Batavia (23 page)

Authors: Peter Fitzsimons

With his tongue poking through pursed lips, he looks along his sights to read the angle between the sun and the horizon and quickly does his other calculations.

He arrives at an estimation of their latitude

as 28 degrees 20 minutes south and marks it down on a piece of paper, which he then folds and tucks securely into his pocket.

7 June 1629, Batavia’s Graveyard

The large group of survivors gathered on the shores of Batavia’s Graveyard continue to stare balefully out across the expanse of ocean whence the longboat disappeared the day before. Despite the overwhelming evidence, they cling to the hope that there has been some mistake, that they are not to be left on their island without contact with either the skipper or the

Commandeur

.

Some are getting on with making the best of it. A stand-out in this regard is the soldier Wiebbe Hayes. Over on the western side of the island, he is busy with some of his fellow soldiers constructing rough shelters where they can gain respite from the belting wind. While, at the time of the voyage of the

Batavia

, Hayes has not been with the VOC long enough to rise high, still leadership comes naturally to him, and he has the even happier knack of being able to exercise it without getting others in the company of men offside.

It is he who is first to set up a small piece of sail in such a fashion that it will both provide shelter from the elements and collect whatever rain might fall,

funnelling it down into a barrel

– and all the others follow suit. It is also Hayes who organises the other soldiers to begin a systematic search for water on the island, digging everywhere. No matter that there are no early signs of success in this venture, he insists they all keep at it.

7 June 1629, High Islands

For Francisco Pelsaert, Ariaen Jacobsz and those with them, it is clearly time for . . . a committee meeting. There is simply no point in returning to the ship’s company upon the two islands to tell them that there is no water. And it is equally obvious to all that their best hope is to get to

het Zuidland

, which – if they are indeed on the Abrolhos – must lie only half a day’s sailing to their east, the coast to the north having been partially charted by Hartog a decade earlier. And, if still they could find no water there, then they should sail without delay to Batavia, to inform the authorities, with God’s grace, of their sad, unheard of, disastrous misfortune.

There is no dissension – for the only alternative is to return to the madness of the islands – so Pelsaert reluctantly gives the order for the preparations for the long journey ahead to begin. The three carpenters they have with them on the longboat busy themselves by starting to build strakes to lift the gunwale of their craft, to make allowance for the extra weight they will be carrying and render their vessel more secure against the open sea. Taking the planks that were thrown over to them from the stricken

Batavia

, they bring them close to the fire and bend them into the required shape before carefully nailing them into place on the vertical frame of the boat, which has been lengthened for the purpose. Thereafter, they use their caulking hammers and – in the absence of their favoured horsehair and pitch – apply torn pieces of cloth to start to properly seal it.

And then, suddenly, a shout goes up. A boat is coming their way! It is, of course, the only boat it could be, the yawl. In it are Third Steersman Gillis Fransz – known to the other sailors by his nickname of

‘Halffwaack’

, Half-Awake, for his ever-sleepy, relaxed attitude – and ten other sailors, one of whom has brought his wife and their two-month-old baby with them. Pelsaert’s previous orders to Fransz to go to the wreck notwithstanding, they, too, are now in search of fresh water and have arrived on this shore by virtue of exactly the same reasoning that has propelled Pelsaert, Jacobsz and their men. Though happy to see the people of the longboat,

Halffwaack

and his men are devastated to realise from all the diggings that the search for water has been fruitless.

Fransz reports to Pelsaert and Jacobsz that it is still impossible to get to the wreck and that the situation back on Batavia’s Graveyard – which they could see and hear as they passed – looks to be grim and getting grimmer. He says that chaos reigns and the last of the survivors’ water on the island also appears to have gone. Fransz and his men also refused to land.

The earnest request of Gillis Fransz now is that he and everyone else in the yawl be allowed to accompany the expedition to

het Zuidland

, which makes a certain amount of sense. Among other things, Fransz is an expert sailor, as are his men, and his presence on the boat will increase their chances of success.

After discussion, just as the sun goes down, it is decided that Fransz and his ten men – plus the two women and baby they also have with them – will all travel in the longboat while they tow the yawl behind them, against the possibility they will need the lighter craft to get through difficult surf in search of water. It will be as tight as soused herring in a barrel, as there will be 48 of them in a boat designed to carry just 35, but a quick test, when they all pile in, shows that it is just possible for the boat to remain stable provided no one farts.

8 June 1629, High Islands

On this sparkling morning, from first light, the carpenters continue to work feverishly to make sure the extra strakes to heighten the gunwale are sealed and secure, while the sailors mostly simply watch and wait. One who stands a little aside, however, in an agony of indecision, is Chief Trumpeter Claas Jansz, who accompanied Pelsaert and Jacobsz to these islands on the reckoning they would be away for no longer than a day. He has left his wife, Tryntgien Fredericxs, back on Batavia’s Graveyard and she is expecting him to return! But everything has changed so rapidly. There will be no return to Batavia’s Graveyard in the near future. And he has no means of getting back to Tryntgien. What can he do? Stay behind, alone on this seemingly waterless island? Finally, he comes to the conclusion that he has no choice. He will have to go with them and trust that Tryntgien will be all right.

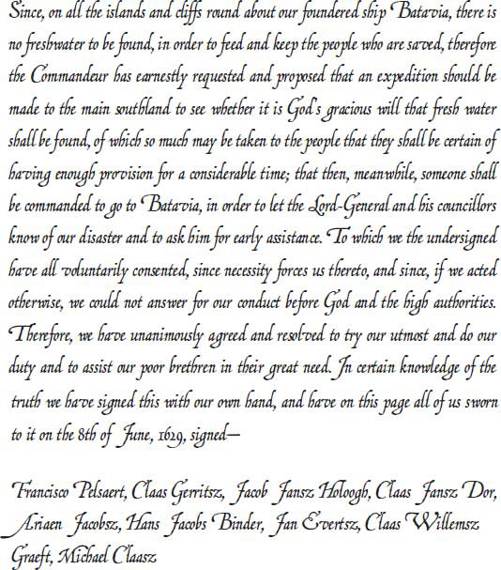

Before finally leaving, Pelsaert is more troubled than ever. The act of abandoning the 200-odd souls on the islands is such a dire, devastating thing to do that – against the day they will have to justify their actions to the Company – the

Commandeur

insists that everyone takes collective responsibility for the decision and signs a document to that effect. Carefully, he draws up the said document and then reads it out to the assembled company, before asking all the men to sign, which they do readily – at least those who are capable of writing more than an X. After all, there really is no alternative. To refuse is to make the case for being left behind on these waterless islands, and that would be an all but certain death warrant.

In order of precedence, thus, they sign the piece of parchment that Commandeur Pelsaert offers them:

Click Here

It is done. Pelsaert carefully folds the parchment and puts it in his inside coat pocket. And, with that, all 48 people climb into the longboat and set off in the name of the Lord, into the open sea and towards the mid-morning sun, steering north-east. Pelsaert most certainly does not approve of the fact that Jacobsz has brought his whore, Zwaantje, with him but is powerless to stop it. Their endeavour, which may well see them make an attempt to reach Batavia across 2000 miles of open sea, is one that will require extraordinary seamanship. This puts it squarely in the domain of Jacobsz’s responsibility, and if the skipper wishes to bring Zwaantje then so it must be. In any case, now that the frantic activity of the last few days has subsided, Pelsaert is beginning to return to his normal state – feeling as sick as

two

dogs – and knows that he simply does not have the strength to struggle with Jacobsz on this one.

So Pelsaert leaves with a heavy heart, still beset by cruel doubts as to whether they are doing the right thing. His most earnest hope is that once they reach the coast of

het Zuidland

, they can find a place with plentiful game and water. If they do, it might even be possible to lighten the load and drop off many of those currently aboard the longboat, then return to the Abrolhos and ferry the remaining survivors there. If all could be secured there, he and Jacobsz, with far fewer men than they have with them now, would be able to continue up the coast and on to Batavia to secure a rescue ship.

For his part, Jacobsz is beset by no such doubts as they leave. It is clearly the best thing for him and Zwaantje personally, as it maximises their chances of survival, and he also feels it is the best chance for the ship’s company back on the small islands. Instinctively, he pats the small piece of paper in the pocket of his pants, where he has written down the latitude of where the wreck is to be found.

8 June 1629, Batavia’s Graveyard

A sail!

At least the top of one, right on the far horizon to their north. The 200-odd souls gathered on Batavia’s Graveyard can see that the

Commandeur’s

longboat, which brushed so close to them two days ago before heading to the High Islands, is once again on the water. Surely, this time, the

Commandeur

will return to them and start to make things right. Surely, the sail, now moving from west to east, will soon veer to starboard and loom larger on the horizon, as the

Commandeur

makes his way towards them in the longboat now laden with full barrels of water and perhaps freshly killed meat from whatever fauna they have found on those islands.

To their horror, however, the sail keeps getting smaller, not bigger. It is moving away from them. The

Commandeur

really

is

abandoning them! The disgust of the people is palpable, their outrage incandescent. It is

traitorous

, so traitorous that from this day forth the smaller island that the

Commandeur

and his fellow traitors had spent their first two nights on is referred to as

Verraders’ Eylandt

, Traitors’ Island.

8 June 1629, in the longboat

Aboard the longboat itself at this time, the worry is all-pervading. Even with as shallow a draught as they have, it is a major exercise to get away from the shallows and into water deep enough that they may sail freely. And, even then, there are myriad reefs and shallows ahead that they must negotiate.

And yet, after an hour or so, they are finally, truly on their way, in water deep enough that they can set a full sail to the wind. Their longboat begins to buck forward, eager to be free on the open ocean, and they head north-east at a good clip. Looking back, Pelsaert is stunned, and momentarily disconcerted, to see how quickly all trace of the extremely low islands have sunk beneath the waves. They were there, a small brown patch marking the point where the blues of the sky and the sea met, and then they were gone.

In the early afternoon, in a latitude of 28 degrees 13 minutes south, and in 28 to 30 fathoms of water, with the westerly wind behind them, Pelsaert, Jacobsz and the others in the longboat sight the coast of

het Zuidland

to their north-east.

At first look, it does not seem hopeful. Carefully continuing on their course towards it, they are appalled to see what appears to be an unending line of massive breakers pounding into tall, stark cliffs – breakers so huge and strong that they surely make the cliffs tremble. There appears to be no break in those cliffs to indicate a harbour, a river or a needed refuge of any description from the forbidding wall that confronts them. And not the smallest sign of a beach.

What can they do? There is only one option: steer away from the land for safety’s sake, continue sailing along the coastline to the north and hope that on the morrow the shoreline will have changed and they will find water.

It proves to be a very difficult night. It was one thing to be packed so tightly into a boat designed to carry far fewer while it was still daytime, but it is quite another to try to sleep in it at night. Finding space to lie down is out of the question, so the best they can all do is to lean into each other, with the head of one man against the back of the man in front, until they drop into an exhausted stupor, punctuated only by the regular sounds of the baby crying. At around midnight, the sound of crashing breakers tells them that they are once again too close to the coast, and they haul off once more.

9 June 1629, in the longboat

At dawn, they find themselves about three miles from the shore, in a strong north-westerly wind that brings some blessed rain with it. At its first drops, all of them turn their faces skywards and hold their hands outstretched as they thank providence, even as they take in the precious drops falling on their tongues.

But the coast to their starboard looks every bit as unwelcoming as it did the evening before. Running south-east to north-west, it is bare and rocky, with no trees visible atop the sheer cliffs, cliffs that the more experienced sailors among them reckon to be perhaps twice as high as those at Dover, at nearly 750 feet. And yet, whereas when facing the white cliffs of Dover, one could see green hills in the distance, and even the spires of churches and the softly, slowly curling friendly smoke from hundreds of scattered dwellings . . . here there is nothing! No greenery, just arid red, ‘

a seemingly dry cursed country

without foliage or grass’, as Pelsaert later describes it. Not the slightest sign of any human structure. And

no

sign of any human activity. It seems quite likely that the place is uninhabitable, but still they have not given up hope of finding a people living in these parts who could give them some succour, who at least could demonstrate that it

is

possible to survive in such a land. As they continue up the coast, though, hour by hour, day by day, they see nothing.