Beatles vs. Stones (33 page)

Read Beatles vs. Stones Online

Authors: John McMillian

Tags: #Music, #General, #History & Criticism, #Genres & Styles, #Rock, #Social Science, #Popular Culture

Complaints about the Stones reached a pitch in the summer of ’89, when they launched their

Steel Wheels

tour. They didn’t have a lot going on musically, so as if to compensate, they put on the most freakishly bombastic rock production the world had ever seen. The stage was some kind of dystopian megastructure: an asymmetrical tangle of scaffolding, catwalks, and balconies that was fitted with blinking lights, fog machines, and flame-shooting turrets. When the Stones played “Honky Tonk Women,” gigantic inflatable dolls swelled up alongside the stage. When Mick sang “Sympathy for the Devil,” he stood from a ledge over one hundred feet high, shrouded in smoke, as the structure beneath him appeared to burst into flames. Every show ended with a coruscating fireworks display.

Bill German, a Stones fanatic who used to publish the pre-Internet

fanzine

Beggars Banquet

, saw the Stones as often as he could on that tour, and he noticed an “interesting irony” in their approach.

“As much as Mick professed his love for the new music and as much as he despised the ‘retro rocker’ label, he was hesitant about adding the band’s new songs to the repertoire.”

Mick wanted each song, be it “Brown Sugar,” “Tumbling Dice,” or “You Can’t Always Get What You Want” to sound exactly like the original album version. By seeing a lot of new and commercially successful acts . . . Mick got a sense of what was going on in the music industry. He learned the way to reach the vastest audience . . . was to play the hits the way people remembered [as opposed to experimenting with the songs’ arrangements]. . . . Most baby boomers want “Gimme Shelter” the way they heard it in their dorm room twenty years ago, so that’s how we’ll give it to them. It was more a business decision than an artistic decision, but it worked.

Meanwhile, the Stones took the corporate sponsorship of rock ’n’ roll to gaudy new heights. In 1981, they inked a deal with Jovan, a perfume company. The group’s main benefactor during the

Steel Wheels

tour was Anheuser-Busch, the brewing conglomerate, which paid them at least $6 million (some sources say more). Now the Stones’ expensive concert gear was available at department stores, including Macy’s and JC Penney. You could buy

Steel Wheels

boxer shorts, wallets, and commemorative coins. The Glimmer Twins even appeared on the cover of

Forbes

.

“What Will They Do With All That Money?” the magazine asked.

Their age was becoming an issue as well. It wasn’t that anyone held a grudge against the Stones for getting older, but rather that they were so outlandishly undignified about it. In the mid-’80s, when Mick began attending to his solo career, he was plainly aping the music and mannerisms of much younger acts, like Prince, Michael Jackson, and

Duran Duran. In 1989, Bill Wyman, aged fifty-two, married eighteen-year-old Mandy Smith. And of course, people sniggered about the Rolling Stones’ nostalgia-peddling “Steel Wheelchairs Tour.”

Again, that was

twenty-five years ago

. Other artists who have remained popular with baby boomers have always continued to evolve, whether for better or worse. (Bob Dylan and Bruce Springsteen are both prime examples.) But the Stones haven’t seemed musically audacious for a very long time—not since they experimented with some of the trendy disco sounds of the late ’70s and early ’80s. (And even the hits they had back then, like “Miss You” and “Emotional Rescue,” now seem like duds.) Nor did the Stones return to their roots in blues music, which—unlike rock—is something that old men (if they are talented enough) can perform with dignity. Instead, the Stones drenched themselves in self-parody and inflated ballyhoo.

Nowadays, the Rolling Stones scarcely bother trying to make new music—they’ve recorded only two completely new songs since 2005—but in 2012 they made an awfully big deal about their fiftieth anniversary. To help out with all the celebrative merchandising, they hired graphic design artist Shepard Fairey to update their infamous lips and tongue logo. They put out a coffee table book (

The Rolling Stones Fifty

), a biographical film (

Crossfire Hurricane

, directed by Brett Morgan), and they released yet another career retrospective of old hit singles, titled

GRRR!

Depending on how one counts it is perhaps the twenty-fifth Rolling Stones compilation album.

And of course the Stones launched their

50 & Counting

tour, which began in Paris and London in late 2012, and came to the United States shortly thereafter.

Way back in 1975, Jagger said, “I’d rather be dead than sing ‘Satisfaction’ when I’m 45,” but now he and Keith were both just shy of seventy. Naturally, they played “Satisfaction” at nearly every stop. (It was an encore song.) On some nights, their set lists did not contain a single number that was written after 1981.

Most concert reviewers gave the Stones solid marks. The standard

rap was that even in their dotage, the Stones were still capable of delivering an exciting performance. They played their old hits to a surefire audience, and everyone had a good time. Nevertheless, some fans found it hard to regard the

50 & Counting

tour as much more than a sordid money grab.

On average, the Stones charged $346 per ticket. For the most part, only very affluent adults could afford to attend. The Stones wound up grossing about $100 million from just eighteen shows.

Then again, music is a powerful memory cue; it can summon nostalgia like little else, and that can be a potent and wonderful thing. Certainly many Beatles fans remain deeply disappointed that they never got a chance to hear another studio album or see the group perform. The Portuguese have a fine word for that feeling:

saudade.

It’s a kind of longing for something that one has never experienced, or a keen desire for something that cannot exist.

Paradoxically, however, by refusing to reunite, the Beatles may have actually enhanced their legacy. Unlike so many other fabled pop and rock acts from the ’60s and ’70s, the Beatles retired while they were near the top of their form. They didn’t dilute their catalogue with a string of mediocre records, and they didn’t reinvent themselves as a touring act, hawking their hits from thirty and forty years ago to well-heeled baby boomers.

True, Apple continued putting out invaluable Beatles material long after the Beatles dissolved their partnership, including

Live at the BBC

in 1994 and

The Beatles Anthology

in 1995 (which was at once a documentary television series, six CDs worth of unreleased material, and an oral history). As part of that ambitious project, Paul, George, and Ringo even released two “new” Beatles songs––“Real Love” and “Free as a Bird”––which were built around Lennon’s singing voice on some old demo recordings that Yoko Ono had been safekeeping. All of the ex-Beatles went on to have successful solo careers, and recently, Paul McCartney has been putting on some magnificent, nostalgia-filled concerts of his own. But of course the Beatles never carried on

qua

Beatles. In a sense (and unlike the Stones) the Beatles never even grew old.

They didn’t have the chance.

Hollow-point bullets are designed to expand as they hit their target, causing maximum tissue damage. In New York City, on December 8, 1980, two of them pierced the left side of Lennon’s back, and two more entered his left shoulder. They were “amazingly well-placed,” said Dr. Stephen Lynn, who treated Lennon at the emergency room at Roosevelt Hospital.

“All the major blood vessels leaving the heart were a mush, and there was no way to fix it.”

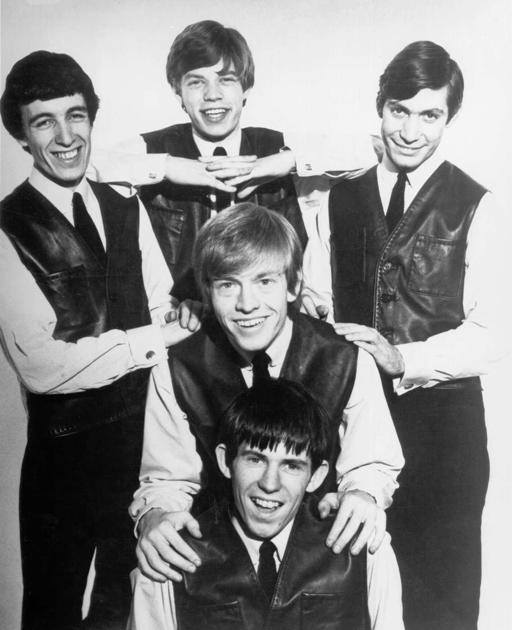

The Beatles in Hamburg: Pete Best, George, John, Paul, and Stu Sutcliff. Scholars agree that the Beatles’ experience in Hamburg was formative.

Astrid Kirchherr/Ginzburg Fine Arts

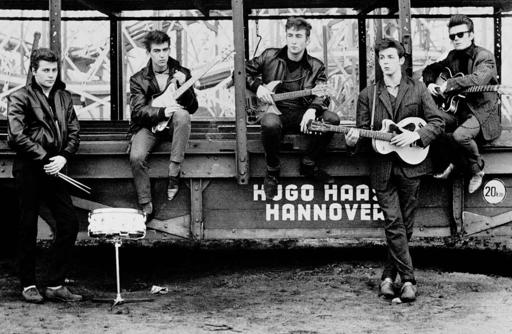

At the Cavern Club in Liverpool, Pete Best on drums.

Michael Ochs Archive/Getty Images

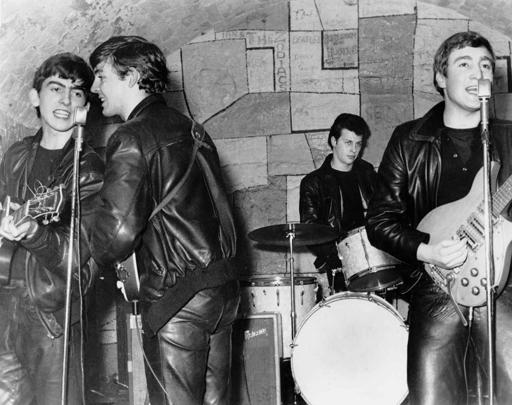

Beatles’ manager Brian Epstein.

John Rodgers/Getty Images

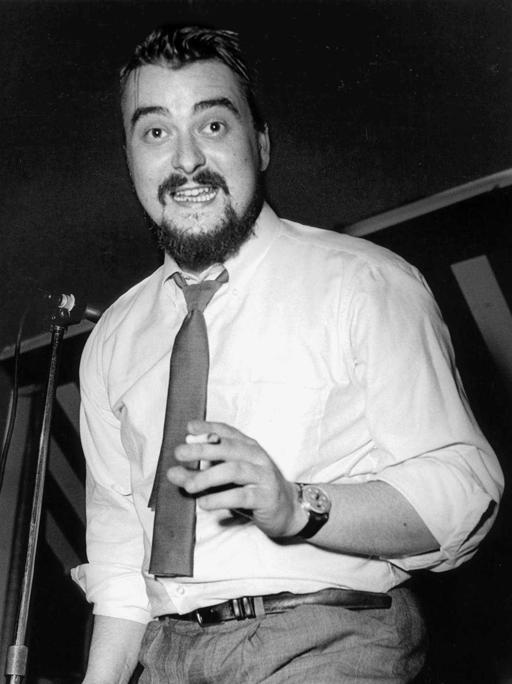

Giorgio Gomelsky gave the Stones their first big break—a residency at the Crawdaddy Club—and he introduced them to the Beatles.

Jeremy Fletcher/Getty Images

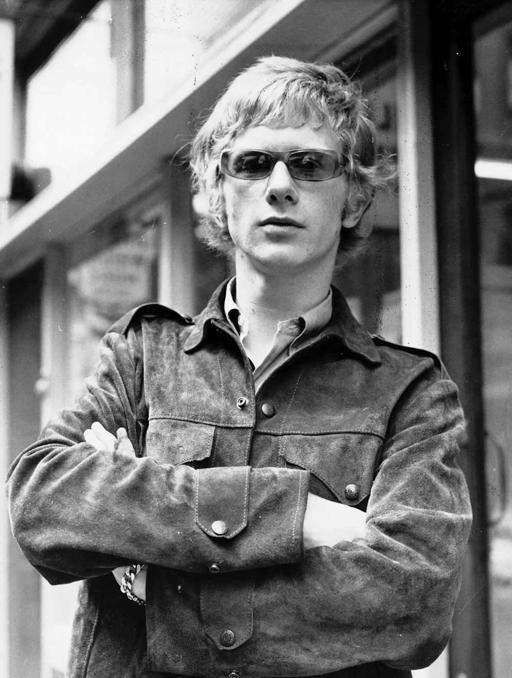

Andrew Loog Oldham, manager of the Rolling Stones. He said he wanted to be known as “a nasty little upstart tycoon shit.”

Richard Chowen/Getty Images