Baseball's Hall of Fame or Hall of Shame (22 page)

These numbers not only illustrate that Oliva was an extremely consistent hitter, but they also indicate that he didn’t have the “home-field advantage” that Puckett had throughout his career. Thus, it could be argued that Oliva, who was also a good outfielder and a fine baserunner, was actually a better player than Puckett. Yet, for some reason, Puckett was elected to the Hall of Fame in his first year of eligibility while both Oliva and Mattingly have received only minimal support. Perhaps the reason for this lies in the fact that Puckett played on two world championship teams while neither Oliva nor Mattingly was fortunate enough to have done so. Furthermore, Puckett was an outstanding player right to the end, while Oliva and Mattingly both experienced a considerable drop-off in performance after their early years of dominance. Whatever the reason, though, it is something of an injustice that Puckett was ushered into the Hall with such alacrity while the other two men remain on the outside looking in. Once again, this is not to suggest that Oliva and Mattingly should be elected, although, in truth, neither man would be a particularly bad choice. However, the thing I am suggesting is that perhaps Puckett’s qualifications should have been considered a little more carefully before he was voted in. In any case, he should be viewed more as a borderline Hall of Famer than as an automatic, first-time selection.

Hack Wilson

During his 12-year major league career, Hack Wilson played for the Giants, Cubs, Dodgers, and Phillies. It was with the Cubs that he had his finest seasons, leading the National League in home runs four times, and in runs batted in and slugging percentage twice each between 1926 and 1930. His 1929 and 1930 seasons were both superb, as he hit 39 home runs, drove in 159 runs, scored another 135, and batted .345 in the first of those years, and hit 56 homers, knocked in an all-time record 191 runs, scored 146 others, and batted .356 in the second. Over the course of his career, Wilson hit more than 30 homers four times, drove in more than 100 runs six times, batted over .300 five times, and scored more than 100 runs three times.

However, Wilson was a full-time player for only six seasons, compiling as many as 400 at-bats only those six times. He had those tremendous 1929 and 1930 campaigns, along with another four very good ones. But he failed to hit more than 13 home runs, knock in more than 61 runs, score more than 66 runs, or bat any higher than .295 in any other year. In addition, Wilson, with his squatty frame and beer-barrel chest (he stood only 5'6" and weighed over 200 pounds), was not particularly fleet afoot, and was generally considered to be a below-average outfielder.

Using our Hall of Fame criteria, Wilson was never considered to be the best player in baseball, but it could be said that, in his two finest seasons, he was ranked among the top two or three players in the National League (along with Chuck Klein and Mel Ott in 1929, and Klein and Bill Terry in 1930). He also would have been ranked among the game’s elite players those two seasons. It could also be argued that he was the best centerfielder in the National League from 1926 to 1930. However, Wilson certainly was not one of the ten best centerfielders in the history of the game, nor was he the best player in the game at his position for more than two seasons.

Wilson finished in the top 10 in the MVP voting four times, even though the award was not presented in 1930, his greatest season. However, he never finished any higher than fifth in the balloting. We have already seen that he led his league in some major offensive category eight times during his career. He did help the Cubs to the National League pennant in 1929, but, if anything, he was probably not as good as his statistics indicate. He was not a good defensive player or baserunner, and he had a drinking problem and a surly disposition that made him unpopular with most of his teammates, and that eventually shortened his career.

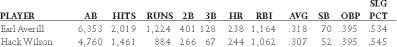

Thus, overall, it would seem that Wilson does no better than average on the Hall of Fame criteria board. Let’s look at his career numbers next to those of Earl Averill, a legitimate Hall of Famer whose career overlapped with Wilson’s:

Due to the relative brevity of both players’ careers, the numbers they posted are not particularly overwhelming. In most categories, they are actually fairly similar, although Averill does have a sizeable lead in runs scored, doubles, and triples. However, Averill was a better outfielder and a more complete player. If he is viewed as being a legitimate Hall of Famer, but not an obvious choice, how should Wilson be viewed? That really all depends on how liberal approach one wishes to take in considering potential Hall of Fame candidates. While Wilson was an outstanding player for a few seasons, he truly did not have a Hall of Fame type career. Nor, with the exception of two years, was he ever a

great

player. The feeling here is that the Veterans Committee’s 1979 selection of Wilson was not a particularly bad one, but was one that probably should not have been made.

Richie Ashburn

It was Richie Ashburn’s fate to play in the major leagues during an era in which some of the greatest centerfielders in baseball history were performing for other teams. His first year with the Philadelphia Phillies was 1948, when a man named DiMaggio was still playing centerfield for the Yankees. One year earlier, Duke Snider was called up by the Dodgers, and three years later, both Willie Mays and Mickey Mantle arrived in the big leagues. As a result, Ashburn was relegated to second-tier status among major league centerfielders throughout most of his career, playing in the shadow of these all-time greats. However, he was a fine player whose career was certainly deserving of Hall of Fame consideration. Let’s take a look at his qualifications.

Ashburn was perhaps the finest leadoff hitter of his time, collecting 2,574 hits and scoring 1,322 runs during a career that saw him finish with a .308 batting average and an outstanding .397 on-base percentage. He won two batting titles and also led the National League in on-base percentage and bases on balls four times each, hits three times, triples twice, and stolen bases once. Although he scored more than 100 runs only twice, he topped the 90-mark seven other times. Ashburn batted over .300 in nine of his 15 seasons, topping .330 five times. He collected more than 200 hits three times, stole more than 30 bases twice, and finished in double-digits in triples three times. Ashburn was selected to the All-Star Team five times and was considered to be one of the finest defensive outfielders of his time.

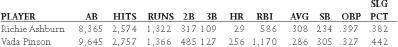

However, due to the presence of Snider and Mays, he was never considered to be the best centerfielder in the National League. Ashburn also finished in the top 10 in the MVP voting only twice during his career. In addition, his overall statistics are actually less impressive than those of Vada Pinson, whose career spanned the entire 1960s and much of the 1970s—less of a hitter’s era than when Ashburn played. Here are the numbers of both players:

While Ashburn finished with a higher batting average and a much higher on-base percentage, Pinson was well ahead in virtually every other offensive category. He hit almost ten times as many home runs as Ashburn and knocked in twice as many runs. Pinson hit more than 20 homers seven times, drove in more than 100 runs twice, scored more than 100 runs four times, batted over .300 four times, and stole more than 20 bases nine times. In addition, he was an excellent outfielder with a much stronger throwing arm than Ashburn. Yet he received only minimal support during his eligibility period.

Why, then, was Ashburn elected instead of Pinson? Ashburn was very popular and stayed around the game much longer than Pinson. After his career ended, Ashburn became a broadcaster for the Phillies and, as such, became even more popular than he was as a player. While he was a good player, he probably never quite reached the level at which a true Hall of Famer needs to perform. As a result, while his 1995 selection by the Veterans Committee was certainly not the worst one it has ever made, it is one that should be looked upon with a great deal of skepticism.

Edd Roush

During his 18-year major league career, Edd Roush played for five different teams, but it was with the Cincinnati Reds that he had his finest seasons. Playing for the Reds from 1916 to 1926, Roush failed to hit over .300 only once. In fact, over that 11-year stretch, he batted at least .321 ten times, surpassing the .340 mark on five different occasions. He won the National League batting title two times, in both 1917 and 1919, with averages of .341 and .321, respectively. He also led the league in triples and doubles once each. Roush batted over .300 thirteen times during his career, stole more than 20 bases six times, and finished in double-digits in triples eleven times. He was the best centerfielder in the National League from 1917 to 1921.

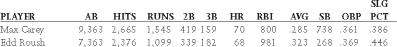

However, at no point during his career was Roush considered to be the best centerfielder in the game, or even among the five best players in his league. The American League’s Ty Cobb and Tris Speaker were always rated well above him and, for much of his career, he was also ranked behind the Pittsburgh Pirates’ Max Carey, who, as we saw earlier, was a borderline Hall of Famer himself. A look at the career numbers of Carey and Roush indicates how tenuous the latter’s status as a legitimate Hall of Famer really is:

Roush compiled a much higher batting average and slugging percentage than Carey. He also drove in more runs, collected more triples, and hit virtually the same number of home runs in 2,000 fewer at-bats. However, Carey’s overall numbers were more impressive. He finished with almost 300 more hits and almost 450 more runs scored than Roush, and he also stole almost three times as many bases. In addition, Carey walked much more frequently than Roush, thereby finishing with an on-base percentage that was nearly as good. As a leadoff hitter, Carey’s primary job was to get on base and score a lot of runs, two things he did very well. Since he was batting at the top of the order, he could not be expected to drive in as many runs as Roush, who usually batted in the middle of his team’s lineup. Therefore, the discrepancy in their RBI totals is really insignificant. Carey was also the better outfielder of the two.

In addition, Roush knocked in as many as 90 runs only once during his career, reaching the 80-mark only two other times. He never scored more than 95 runs in a season, and he scored as many as 80 runs only six times. Having many of his best years during the 1920s at a time when runs were being scored at a record pace, Roush was simply not a big run-producer. While he did hit for some high batting averages during the decade, the figures he posted did not exceed the league norm by enough to compensate for his lack of productivity. When compared to the numbers accumulated by other players of his era who were legitimate Hall of Famers, Roush’s totals pale by comparison. In short, Roush was a good player, but he just did not accomplish enough during his career to merit his 1962 selection by the Veterans Committee.