Banana (12 page)

Authors: Dan Koeppel

22

Brand Name

Bananas

B

ANANA COMPANIES STILL HAD TO SELL BANANAS,

and in a world with thinning supply it was important to each to sell more of

its

own bananas. There were several banana growers, but once the fruit arrived in markets, there was no way to distinguish whether a particular banana came from United Fruit,

*

Standard Fruit, or a smaller rival. The largest banana company's method of increasing sales was to turn the fruit it sold into a brand name. The invention of “Chiquita” involved more than just a simple name. (Initially, the logo was placed on a band that held bunches together. Stickers didn't come until later.)

In 1944 the company introduced the Chiquita banana jingle, arguably the most well-known advertising melody of all time. The tune was written by the banana company's advertising agency and was presented by an animated banana, who sang with an exotic accent and wore a bowl of fruit on her head. Miss Chiquita was patterned after Brazilian bombshell actress Carmen Miranda, who had worn a similar costume while she danced seductively amidst a troupe of man-sized bananas in the 1943 musical film

The Gang's All Here

. Miranda was frequently addressed in her movies with the Spanish diminutive that the banana company adopted. Chiquita's tuneful mascot didn't turn into a “real” woman until a 1967 redesign.

The original Chiquita theme is not the one you hear today. It was performed in a sultry, salsa-influenced style, with lyrics that provided another measure of consumer education:

I'm Chiquita banana and I've come to say

Bananas have to ripen in a certain way

When they are fleck'd with brown and have a golden hue

Bananas taste the best and are best for you

You can put them in a salad

You can put them in a pie-aye

Any way you want to eat them

It's impossible to beat them

But, bananas like the climate of the very, very tropical equator

So you should never put bananas in the refrigerator.

The catchy tune was an instant hit, even if the information it provided was wrongâand a sly way to boost sales: As historian Virginia Scott Jenkins points out, the company that ran dozens of cold-storage rooms across the United States knew that bananas actually last longer when refrigerated.

Today, that little bit of misinformation has been replaced, along with the rest of the song's lyrics.

I'm Chiquita Banana and I've come to say

I offer good nutrition in a simple way

When you eat a Chiquita you've done your part

To give every single day a healthy start

Underneath the crescent yellow

You'll find vitamins and great taste

With no fat, you just can't beat 'em

You'll feel better when you eat 'em

They're a gift from Mother Nature and a natural addition to your table

For wholesome, healthy, pure bananasâlook for Chiquita's label!

The jingle's melody has been rearranged as well. It is far less sexy, less Latin. If the Gros Michel was a banana with spectacular taste and personality, then the new tune is as plainâand ubiquitousâas the Cavendish that would soon replace it.

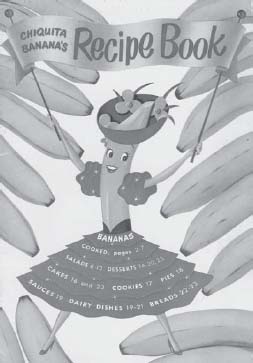

The original sexy singing banana

teaches you to cook (1947).

23

Guatemala

S

AM ZEMURRAY

had retired in 1951, and as with many industrial titans, had turnedâperhaps out of conscienceâto philanthropy. He helped Wilson Popenoe found his Honduran training facility. With his wife, Zemurray funded a women's studies professorship at Harvard. He worked to preserve Mayan ruins throughout Central America (Zemurray's daughter, Doris, was an archaeologist who directed Costa Rica's national museum in the 1960s). The bootstraps immigrant provided cash to support

The Nation

, the weekly liberal newsmagazine.

But Zemurray was not quite a former banana baron. He continued to chair the company's executive committee, and old Samâthe street fighter who, upon taking over United Fruit more than two decades earlier, became known to Wall Street as “the fish that swallowed the whale”âwould emerge one final time.

It was 1954. Guatemala.

The small countryâCentral America's northernmost, sharing a border with Mexicoâwas deeply impoverished, with an average life expectancy of under forty years, and deeply dependent on bananas. More than half of the country's economy was tied to growing, harvesting, and transporting the fruit. Zemurray's company controlled 75 percent of that trade.

Guatemala had been one of the most important centers of the Mayan empire, and most of the country's 3 million people were descended from that culture, which had hidden treasures in sacred caves and filled the jungles with towering, intricately carved pyramids. More than just about any other Latin American nation, Guatemala's native population had suffered since the arrival of the Spanish in the early sixteenth century; for hundreds of years, Mayasâmany of whom spoke no Spanish, using instead one of over twenty native dialectsâhad no civil rights and lived in conditions that were among the most primitive in the Western Hemisphere.

It was a perfect place to grow bananas. United Fruit arrived in the country in the early 1900s, building the town of Bananera near the Caribbean port of Rio Dulce. (Bananera's are among the oldest continually operating plantations in the world, though they were taken over by Del Monte in 1972. That company still both harvests and funds an agricultural research center there.) Part of the country's suitability was its terrain and climate. But even more important was the nation's governmentâor lack of it. The first Guatemalan president to encounter United Fruit was Manuel Estrada Cabrera, who ruled from 1898 through 1920. Estrada believed his country needed to modernize and invited United Fruit to build the nation's entire infrastructure; the banana giant constructed telegraph lines, railroads, and seaports. (The only thing the company didn't build was roads, since highways might be a threat to the train lines that ensured dominance in the banana industry.)

None of these “improvements” benefited the descendants of the Mayas. The country's ruling Ladino classâthose with Spanish lineageâbecame richer; the poor probably didn't get poorer (they were already beyond destitute), but village life declined as the plantations were built. Estrada was a modernizer, but, like most absolute rulersâand he soon became oneâhe also exhibited streaks of imperiousness and ruthlessness. Freedom of the press was abolished. Enemies were executed. The Guatemalan president's most bizarre caprice was his admiration for Minerva, the Roman goddess of wisdom. During his rule, he built, with banana money, several Greco-Roman-style temples to her, including one in Guatemala City with the inscription: “Manuel Estrada Cabrera Presidente de la Republica a la juventud estudiosa” (Manuel Estrada Cabrera, President of the Republic, to studious youths).

Estrada was overthrown in 1920. Five more rulers followed, until 1931, when General Jorge Ubico took office. Ubico had won an election but instantly assumed absolute power, changing the country's laws to give him an unlimited term in office. Ubico's attitudes toward Guatemala's peasants were practically schizophrenic. He nursed the country through the Depression, holding town meetings in the indigenous villages and listening so patiently to complaints that people living in the places he visited began to call him “father.” At the same time, Ubico issued edicts that made him, even today, one of the cruelest rulers in Latin American history; he required most Indians to work for landownersâUnited Fruit owned or controlled the vast majority of Guatemala's cultivated terrainâfor a minimum of one hundred days annually. He created a secret police force. Most notoriously, Ubico passed laws that imposed the harshest penalty on any non-Ladino who failed to follow orders when he was working: The offender could be murdered on the spot.

Like Estrada, Ubico's ego was tied in with his mightâand expressed in bizarre fashion. He imagined that he was the heir, or even the reincarnation, of Napoléon, commissioning paintings and busts of himself for civic buildings and even dressing Guatemalan soldiers in uniforms that resembled those worn by eighteenth-century French troops. He was a believer in numerology: A star with the number five at the center was displayed above the presidential palace on holidays. The pentagram's points and the numeric symbol were representative of the letters in the dictator's first and last names. Tomás Borge MartÃnez, cofounder of the Nicaraguan Sandinista movement, said that the dictator was “crazier than a half-dozen opium smoking frogs.”

Ubico's rule came at the time Panama disease was hitting Guatemala hardest. As the malady spread into the countryside, United Fruit took possession of so much land that many of its tracts were considered nations within a nation. The fruit company was allowed to undervalue the land it owned, and the stated worth of its holdings were so low that it didn't have to pay taxes.

Ubico's biggest enemy was Communism. He “saw Communist conspiracies everywhere,” historians Marcelo Bucheli and Geoffrey Jones observe. In addition to detaining and sometimes killing anyone perceived as having connections with a labor movement, Ubico also bannedâmeaning they couldn't be written or spokenâwords and phrases like

trade union

,

strike

, and

petition

. Ubico's attempt to control his nation's vocabulary climaxed when he banned the word

workers

. From that point on, whether you were a street sweeper or a banana picker, you were to be calledâand only calledâan

employee

.

Guatemala, wrote the

New York Times

, was a “big, private madhouse.” The residents of that madhouse were a banana company desperate for new land, a dictator who opposed any form of organization for impoverished workers, and a world that, by 1944, was quickly polarizing into West and East, capitalist and Communist, American and Soviet. Guatemala was about to explode.

IF THE COUNTRY WAS A TIME BOMB

,

the fuse was lit in an unexpected way. Since Ubico took power, a new group had emerged in Guatemala: a middle class. Though they had comfortable lives, they resented the fact that their nation was, in most respects, little more than a giant, foreign-owned banana plantation. The first strikes began with schoolteachers. Throughout 1944, more and more ordinary Guatemalans filled the streets of their cities despite Ubico's attempts to banish even the language of rebellion from his citizens' minds. The government response was typical. Soldiers were called in, and the demonstrators were fired upon. But this timeâin a world that was successfully beating back the forces of fascismâthe violence turned into a catalyst: The strikes and protests expanded. In July, Ubico attempted to maintain his grip by “resigning,” naming a loyal crony as his successor. The puppet regime was forced to call for elections but held on to power by jailing opposition candidates and reserving control over the military. As long as it maintained that grip, Ubico and his allies would remain in power, and Guatemala would remain a banana republic.

THE GUATEMALAN GENERALS DIDN'T CRUMBLE

.

They succumbed to a surprise attack. The army's junior officers had been discontented since late June, when forces loyal to Ubico fired on protesters in Guatemala City, killing MarÃa Chinchilla, a grade school teacher. The battle began in October, at Fort Matamorosâthe headquarters of the nation's military, located at the geographic center of Guatemala City. A pair of young soldiers, Captain Jacobo Arbenz (a former schoolteacher) and Major Francisco Arana, spear-headed the effort. Seventy students were surreptitiously brought into the military base. Within minutes, they'd killed the high-ranking officers who supported the government and gained control of much of the base's heavy artillery. A battle between loyalists and the rebelling soldiers and students ensued; twelve hours later, Fort Matamoros had been completely destroyed, 1,800 loyalists and rebels were dead, and the government had fallen. Ubico's hand-picked replacement, General Francisco Ponce, resigned. He left, along with his patron, for exile in Mexico. Arbenz and Arana quickly called for elections; a university professor named Juan José Arévalo gained the presidency in 1945. It was the beginning of what Guatemalans call Los Diez Años de la Primavera, “The Ten Years of Springtime.”

Despite Arévalo's reformsâhe allowed political parties and press freedom, and for the first time term limits were imposed on elected officials, including the presidentâthe lives of banana workers changed little. United Fruit controlled the countryside, and changes in labor practices, such as the legalization of trade unions, specifically excluded those working on plantations. Arévalo attempted to improve living standards nationwide by building schools, hospitals, and enacting social welfare programs. He had already attracted the suspicious attention of the United States by describing himself as a “spiritual socialist,” which meant that he hoped to liberate the minds of the peasants, even if their physical lives were still, for the moment, tightly controlled by outside interests. It hardly mattered that Arévalo also listed his idols as Abraham Lincoln and FDR.

The Arévalo regime came under near-constant attack. Arbenz helped put down a coup against the leader in 1949, and, facing constant oppositionâover two dozen plots against Arévalo were foiledâthe president's term expired without major land reform. That left Guatemala's big problem unsolved, according to Stephen Kinzer and Stephen Schlesinger, authors of

Bitter Fruit: The Story of the American Coup in Guatemala

.

In 1950 Arévalo was the first president of Guatemala ever to finish a termâand leave, as the law dictated. Though he was viewed as a hero by the Guatemalan people, his own self-critique was more pessimistic: “When I ascended to the presidency of the nation,” he said, “I was possessed by a romantic fireâ¦I still believedâ¦that the government of Guatemala could rule itself, without submission to external forces.” He blamed his disappointment directly on United Fruit and the United States: “The banana magnates, co-nationals of Roosevelt, rebelled against the audacity of a Central American president who gave his fellow citizens a legal equality with the honorable families of exporters.”

Whatever Arévalo couldn't, or didn't, accomplish was left to his successor, Jacobo Arbenz. The former junior officer would go on to become the biggest enemy in United Fruit's history.

What bothered Arbenz most wasn't even that the banana companies owned so much land in the countryâ4 million acres, or 70 percent of the nation's arable territoryâbut that they weren't using it. More than three-fourths of it was fallow. In his inaugural speech, Arbenz, according to Kinzer and Schlesinger, said he wanted to convert Guatemala from a “dependent nation with a semi-colonial economy to an economically independent country.” The new president had been warned to temper his remarks, so he chose not to mention specific targets by name when he called for land reform, saying only that his goal was only to rid the nation of its

latifundios

.

The term means “private farms.” Nobody could mistake who the thirty-eight-year-old president was talking about.

THERE WERE COMMUNISTS IN GUATEMALA

.

The party was active, and Arbenz saw them as part of his coalition. Many of the country's workers supported the party. Arbenz was eager to listen to their ideas. Some party members were appointed to cabinet posts. Arbenz knew that he had to rule by coalition, and though he saw the party as a valuable allyâand even had Communist advisors as he planned land reformâhis partner in rebellion, Francisco Arana, maintained control over the military, where there were no Communist influences, and expanded the press freedoms originally enacted by Arévalo. Arbenz may not have possessed entirely clean hands. Arana was murdered in 1949. The theory, never confirmed and often disputed, is that Arbenz, frustrated by his compatriot's failure to fully support the new policies, engineered the killing.

IN OCTOBER 1951

,

Arbenz had his first hostile encounter with United Fruit. A company official had arrived at the presidential palace with a series of dictates: The banana giant's current contracts would be extended. Taxes would not be raised. As Sam Zemurray had once done from the other side of the table, Arbenz, according to Schlesinger and Kinzer, “repliedâ¦in a manner to which the Boston executive was not accustomed.” The Guatemalan asked for payment of export duties; he asked that the company offer fair prices for land it acquired; and, most audaciously, he asked that United Fruit obey the Guatemalan constitution.