Bad Science (27 page)

Authors: Ben Goldacre

Tags: #General, #Life Sciences, #Health & Fitness, #Errors, #Health Care Issues, #Essays, #Scientific, #Science

Though mumps is rarely fatal, it’s an unpleasant disease with unpleasant complications (including meningitis, pancreatitis, and sterility). Congenital rubella syndrome has become increasingly rare since the introduction of MMR but causes profound disabilities, including deafness, autism, blindness, and mental handicap, resulting from damage to the fetus during early pregnancy.

The other thing you will hear a lot is that vaccines don’t make much difference anyway, because all the advances in health and life expectancy have been due to improvements in public health for a wide range of other reasons. As someone with a particular interest in epidemiology and public health, I find this suggestion flattering, and there is absolutely no doubt that deaths from measles began to fall over the whole of the past century for all kinds of reasons, many of them social and political as well as medical: better nutrition, better access to good medical care, antibiotics, less crowded living conditions, improved sanitation, and so on.

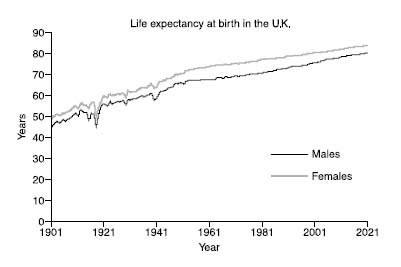

Life expectancy in general has soared over the past century, and it’s easy to forget just how phenomenal this change has been. In 1901, males born in the U.K. could expect to live to forty-five, and females to forty-nine. By 2004, life expectancy at birth had risen to seventy-seven for men and eighty-one for women (although of course, much of the change is due to reductions in infant mortality).

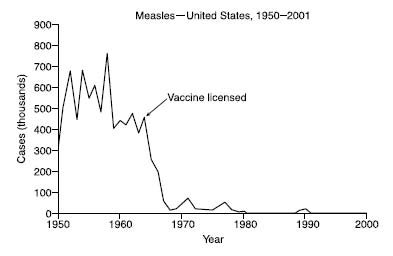

So we are living longer, and vaccines are clearly not the only reason why. No single change is the reason why. Measles incidence dropped hugely over the preceding century, but you would have to work fairly hard to persuade yourself that vaccines had no impact on that. Here, for example, is a graph showing the reported incidence of measles from 1950 to 2000 in the United States.

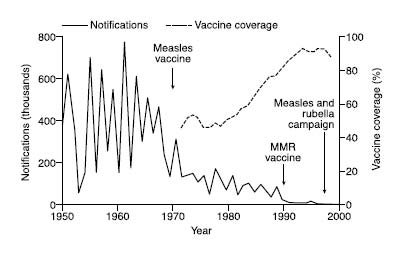

For those who think that single vaccines for the components of MMR are a good idea, you’ll notice that these have been around since the 1970s, but that a concerted program of vaccination, and the concerted program of giving all three vaccinations in one go as MMR, are fairly clearly associated in time with a further (and actually rather definitive) drop in the rate of measles cases.

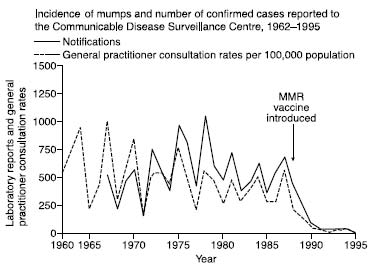

The same is true for mumps.

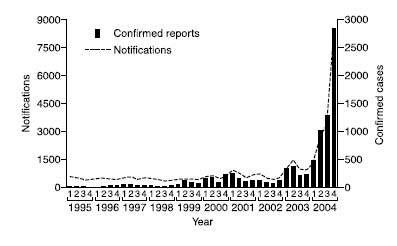

While we’re thinking about mumps, let’s not forget our epidemic in 2005, a resurgence of a disease that many young doctors would struggle even to recognize. Here is a graph of mumps cases from the

BMJ

article that analyzed the outbreak:

Almost all confirmed cases during this outbreak were in people aged fifteen to twenty-four, and only 3.3 percent had received the full two doses of MMR vaccine. Why did it affect these people? Because of a global vaccine shortage in the early 1990s.

Mumps is not a harmless disease. I’ve no desire to scare anyone—and as I said, your beliefs and decisions about vaccines are your business; I’m interested only in how you came to be so incredibly misled—but before the introduction of MMR, mumps was the commonest cause of viral meningitis and one of the leading causes of hearing loss in children. Lumbar puncture studies show that around half of all mumps infections involve the central nervous system. Mumps orchitis is common, exquisitely painful, and occurs in 20 percent of adult men with mumps; around half will experience testicular atrophy, normally in only one testicle, but 15 to 30 percent of patients with mumps orchitis will have it in both testicles, and of these, 13 percent will have reduced fertility.

I’m not just spelling this out for the benefit of the lay reader; by the time of the outbreak in 2005, young doctors needed to be reminded of the symptoms and signs of mumps, because it had been such an uncommon disease during their training and clinical experience. People had forgotten what these diseases looked like, and in that regard vaccines are a victim of their own success, as we saw in our earlier

quote

from

Scientific American

in 1888, five generations ago.

Whenever we take a child to be vaccinated, we’re aware that we are striking a balance between benefit and harm, as with any medical intervention. I don’t think vaccination is all that important: even if mumps orchitis, infertility, deafness, death, and the rest are no fun, the sky wouldn’t fall in without MMR. But taken on their own, lots of other individual risk factors aren’t very important either, and that’s no reason to abandon all hope of trying to do something simple, sensible, and proportionate about them, gradually increasing the health of the nation, along with all the other stuff you can do to the same end.

It’s also a question of consistency. At the risk of initiating mass panic, I feel duty bound to point out that if MMR still scares you, then so should everything in medicine and indeed many of the everyday lifestyle risk exposures you encounter, because there are a huge number of things that are far less well researched, with a far lower level of certainty about their safety. The question would still remain of why you were so focused on MMR. If you wanted to do something constructive about this problem, instead of running a single-issue campaign about MMR, you might, perhaps, use your energies more usefully. You could start a campaign for constant automated vigilance of the entirety of the Food and Drug Administration data set for any adverse outcomes associated with any intervention, for example, and I’d be tempted to join you on the barricades.

But in many respects this isn’t about risk management or vigilance; it’s about culture, human stories, and everyday human harms. Just as autism is a peculiarly fascinating condition to journalists, and indeed to all of us, vaccination is similarly inviting as a focus for our concerns. It’s a universal program, in conflict with modern ideas of “individualized care” it’s bound up with government; it involves needles going into children; and it offers the opportunity to blame someone, or something, for a dreadful tragedy.

Just as the causes of these scares have been more emotional than anything else, so too has much of the harm. Parents of children with autism have been racked with guilt, doubt, and endless self-recrimination over the thought that they themselves are responsible for inflicting harm upon their own children. This distress has been demonstrated in countless studies: but so close to the end, I don’t want to introduce any more research papers.

There is one quote that I find, although she would perhaps complain about my using it, both moving and upsetting. It’s from Karen Prosser, who featured with her autistic son Ryan in the Andrew Wakefield video news release from the Royal Free Hospital in 1998. “Any mother who has a child wants it to be normal,” she says. “To then find out your child might be genetically autistic is tragic. To find out that it was caused by a vaccine, that you agreed to have done…is just devastating.”

I could go on. As I write this, the media are still pushing a celebrity-endorsed “miracle cure” (and I quote) for dyslexia, invented by a millionaire paint entrepreneur, despite the abysmal evidence to support it, and despite customers’ being at risk of simply losing their money anyway, because the company seems to be going into administration; more “hidden data” scandals are exposed from the vaults of big pharma every month; quacks and cranks continue to parade themselves on television, quoting fantastical studies to universal approbation; and there will always be new scares, because they sell so very well, and they make journalists feel alive.

To anyone who feels their ideas have been challenged by this book or who has been made angry by it—to the people who feature in it, I suppose—I would say this: you win. You really do. I would hope there might be room for you to reconsider, to change your stance in the light of what might be new information (as I will happily do, if there is ever an opportunity to update this book). But you will not need to because, as we both know, you collectively have almost full-spectrum dominance. Your ideas—bogus though they may be—have immense superficial plausibility, they can be expressed rapidly, they are endlessly repeated, and they are believed by enough people for you to make very comfortable livings and to have enormous cultural influence. You win.

It’s not the spectacular individual stories that are the problem so much as the constant daily grind of stupid little ones. This will not end, and so I will now abuse my position by telling you, very briefly, exactly what I think is wrong and some of what can be done to fix it.

The process of obtaining and interpreting evidence isn’t taught in schools, nor are the basics of evidence-based medicine and epidemiology, yet these are obviously the scientific issues that are most on people’s minds. Science coverage now tends to come from the world of medicine, and the stories are of what will kill you, or save you. Perhaps it is narcissism, or fear, but the science of health is important to people, and at the very time when we need it the most, our ability to think around the issue is being energetically distorted by the media, corporate lobbies, and, frankly, cranks.

Without anybody’s noticing, bullshit has become an extremely important public health issue, and for reasons that go far beyond the obvious hysteria around immediate harms, the odd measles tragedy or a homeopath’s unnecessary malaria case. Doctors today are keen—as it said in our medical school notes—to work “collaboratively with the patient toward an optimum health outcome.” They discuss evidence with their patients, so that they can make their own decisions about treatments.

In my job as a doctor I meet patients from every conceivable walk of life, in huge numbers, discussing some of the most important issues in their lives. This has consistently taught me one thing: people aren’t stupid. Anybody can understand anything, as long as it is clearly explained, but, more than that, if they are sufficiently interested. What determines an audience’s understanding is not so much scientific knowledge as motivation: patients who are ill, with an important decision to make about treatment, can be very motivated indeed.

But journalists and miracle cure merchants sabotage this process of shared decision making, diligently, brick by brick, making lengthy and bogus criticisms of the process of systematic review (because they don’t like the findings of just one), extrapolating from lab dish data, misrepresenting the sense and value of trials, carefully and collectively undermining people’s understanding of the very notion of what it means for there to be evidence for an activity. In this regard they are, to my mind, guilty of an unforgivable crime.

You’ll notice, I hope, that I’m more interested in the cultural impact of nonsense—the medicalization of everyday life, the undermining of sense—and in general I blame systems more than particular people. While I do go through the backgrounds of some individuals, this is largely to illustrate the extent to which they have been misrepresented by the media, who are so desperate to present their favored authority figures as somehow mainstream. I am not surprised that there are individual entrepreneurs, but I am unimpressed that the media carry their assertions as true. I am not surprised that there are people with odd ideas about medicine or that they sell those ideas. But I am spectacularly, supremely, incandescently unimpressed when a university starts to offer B.Sc. science courses in them. I do not blame individual journalists (for the most part), but I do blame whole systems of editors and the people who buy newspapers with values they profess to despise.

Similarly, while I could reel out a few stories of alternative therapists’ customers who’ve died unnecessarily, it seems to me that people who choose to see alternative therapists (except for nutrition therapists, who have worked

very

hard to confuse the public and to brand themselves as conventional evidence-based practitioners) make that choice with their eyes open or at least only half closed. To me this is not a situation of businesspeople exploiting the vulnerable, but rather, as I seem to keep saying, a bit more complicated than that. We love this stuff, and we love it for some fascinating reasons, which we could ideally spend a lot more time thinking and talking about.

Economists and doctors talk about “opportunity costs,” the things you could have done but didn’t, because you were distracted by doing something less useful. To my mind, the greatest harm posed by the avalanche of nonsense we have seen in this book is best conceived of as the “opportunity cost of bullshit.”

We have somehow become collectively obsessed with these absurd, thinly evidenced individual tinkerings in diet, distracting us from simple, healthy eating advice but, more than that, as we saw, distracting us from the other important lifestyle risk factors for ill health that cannot be sold or commodified.

Doctors, similarly, have been captivated by the commercial success of alternative therapists. They could learn from the best of the research into the placebo effect and the meaning response in healing, and apply that to everyday clinical practice, augmenting treatments that are in themselves also effective; instead there is a fashion among huge numbers of them to indulge childish fantasies about magic pills, massages, or needles. That is not forward-looking or inclusive, and it does nothing about the untherapeutic nature of rushed consultations in decaying buildings. It also requires, frequently, that you lie to patients. “The true cost of something,” as

The Economist

says, “is what you give up to get it.”

On a larger scale, many people are angry about the evils of the pharmaceutical industry and nervous about the role of profit in health care; but these are formless and uncalibrated intuitions, so the valuable political energy that comes from this outrage is funneled—wasted—through infantile issues like the miraculous properties of vitamin pills or the evils of MMR. Just because big pharma can behave badly, that does not mean that sugar pills work better than placebo, nor does it mean that MMR causes autism. Whatever the wealthy pill peddlers try to tell you, with their brand-building conspiracy theories, big pharma isn’t

afraid

of the food supplement pill industry; it

is

the food supplement pill industry. Similarly, big pharma isn’t frightened for its profits because popular opinion turned against MMR: if they have any sense, these companies are relieved that the public is obsessed with MMR and thus distracted from the other far more complex and real issues connected with the pharmaceutical business and its inadequate regulation.

To engage meaningfully in a political process of managing the evils of big pharma, we need to understand a little about the business of evidence; only then can we understand why transparency is so important in pharmaceutical research, for example, or the details of how it can be made to work or concoct new and imaginative solutions.

But the greatest opportunity cost comes, of course, in the media, who have failed science so spectacularly, getting stuff wrong and dumbing down. No amount of training will ever improve the wildly inaccurate stories, because newspapers already have specialist health and science correspondents who understand science. Editors will always—cynically—sideline those people and give stupid stories to generalists, for the simple reason that they want stupid stories. Science is beyond their intellectual horizon, so they assume you can just make it up anyway. In an era when mainstream media are in fear for their lives, their claims to act as effective gate-keepers to information are somewhat undermined by the content of pretty much every column or blog entry I’ve ever written.

To academics, and scientists of all shades, I would say this: you cannot ever possibly prevent newspapers from printing nonsense, but you can add your own sense into the mix. E-mail the features desk, ring the health desk (you can find the switchboard number on the letters page of any newspaper), and offer them a piece on something interesting from your field. They’ll turn you down. Try again. You can also toe the line by not writing stupid press releases (there are extensive guidelines for communicating with the media online), by being clear about what’s speculation in your discussions, by presenting risk data as “natural frequencies,” and so on. If you feel your work—or even your field—has been misrepresented, then complain. Write to the editor, the journalist, the letters page, the readers’ editor, start a blog, put out a press release explaining why the story was stupid; get your press office to harass the paper or TV station, use your title (it’s embarrassing how easy they are to impress), and offer to write them something yourself.

The greatest problem of all is dumbing down. Everything in the media is robbed of any scientific meat, in a desperate bid to seduce an imaginary mass that aren’t interested. And why should they be? Meanwhile, the nerds, the people who studied biochemistry but now work in middle management, are neglected, unstimulated, abandoned. There are intelligent people out there who want to be pushed, to keep their knowledge and passion for science alive, and neglecting them comes at a serious cost to society. Institutions have failed in this regard. The indulgent and well-financed “public engagement with science” community has been worse than useless, because it too is obsessed with taking the message to everyone, rarely offering stimulating content to the people who are already interested.

Now you don’t need these people. Start a blog. Not everyone will care, but some will, and they will find your work. Unmediated access to niche expertise is the future, and you know, science isn’t hard—academics around the world explain hugely complicated ideas to ignorant eighteen-year-olds every September—it just requires motivation. I give you the CERN podcast, the Science in the City mp3 lecture series, blogs from profs, open-access academic journal articles from PLOS, online video archives of popular lectures, the free editions of the Royal Statistical Society’s magazine

Significance

, and many more, all out there, waiting for you to join them. There’s no money in it, but you knew that when you started on this path. You will do it because you know that knowledge is beautiful, and because if only a hundred people share your passion, that is enough.