Batavia (2 page)

Authors: Peter Fitzsimons

In this case, however, the challenge was different and, for me, intellectually absorbing. For, nearly 400 years on, only a few scattered pieces of that original picture have survived – about 500 by my count. Thus, the challenge is to be able to have a strong-enough grasp of what

is

known and do enough research on both the time and the people involved to give one the necessary confidence to fashion another 500 pieces that fit, without distorting the true picture.

In trying to make those pieces as authentic as possible, I have been greatly helped by Dutch experts in their field: Diederick Wildeman, curator of navigation and library collections of Amsterdam’s Scheepvaart Museum; Vibeke Roeper, of the Cultureel Erfgoed Noord-Holland; Jan Piet Puype, formerly of the Leger Museum, the chief expert on guns in the Dutch Republic during this period of history; Jaap van der Veen of Amsterdam’s Rembrandt House; Lennart Bes of the National Archives in The Hague; Aryan Klein, project manager of the

Batavia Werf

, shipyard, in Lelystad; and, most particularly, Ab Hoving of the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam, who was a notably wonderful source of fine detail on seventeenth-century Dutch maritime history.

In Australia, author Paquita Boston gave me greatly valued advice on ancient Aboriginal culture, and I was constantly calling on Helen Wilder’s skills in the Dutch language. I drew on the expertise of Stephen Jackson and Alex Whitworth when it came to the conditions of the various oceans, and on all matters of medical history my dear friend Dr Michael Cooper was a fount of information. Now, if all of these experts agreed on every detail of what is historically correct, my life would have been a lot easier. As it was, when they disagreed – and they frequently did – on just which way the nautical world worked 400 years ago, I had to make a decision.

My aim has been to be able to confidently say that, ‘While many of the original pieces from this puzzle have not survived, based on the shape of all the surviving pieces, it almost certainly looked just like this.’ By way of example, though there is no record in the primary documents of the

Batavia

’s surgeons employing the medical methods I describe in this book, expert research informs me this is the way it was done at that time. And, though there is little record of the precise words that Pelsaert spoke to Jeronimus when they reached the Abrolhos, the dialogue I have constructed is entirely consistent with both their established characters and the other bits of their dialogue that have survived. On several occasions, such as when they left Texel and arrived at Table Bay, I have adapted detailed dialogue from roughly contemporaneous accounts to illustrate the likely scenarios aboard the

Batavia

.

And yet, if I have taken some latitude, it is under strict conditions. From 1617 on, when Dutch ships were rounding the Cape of Good Hope on their way to the East Indies, they were instructed to keep between the latitudes of 36 and 42 degrees south as they headed east – the chosen

karrespoor

, cart-track, across the ocean. Similarly, I have framed this book so as to keep between the tight latitudes of the historical record, while still affording myself a little room to manoeuvre within those parameters.

This approach will likely attract criticism. So be it. The important thing for me is that all the key events described in this book are documented in the primary sources, all the machinations and dynamics between the protagonists laid down in black and white. Wherever possible, time and time again I have returned to and referenced Pelsaert’s Journal, bearing in mind that it is a one-eyed account of events by a man under enormous pressure.

A good 113 years on, I have accepted Willem Siebenhaar’s challenge to put permanent life into the story’s dry bones. I have been aided by the fact that far more has now become known of the saga than in his time, and even in the time since Henrietta Drake-Brockman’s fictional account

The Wicked and the Fair

was published in 1957.

In his review, Mike Dash criticised Drake-Brockman’s non-fiction take on the subject,

Voyage to Disaster

, on the grounds that her ‘book has no real narrative and fails, really, to convey the unprecedented drama of the

Batavia

’s wreck and the appalling events that followed it . . .

It is not a narrative history

, nor an easy book to read.’

I make no such criticism of his great book but do note that my intention is to try to go one step further. That is, I want to accurately ‘convey the unprecedented drama of the

Batavia

’s wreck’ by making it read like a novel, while not limiting myself to only the few precise details of the story that have survived the four centuries – most particularly when even those primary documents are sometimes contradictory as to what happened. I have included notes at the end of the book indicating where I have departed significantly from the documentary evidence along with my justification in so doing.

While struggling to work out how best to tell the

Batavia

story, I was fascinated to note that I was not alone, and that similar struggles have been going on for 350 years. In a closing note to the first edition of the

Ongeluckige Voyagie

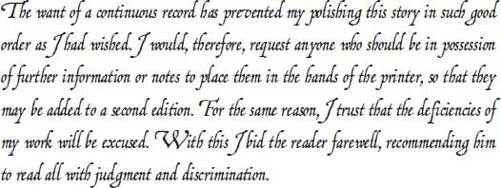

in 1647, Dutch publisher Jan Jansz wrote:

Exactly.

In the course of writing

Batavia

, I have travelled to India to see the real spice markets that are still in operation, to the Abrolhos Islands off the coast of Western Australia, to the remains of the citadel of Batavia, which can still be seen in the old city of Jakarta, and, of course, to Amsterdam, from where the ship

Batavia

set out, and The Hague, where the records of her voyage are kept.

In the Shipwreck Galleries at the Western Australian Museum in Fremantle, I devoured the wonderful

Batavia

exhibit, including the skeleton and facade of the shipwreck, just as I loved the museum in Geraldton with its own

Batavia

exhibit. Those displays are masterpieces of recovery, conservation and reconstruction, due in no small part to the hard work put in by the museums’ staff, led by Dr Jeremy Green, who in 2007 won the Rhys Jones Medal in acknowledgement of his pioneering work in the development of maritime archaeology in Australia. The Western Australian Museum could not have been more helpful to me, particularly staff members Dr Michael McCarthy and Patrick Baker, the latter supplying some excellent images for the book.

For her help in all things to do with the form and texture of the book, I offer my deep appreciation to my treasured colleague at the

Sydney Morning Herald

Harriet Veitch, just as I do to my long-time researcher Sonja Goernitz, who was a great help across the board. Let me particularly acknowledge the work of my dear friend, and principal research editor on this book, Henry Barrkman. I have never worked as closely with anyone in the writing of a book, and, by its end, he was more familiar with the primary documents than I was. He was a constant sounding board as to how I might extrapolate from them, how the principal characters interacted, what the most likely chronology was for various events, and, when information conflicted, which account was the most likely. My debt to him is enormous.

I thank all at Random House, particularly Margie Seale, Nikki Christer and Alison Urquhart, for backing the project from the first, and my editor, Kevin O’Brien, for his meticulous approach and keen dedication.

Peter FitzSimons

Neutral Bay

Author’s Note

References

As described in the Preface, in telling this story I have strictly adhered to the two primary documents: Pelsaert’s Journal and the Predikant’s Letter. Both have been thoroughly referenced throughout and, together with my secondary sources, appear at the back of the book in the Notes and References section. Additionally, I have included comments in this Notes and References section to not only indicate where I may have taken liberties in departing from the primary texts – for example, in the creation of dialogue or the extrapolation of events from evidence given in those texts – but also, and I believe uniquely, provide justification for so doing. I believe all such departures are soundly underpinned by the documentary evidence and/or information from expert consultants and will add to the reader’s overall enjoyment without significantly compromising historical accuracy.

Pelsaert’s Journal

Frequently, a reference to Pelsaert’s Journal will postdate a section’s dateline, or a sequence of references to the Journal will appear chronologically out of step. This is because Pelsaert’s Journal is not a strict, day-by-day account but contains many retrospective references and also narrates certain events and testimonies in a different order from that in which they occurred.

Naming conventions

Writing this book put me on intimate terms with the difficulties of Dutch nomenclature. Because surnames did not exist in the Dutch Republic in the early part of the seventeenth century, a man’s full name comprised his first name followed by a ‘patronymic’, derived from the first name of his father with the letters ‘

zoon

’, son of, added to the end to indicate descent. For example, ‘Claas Gerritszoon’ defined a man as Claas, Gerrit’s son, the ‘s’ being possessive. Because this ending was a bit of an eyeful, it was common practice to drop the ‘oon’ and abbreviate the patronymic, in this case to Gerritsz (although the ‘oon’ is always pronounced in spoken Dutch). Strictly speaking, a full point should be used after the ‘sz’ to highlight the abbreviation, but I have followed the example of those who have gone before me, such as Drake-Brockman, in omitting the punctuation mark in favour of ease of reading.

A man would never have been referred to by his patronymic alone, rather by either his title and first name, in this case Opperstuurman Claas, or simply his first name, Claas. But, to my twenty-first-century ear, referring to a rough sailor type as Opperstuurman Claas or simply Claas sounds less apt than the more manly-sounding patronymic Gerritsz. Also, using a person’s full name on each and every occasion is cumbersome and repetitive. Accordingly, although historically incorrect, when not giving a name in full I name men according to their shortened patronymic. The only real exception to this rule has been that of the central character Jeronimus Cornelisz, whom I have referred to mostly as simply Jeronimus, because that name and mode of address struck the right note in terms of personality.

The naming convention adopted in this book has presented problems, given the number of men in this story who have identical patronymics. In such cases, I have distinguished lesser characters by using their full names (title and first name), country of origin, or, where all else has failed, including the ‘oon’ ending in their patronymic.

A woman’s full name comprised her first name plus the patronymic ‘

dochter

’, daughter of. For example, Lucretia Jansdochter translates as Lucretia, daughter of Jans. The female patronymic was frequently abbreviated to ‘dr’. For all women, who are few enough in this book to avoid confusion through shared first names, when not including an abbreviated patronymic without the ‘dr’ – for example, Lucretia Jans – I have used solely their first names.

Measurements

I have avoided using both modern measurements, such as kilograms, kilometres and metres, and seventeenth-century Dutch measurements, such as a

mutsken

, equivalent to around a quarter of a pint, or

kannen

, equivalent to around one and three-quarter pints, and have instead used imperial measurements such as tons and miles, for ease of storytelling while still retaining an old-world feel.

INTRODUCTION

The Spice Trade

Jesus Christ is good, but trade is better.

Unofficial motto of the Dutch East India Company

Our story is set in a time of strangely overlapping cusps.

For it takes place as the era of exploration is gradually giving way to the age of colonialism. It is a time when, as one powerful empire is destroying itself through religious zealotry, another is rising fast through its own fervent embrace of a new creed: corporate power. It is at the end of an epoch when most people live their entire lives within 20 miles of their birthplace, and on the leading edge of an age when events on one side of the planet can have an impact on even the most far-flung, seemingly inconsequential crag of rock on the other. And such is the strange symmetry of this story that even the particular crag of rock that will feature in these pages, the Abrolhos Archipelago, is two things at once: the southernmost group of islands in the world defended by coral reefs and the northernmost group of islands in the southern hemisphere populated by sea lions.

And it all comes together in this saga, which, by any measure, is one of the most stunning stories the world has known. It combines in just the one tale such momentous elements as the world’s first corporation, the brutality of colonisation, the battle of good versus evil, the derring-do of seafaring adventure, mutiny, love, lust, bloodlust, greed, treasure, criminality, a reign of terror, murders most foul, sexual slavery, natural nobility, survival, retribution, rescue, first contact with native peoples and so much more.