF OUR LORD 1347

When I was quite young, about eight or nine, I purloined some boy's clothes from a line near the woodsman's hut, leaving a silver coin in their place. I had gone out of my way to steal the coin, too, because I had no money of my own, and I thought that though God might forgive my robbing the well-to-do, he would not forgive my increasing the distress of the poor. Dressed in these uncouth garments, dirt on my face, and with my hair twisted up under a grubby cap, I presented myself at the stables asking for whatever work Martin, the head groom, could give me. I am fairly sure Martin knew who I was, but we both preserved the fiction that I was a boy from the countryside, one Havoc, a miller's son, whom Martin employed in order to take advantage of youthful enterprise. If we had ever been found out, I would have sworn on the Holy Scripture that he was guiltless, so grateful to him I was, and I believe he relied upon my protection in the event our game was discovered.

It was in the stable I learned to ride long before the aunts had me dressed in voluminous skirts and perched upon a sidesaddle, one of Grandfather's inventions. I do not think the sidesaddle will catch on. Most women ride sensibly astride, and I cannot imagine their giving it up for something both so uncomfortable and of such doubtful provenance. According to the stable boys, the sidesaddle was designed to protect a maiden's virginity, while risking the maiden's neck. Risking rather much for rather little, I thought at the time, though of course I knew nothing practical about the matter then and scarcely more today.