Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era (117 page)

Read Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era Online

Authors: James M. McPherson

Tags: #General, #History, #United States, #Civil War Period (1850-1877), #United States - History - Civil War; 1861-1865, #United States - History - Civil War; 1861-1865 - Campaigns

held firm amid firing so deafening that many soldiers stuffed their ears with cotton plucked from the fields.

The darkness of New Year's Eve descended on a scene filled not with the sound of music but with the cries of wounded men calling for help. Bragg believed that he had won a great victory and wired the good news to Richmond, where it produced "great exaltation." Bragg's dispatch added that the enemy "is falling back."

20

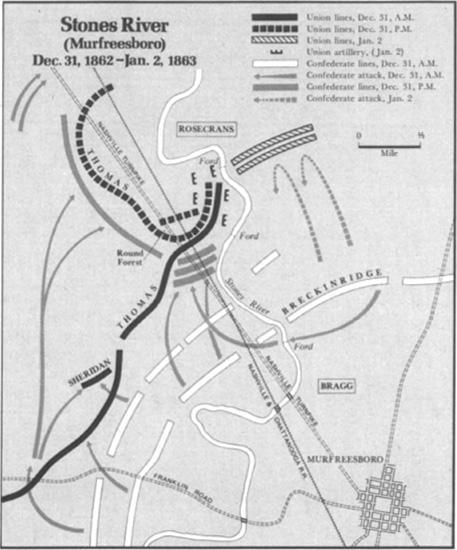

But this was wishful thinking. During the night Rosecrans held a council of war with his commanders and decided to hold tight. Skirmishes on New Year's Day took a few more lives, but the main action on January 1 was the occupation of a hill east of Stones River by a Union division. On January 2 Bragg ordered Breckinridge to clear this force off the hill. The Kentuckian protested that such an attack would fail with great loss because Union artillery on high ground across the river would enfilade his line. Bragg insisted, Breckinridge's men swept forward with a yell and routed the bluecoats, but then were indeed cut down by fifty-eight Union guns across the river and driven back to their starting point by an infantry counterattack, having lost 1,500 men in an hour. This affair added to the growing tension between Bragg and his generals.

Nonplussed by Rosecrans's refusal to retreat, Bragg seemed not to know what to do. But in truth there was little he could do, for more than a third of his troops had been killed, wounded, or captured. The Yankees had suffered 31 percent casualties, making Stones River the most deadly battle of the war in proportion to numbers engaged. When Bragg awoke on January 3 to find the enemy still in place and receiving reinforcements from Nashville, he knew the game was up. That night the rebels pulled back to a new position behind the Duck River, twenty-five miles to the south. For the second time in three months, the Army of Tennessee had retreated after its commander claimed to have won a victory.

The outcome at Stones River brought a thin gleam of cheer to the North. It blunted, temporarily, the mounting copperhead offensive against the administration's war policy. "God bless you, and all with you," Lincoln wired Rosecrans. "I can never forget, whilst I remember anything," the president wrote later, that "you gave us a hard earned victory which, had there been a defeat instead, the nation could hardly have lived

20

.

O.R

., Ser. I, Vol. 20, pt. 1, p. 662, Vol. 52, pt. 2, p. 402; Jones,

War Clerk's Diary

(Miers), 145.

over."

21

The Army of the Cumberland was so crippled by this "victory," however, that Rosecrans felt unable to renew the offensive for several months.

While Washington breathed a sigh of relief after Stones River, dissension came to a head in the Army of Tennessee. All of Bragg's corps and division commanders expressed a lack of confidence in their chief. Senior Generals William J. Hardee and Leonidas Polk asked Davis to put Johnston in command of the army. Division commander B. Franklin Cheatham vowed he would never again serve under Bragg. Breckinridge wanted to challenge Bragg to a duel. Bragg struck back, court-martialing one division commander for disobeying orders, accusing another (Cheatham) of drunkenness during the battle, and blaming Breckinridge for inept leadership. This internecine donnybrook threatened to do more damage to the army than the Yankees had done. Disheartened, Bragg told a friend that it might "be better for the President to send someone to relieve me," and wrote Davis to the same effect.

22

Davis passed the buck to Johnston by asking him to look into the situation and recommend a solution. Johnston passed it back. He found many officers hostile to Bragg but reported the enlisted men to be in good condition with high morale. This dubious discovery prompted him to advise Bragg's retention in command. Davis had apparently wanted and expected Johnston to take command himself. But what Johnston wanted, it appeared from his letters to friends, was to return to his old post as head of the Army of Northern Virginia! If the government desired to replace Bragg, he said, let them send Longstreet to Tennessee. And if they thought that Johnston's supervisory role over the whole Western Department was so important, let them put Lee in charge of it and give Johnston his old job in Virginia. In March the War Department virtually ordered Johnston to take command of the Army of Tennessee. But he demurred on the grounds that to remove Bragg while his wife was critically ill would be inhumane. Johnston himself then fell ill. So Bragg stayed on and continued to feud with his leading subordinates.

23

21

.

CWL

, VI, 39, 424.

22

. Bragg to Clement C. Clay, Jan. 10, 1863, Bragg to Davis, Jan. 17, quoted in Catton,

Never Call Retreat

, 49.

23

. Johnston to Louis T. Wigfall, March 4, 8, 1863, quoted in

ibid.

, 52; Thomas L. Connelly,

Autumn of Glory: The Army of Tennessee

, 1862–1865 (Baton Rouge, 1971), 70–92.

Lincoln handled similar disaffection in the Army of the Potomac with more deftness and firmness than Davis had shown. Demoralization reached epidemic proportions in this army after Fredericksburg. Four generals in the 6th Corps headed by William B. Franklin went directly to Lincoln with complaints about Burnside's leadership. McClellan's friends were declaring that "we

must

have McClellan back with unlimited and unfettered powers."

24

Joe Hooker was intriguing to obtain the command for himself. Hooker also told a reporter that what the country needed was a dictator. Men in the ranks were deserting at the rate of a hundred or more every day during January. Thousands of others went on the sicklist because slack discipline in regimental camps and corruption in the commissary had produced sanitary and dietary deficiencies. Recognizing that he had lost the army's confidence, Burnside offered to resign—suggesting to Lincoln at the same time that he fire Stanton, Halleck, and several disgruntled generals.

Discord in the Army of the Potomac climaxed with the inglorious "Mud March." Unusually dry January weather encouraged Burnside to plan a crossing of the Rappahannock at fords several miles above Fredericksburg. Success would put the Federals on Lee's flank and force the rebels out of their trenches for a fair fight. Some of Burnside's subordinates openly criticized the move. Franklin "has talked so much and so loudly to this effect," wrote an artillery colonel, "that he has completely demoralized his whole command."

25

Even God seemed to be against Burnside. As soon as the general got his army in motion on January 20 the heavens opened, rain fell in torrents, and the Virginia roads turned into swamps. Artillery carriages sank to their axles, men sank to their knees, mules sank to their ears. Confederate pickets across the river watched this with amusement and held up signs pointing "This Way to Richmond." With his army bogged down in the mud, Burnside on January 22 called the whole thing off.

The mortified and furious commander hastened to Washington and told the president that either Hooker, Franklin, and a half-dozen other generals must go, or he would. Lincoln decided to remove Burnside—probably to the latter's relief. The president also transferred a few other

24

. Catton,

Never Call Retreat

, 63.

25

. Charles S. Wainwright,

A Diary of Battle

, ed. Allan Nevins (New York, 1962), 157–58.

malcontents to distant posts. But Lincoln astonished Burnside by appointing Hooker as his successor. Fighting Joe was hardly an exemplary character. Not only had he schemed against Burnside, but his moral reputation stood none too high. Hooker's headquarters, wrote Charles Francis Adams, Jr., archly, was "a place which no self-respecting man liked to go, and no decent woman could go. It was a combination of barroom and brothel."

26

But Hooker proved a popular choice with the men. He took immediate steps to cashier corrupt quartermasters, improve the food, clean up the camps and hospitals, grant furloughs, and instill unit pride by creating insignia badges for each corps. Hooker reorganized the cavalry into a separate corps, a much-needed reform based on the Confederate model. Morale rose in all branches of the army. Sickness declined, desertions dropped, and a grant of amnesty brought many AWOLs back to the ranks. "Under Hooker, we began to

live

," wrote a soldier. An officer who disliked Hooker admitted that "I have never known men to change from a condition of the lowest depression to that of a healthy fighting state in so short a time."

27

When Lincoln appointed Hooker he handed him a letter which the general later described as the kind of missive that a wise father might write to his son. Hooker should know, wrote the president, "that there are some things in regard to which, I am not quite satisfied with you." In running down Burnside "you have taken counsel of your ambition . . . in which you did a great wrong to the country, and to a most meritorious and honorable brother officer. I have heard, in such way as to believe it, of your recently saying that both the Army and the Government needed a Dictator. Of course it was not

for

this, but in spite of it, that I have given you the command. Only those generals who gain successes, can set up dictators. What I now ask of you is military success, and I will risk the dictatorship."

28

Two months after appointing Hooker, Lincoln visited the Army of the Potomac on the Rappahan-nock. The president was pleased by what he saw, and agreed with Hooker's proud description of it as "the finest army on the planet." Lincoln was less enthusiastic about the general's cockiness. The question, said Hooker, was not

whether

he would take Richmond, but

when

." The

26

. Quoted in Foote,

Civil War

, II, 233–34.

27

. Catton,

Glory Road

, 161; Darius N. Couch, "Sumner's 'Right Grand Division,' "

Battles and Leaders

, III, 119.

28

.

CWL

, VI, 78–79.

hen is the wisest of all the animal creation," Lincoln remarked pointedly, "because she never cackles until the egg is laid."

29

III

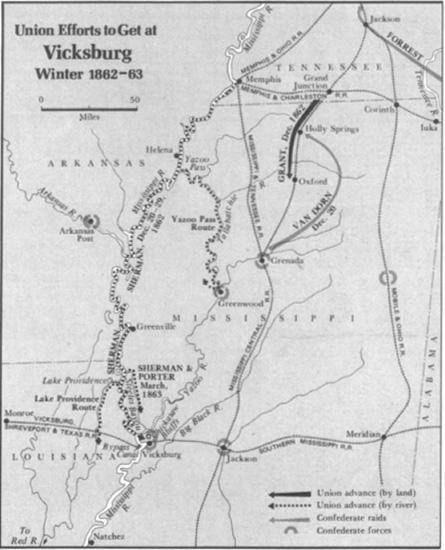

While the armies in Virginia sat out the rest of the winter and the armies in Tennessee licked their wounds after Stones River, plenty of action but little fighting took place around Vicksburg. After the failure of his first campaign to capture this river citadel, Grant went down the Mississippi to Milliken's Bend to take personal command of a renewed army-navy campaign. Nature presented greater obstacles to this enterprise than the rebels. Although Union forces controlled the endless rivers and swamps north and west of Vicksburg, continual rains during the winter made army movements almost impossible and many of Grant's 45,000 men were felled by lethal diseases. High and dry ground east of the city offered the only suitable terrain for military operations. Grant's problem was to get his army to this terrain with enough artillery and supplies for a campaign. Since he had the assistance of the gunboat fleet commanded by David Dixon Porter, Grant hoped to use the high water as an asset. During the winter he launched four separate efforts to flank Vicksburg by water and transport his army to the east bank above or below the city.