Baseball's Hall of Fame or Hall of Shame (39 page)

Piazza first began to establish himself as one of the game’s most dominant hitters in 1993, with the Los Angeles Dodgers. In winning N.L. Rookie of the Year honors, he hit 35 home runs, knocked in 112 runs, and batted .318. Piazza continued his assault on National League pitching the next nine years, before injuries and age began to take their toll on him during the 2003 season. Prior to that, though, he hit more than 30 home runs in nine of his first ten seasons, twice hitting as many as 40 long balls. During that period, he also drove in more than 100 runs six times and batted over .300 nine times, topping the .320 mark on five separate occasions.

Piazza had perhaps his finest season for the Dodgers in 1997. That year, he hit 40 home runs, knocked in 124 runs, and batted .362. He had another great season for the Mets in 1999, when he hit 40 homers and knocked in 124 runs, while batting .303.

During the first 10 years of his career, Piazza was the National League’s top catcher, and, in many of those seasons, the very best in baseball. He was clearly the game’s top receiver from 1993 to 1998, and, once again, in 2001. Rivaled only by Ivan Rodriguez for much of his career, it would be difficult to classify Piazza as the complete player that Rodriguez was at his peak. But the latter never swung as potent a bat as Piazza, who would have to be regarded as this generation’s top receiver as a result. Piazza was selected to the N.L. All-Star Team in each of his first ten seasons, and also finished in the top ten in the league MVP voting seven times, making it into the top five on four separate occasions.

Piazza’s defensive shortcomings may dissuade some of the members of the BBWAA from electing him to the Hall of Fame in his first year of eligibility. However, there is little doubt that his hitting prowess will earn him a spot in Cooperstown shortly thereafter.

Greg Maddux

As one of the top two or three pitchers of his generation, Greg Maddux is certain to gain admittance to Cooperstown in his first year of eligibility. Although he was never as overpowering as either Roger Clemens or Randy Johnson, Maddux was arguably the most effective, and, certainly, the most consistent pitcher of his era.

In 2008, Maddux completed his 23rd season in the big leagues, and his 22nd as a regular member of his team’s starting rotation. For 17 consecutive seasons, between 1988 and 2004, he won at least 15 games, establishing a new major league record. In so doing, he also surpassed 300 victories, becoming one of the last of a vanishing breed.

Relying primarily on outstanding ball movement and exceptional control, Maddux was the National League’s top pitcher, and one of the two or three best in baseball, for much of the 1990s. In the nine seasons from 1992 to 2000, he won at least 18 games seven times, finished with an ERA under 2.50 six times, compiled an overall won-lost record of 165-71, and won four Cy Young Awards. He is one of only two pitchers in baseball history to win as many as four consecutive Cy Young Awards (Randy Johnson is the other). Maddux won the award each season, from 1992 to 1995. Here are his numbers from those four years:

1992:

20 wins, 11 losses; 2.18 ERA

1993:

20 wins, 10 losses; 2.36 ERA

1994:

16 wins, 6 losses; 1.56 ERA

1995:

19 wins, 2 losses; 1.63 ERA

In each of those years, Maddux was not only the best pitcher in the National League, but the best in baseball. Furthermore, Maddux would have to be included with Roger Clemens, Randy Johnson, and Pedro Martinez in any discussions involving the greatest pitcher of the last 25 years. He led the National League in wins three times, ERA four times, shutouts five times, complete games three times, and innings pitched five times. He won at least 17 games ten times and finished with an ERA below 3.00 nine times, twice allowing less than two earned runs per contest. Maddux finished in the top five in the league MVP voting twice, and placed in the top five in the Cy Young voting a total of nine times. He was selected to the All-Star team eight times and was awarded 18 Gold Gloves for his fielding excellence. Upon his retirement at the conclusion of the 2008 season, Maddux’s career won-lost record stood at 355-227, and his ERA was 3.16. Those 355 victories are the most by any pitcher whose career began after 1950, and place him second to only Warren Spahn among hurlers who began pitching after 1920.

Recently Retired Borderline Candidates

There are eight other players with some extremely impressive credentials whose careers ended within the last six or seven years. It will be interesting to see how these men fare in the balloting in the upcoming elections. The feeling here is that four of the eight players should be considered stronger candidates than the other four, and that only those four men should be seriously considered for enshrinement at Cooperstown.

Following is a list of these borderline candidates:

Fred McGriff

Craig Biggio

Barry Larkin

Tim Raines

Albert Belle

Juan Gonzalez

Larry Walker

Mike Mussina

Fred McGriff

Fred McGriff came within seven home runs of testing the theory that 500 home runs are no longer enough to guarantee election into Cooperstown. With 493 career homers, McGriff was a dangerous hitter and a very solid player for most of his career. But he was never a truly dominant one.

Playing in an era when lofty home run totals became rather commonplace, McGriff never hit 40 homers, and scored more than 100 runs only twice. He led his league in home runs twice, but never finished first in any other offensive category. In addition, he was selected to the All-Star Team only five times—not a particularly high number for a potential Hall of Famer—and he was never regarded as the best first baseman in baseball. In fact, in only the 1993 season could it legitimately be said that McGriff was even the best first baseman in his own league. That year, splitting time between the San Diego Padres and Atlanta Braves, he hit 37 home runs, knocked in 111 runs, scored another 111, and batted .290.

Nevertheless, McGriff’s supporters will point to some rather impressive figures when he becomes eligible for induction in 2010. He hit more than 30 homers ten times, drove in more than 100 runs eight times, batted over .300 four times, and finished in the top ten in his league’s MVP voting six times. In addition to his 493 home runs, he finished with 1,550 runs batted in, 1,349 runs scored, 2,490 hits, a .284 batting average, and a .377 on-base percentage.

With the fairly liberal approach many members of the BBWAA seem to take towards the elections, there is a strong possibility that McGriff will eventually be voted into Cooperstown. However, the feeling here is that he probably falls just a bit short of being a worthy Hall of Famer.

Craig Biggio

In this era of free agency, Craig Biggio was an oddity in that he spent his entire career with one team. Originally a catcher when he first came up to the Astros in 1988, Biggio spent the majority of his 20-year career with Houston as a second baseman, becoming one of the game’s best players at that position for virtually all of the 1990s. After making the National League All-Star Team as a catcher in 1991, Biggio was shifted to second base prior to the start of the 1992 season. Between 1992 and 2002, Biggio made six appearances on the All-Star Team, and won four Gold Gloves and four Silver Sluggers.

Biggio had his five most productive seasons from 1995 to 1999, hitting more than 20 homers in three of those years, knocking in at least 73 runs and scoring at least 113 times every year, and batting over .300 three times. His two finest seasons were 1997 and 1998. In 1997, he hit 22 homers, drove in 81 runs, scored 146 others, stole 47 bases, and batted .309. Biggio followed that up the next year by hitting 20 homers, knocking in 88 runs, scoring another 123, stealing 50 bases, collecting 210 hits, 51 of which were doubles, and batting a career-high .325. Even though Jeff Kent knocked in more runs both seasons, Biggio was arguably the best all-around second baseman in baseball in each of those years. He may well have been the best second sacker in the game in 1995 as well. That year, he hit 22 home runs, drove in 77 runs, scored 123 others, and batted .302, while committing only 10 errors in the field.

In all, Biggio hit more than 20 homers eight times, knocked in more than 75 runs four times, scored more than 100 runs eight times, batted over .300 four times, collected more than 50 doubles twice, and stole more than 30 bases five times. He led the National League in runs scored twice, doubles three times, and stolen bases once. Biggio finished in the top ten in the league MVP voting three times, making it into the top five twice.

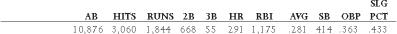

Upon his retirement at the conclusion of the 2007 campaign, Biggio’s stat-line read thusly:

Biggio’s numbers are better than the statistics compiled by more than half of the 19 second basemen currently in the Hall of Fame. They are comparable to the overall figures posted by legitimate members such as Frankie Frisch and Ryne Sandberg, and are somewhat better than those compiled by borderline inductees such as Billy Herman, Bobby Doerr, Red Schoendist, and Nellie Fox. And they are vastly superior to the numbers posted by unworthy members such as Johnny Evers and Bill Mazeroski. Thus, a strong case could certainly be made on Biggio’s behalf. He had six or seven truly exceptional years, and was one of the top two or three second baseman of his generation.

Yet, Biggio was not generally considered to be among the very best players of his era. It must also be considered that his figures were compiled during a hitter’s era, and that, during the last several seasons of his career, after the Astros moved out of the Astrodome, Biggio played in a ballpark that was a hitter’s paradise. As a result, in spite of the outstanding offensive numbers he posted for a second baseman, Biggio should be viewed as a somewhat borderline candidate. Nevertheless, his 3,000 hits are likely to gain him admittance to Cooperstown in his first few years of eligibility.

Barry Larkin

Though overshadowed for much of his career by the great Ozzie Smith, Barry Larkin was the National League’s finest all-around shortstop for the better part of his 19-year major league career. While Smith received more publicity in many of those seasons, Larkin was the league’s best shortstop for the entire decade of the 1990s. Over that ten-year period, he batted over .300 seven times, hit more than 20 homers twice, scored more than 100 runs twice, stole more than 30 bases four times, and developed into one of the finest defensive shortstops in baseball.

The greatest shortstop in Cincinnati Reds history, Larkin was named the National League’s Most Valuable Player in 1995, even though he posted relatively modest numbers that season, hitting only 15 home runs, knocking in just 66 runs, and scoring only 98 others, while batting .319 and stealing 51 bases. The following year was actually Larkin’s best, with him establishing career highs in home runs (33), runs batted in (89), and runs scored (117), while batting .298. In all, Larkin finished in double-digits in home runs nine times, batted over .300 nine times, and stole more than 30 bases five times. He also won three Gold Glove Awards, finished in the top ten in the league MVP voting twice, and was selected to 12 All-Star teams. He ended his career with 198 home runs, 960 runs batted in, 1,329 runs scored, 2,340 base hits, 379 stolen bases, and a batting average of .295. That .295 average is the third highest of any shortstop with more than 5,000 at-bats in the last 50 years.

However, Larkin was never thought of as being a

great

player. He never led his league in any offensive category, was never considered to be one of the very best players in the game, and was never even rated as the best shortstop in baseball. Furthermore, in only seven of his 19 seasons with the Reds did Larkin appear in as many as 140 games and compile as many as 500 official at-bats.

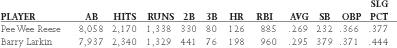

Nevertheless, Larkin was a fine player for a very long time, and his statistics compare quite favorably to several shortstops already in the Hall of Fame. Of the 22 shortstops who have been inducted thus far, 20 of whom played in the major leagues, only three (Ernie Banks, Cal Ripken Jr., and Robin Yount) hit more home runs, only six scored more runs, only four stole more bases, and only six finished with a higher lifetime batting average. Although it must be remembered that the two men competed during different eras, Larkin’s offensive statistics are slightly better than those of Pee Wee Reese.