Batavia (52 page)

Authors: Peter Fitzsimons

Avoiding the question, Jeronimus begins in reply, ‘Commandeur, I thank the Lord and all providence that you are here. There have been outrages committed in your absence, sir, outrages. Infamy, I tell you, sir,

infamy

!’

And so it goes, Jeronimus denying outright that he has done any wrong and explaining the rest of it away on the evil desires of those who cannot possibly defend themselves because they are dead.

Finally exhausted, the

Commandeur

holds up his hand to cease the apothecary’s confections; this is not a conversation he can afford to continue. The

Commandeur

silently nods to Hayes, who frogmarches the manacled

Onderkoopman

towards the hole, the makeshift prison in the fo’c’sle of the

Sardam

, roughly depositing him alongside the other merchants from the underworld, the worst of the Mutineers, those Devil’s agents.

18 September 1629, Batavia’s Graveyard

And now it is time to truly ‘tidy up’ Batavia’s Graveyard, as Jeronimus might have put it. On this fine morning, Pelsaert and the skipper of the

Sardam

take some of their best men in the yacht’s yawl and longboat and make their way to Hayes’s Island. Pelsaert is both stunned and proud to see how well these good men and loyal Company employees have acquitted themselves, with their forts, their habitations, their water and food supplies so wonderfully well organised. Arming ten of Hayes’s men with musketry and swords, they row to Batavia’s Graveyard.

Upon that isle, the sight of the boats in the distance provokes instant consternation. For those few remaining Mutineers, the vision of the sun glinting off the forest of musketry and swords raised to the skies is nothing less than their death warrant.

‘Now the noose is around our necks and we are all dead men!’ they say to each other, thinking that the boats will no sooner land than the shooting will start, and yet that is not how it turns out. Pelsaert’s men simply come ashore and begin rounding up the Mutineers – as both parties know that any attempt at resistance from the Mutineers would be futile –

before binding them hand and foot

.

Two of Hayes’s men, however, have other things on their mind. All Jan Carstenz wants is to be reunited with his wife, Anneken Bosschieters. It has been well over three months since he was last able to embrace her, and from talking to those men who first escaped from this infernal isle he now knows only too well what she has been through.

Claas Jansz the Trumpeter is in the same position, having left his wife Tryntgien Fredericxs and her sister Zussie on Batavia’s Graveyard to go with Pelsaert on the longboat all the way to the Batavia citadel, and now he is back. He was first overjoyed to hear that Tryntgien and Zussie are still alive, and then appalled and outraged to hear what has occurred.

And here is Trynnie now. Her eyes having searched for her husband’s from the moment the boat appeared on the water, just as he has been looking for her, she runs up to Claas and embraces him as soon as he steps ashore. Lost in that impact between utter desolation and wild jubilation, where no words can even begin to express their feelings, where both know that for the rest of their lives they will remember this moment, neither speaks.

Just a small way over, Jan Carstenz is lost in a similarly troubled embrace with Anneken Bosschieters. For a long time, there are no words, until slowly, mumblingly, they begin to speak . . . They are words of neither explanation nor expiation – just small words, the bare beginnings of a very long and difficult dialogue.

In the meantime, Pelsaert is pursuing his own private passion. It is obvious from the first which of the tents must have been Jeronimus’s – the grand one – and Pelsaert makes straight for it. He sees Lucretia emerging from the tent at the same instant as she sees him, giving them both a start. For the barest moment, they pause, then Pelsaert rushes the last few steps towards her, taking her hand in his.

‘Commandeur,’ she says simply. ‘You have come. I knew you would.’

‘Of course, madam,’ he replies. ‘

I am glad to see you are alive

.’

And then he gets to the subject that has long been on his mind, and never more so than right now. ‘The Company’s money chests,’ he says. ‘Are they secure?’

Wordlessly, Lucretia simply waves her hand towards the entrance of the tent, and Pelsaert steps quickly forward to see for himself. Entering, he gasps. It is a near-perfect miniature recreation of his cabin, right down to the carpets on the floor, his old oak desk and the brass lanterns!

And there in one corner is his own, open chest of valuables, complete with the Great Cameo. Instantly crossing to it, Pelsaert quickly establishes that the cameo is undamaged and soon confirms that the four bags of jewels he left inside the case are all still there. It is something, at least. Not the dozen money chests he is hoping for, but certainly a good start.

Quickly opening all of the bags of jewels for further reassurance, Pelsaert ascertains that they are substantially intact.

And then . . .

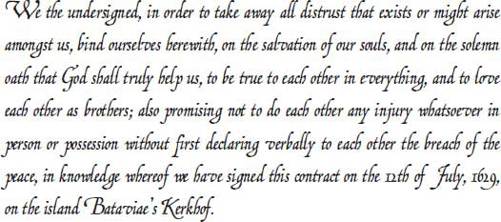

What is this? Right down at the bottom of the fourth bag of jewels, he finds three pieces of parchment, all with signatures at the bottom of a formal piece of writing. He begins to read the first one . . .

Click Here

And so on.

Quickly scanning all of the parchments, Pelsaert again realises that everything he has been told about Jeronimus is true, and here is the proof of that. The names of the signatories to these oaths – Coenraat van Huyssen, Jacop Pietersz, David Zevanck, Jan Hendricxsz, Mattys Beer, Jan Pelgrom – instantly give him a list of those whom it is most urgent to interrogate. The one name that leaps out at him, however, and takes his breath away for its sheer incongruity among what he now knows is a list of murderers, is that of Salomon Deschamps! How could this be? The most loyal Company servant he has ever come across, his colleague and friend for all of the last decade, has his name on the list as a

Mutineer

?

And so, there will be much work to do in these interrogations, but it is work that will allow Pelsaert to engage in what has always been his strong point in working for the Company. And that is the settling of accounts . . .

In the late afternoon of this day, the bulk of the Mutineers are placed on Seals’ Island under secure guard, where they can be sent for as they need to be interrogated – while Jeronimus, Jan Hendricxsz and a few other particularly dangerous ones are kept in the hole on the

Sardam

.

Pelsaert can now move on to the urgent matter of retrieving the dozen money chests submerged at the wreck site. It is almost more than he can bear to see the skeletal remains of the wreck first-hand, the once mighty ship now no more than a shattered remnant of what she was. Fully impaled atop the reef, a substantial part of the bulwark at the back of the vessel remains above the water, while lying in the shallows before it is a large piece of the bow of the ship, in which lies iron and brass pieces of cannon. Other bits of the wreck are clearly visible in deeper water, but at first glance it certainly does not look as though it is going to be a simple matter of sending down the divers to retrieve the missing chests.

Against that, upon returning disconsolately to Batavia’s Graveyard, Pelsaert is immensely comforted to hear from one of the Survivors, Chief Steward Reynder Hendricxsz, that a month earlier a day came so fine and calm that he was able to paddle a raft out to the wreck to go fishing, and he no sooner tried to spear his first fish than he hit a money chest by mistake!

It is heartening confirmation that the chests are still out there, and if this fellow could hit one with his spear, then it surely won’t be too hard to find more.

It is wet and dark in the prison hole this night – so wet and so dark it gives the illusion to the prisoners that they are totally isolated from the rest of the

Sardam

’s company and can thus speak frankly to each other in complete privacy.

Grunting with the hideous discomfort of the chains and their cramped position, Jeronimus questions the hulking Hendricxsz. ‘What happened? Why did you not take the little boat when you had the chance? Why did you not fire your muskets? Was your powder wet?’

Jan Hendricxsz replies, ‘If we could have fired a musket, we should have captured the boat for certain; but the gunpowder burned away three to four times from the touchhole.’

A groan of frustration comes from Jeronimus before he hisses, ‘

If you had used cunning

, you would easily have conquered while on the water, and then we should have been all right.’

In the darkness, it is the

Sardam

’s bosun, Jan Willemsz, one of Skipper Jacob Jacobsz’s best men, who overhears the conversation. He slips away to find someone who can write down what he has just heard . . .

19 September 1629, Batavia’s Graveyard

On this morning, Pelsaert is making notes once more on just who should be interrogated and what areas of inquiry should be focused on when his reverie is interrupted by the sound of shouting, coming from the direction of the beach . . .

The Mutineers on the

Sardam

are being brought ashore onto Batavia’s Graveyard for formal interrogations to begin.

‘

Mordenaars! Mordenaars!

Murderers! Murderers!’ The cries continue, as months of repressed loathing are now vented at the very men who have been the authors of their misery.

The prisoners’ progress on the island they once strutted over is now replaced by the irregular plod, stumble and shuffle of the vanquished. The irons restraining their arms behind their backs and the chains linking their ankles do not chafe for blood half as hard as the steely crowd gathered around them.

Most of the crowd’s anger is reserved for the first prisoner, a tall, dishevelled figure in the midst of the throng, none other than Jeronimus, still sporting his own tattered red uniform with the inordinate amount of gold trimming. Some of the angry even start throwing stones at him as they continue the cry. Pelsaert approaches to quell the crowd, and, as if by instinct, they part like the Red Sea.

Unable to freely move any limb, the apothecary pauses for a brief moment, casting an eye over the mob and the approaching

Commandeur

, one eyebrow raised as though seeing them all for the first time. Instinctively, a silence falls over the crowd. None dare answer that kiss of death – his gaze – as all stare down at their feet, lost in bitter memory. ‘How wonderful to see you all,’ he says blithely.

Wary by now of Jeronimus’s ability to turn to evil the hearts and minds of his fellow men, Pelsaert quickly nods to Wiebbe Hayes.

The prisoner is hurried on to the interrogation tent

, while the

Commandeur

turns away and walks off, without addressing a single word to Jeronimus.

The councils aboard all VOC vessels have the same power as a Dutch court on land – a system set up to ensure that all mutineers, murderers and so forth can be dealt with quickly on board, without having to run the risk of keeping them as prisoners for weeks on end.

The key to it is that no one can be executed without freely and fully confessing to his or her crime . . . Of course, rigorous application of torture to obtain the draft of said statement is more than permissible; it is common practice.

That very afternoon, Pelsaert convenes his council, composed of senior personnel from the

Sardam

and

Batavia

, and prepares to employ the prescribed method of securing the prisoners’ open confessions. It is time to begin.

The one-time macabre ruler of these islands approaches slowly, his leg chains clanking, his arms manacled tightly behind his back. A burly soldier from the

Sardam

holds him by one arm and brings him to stand before the Broad Council, as their judiciary is formally titled.

For a moment, no one speaks. The council gazes solemnly at Jeronimus, wondering that it is possible for just one man to be the author of so many evil actions, while Jeronimus merely stares balefully back at them.